US stock futures dip as Trump’s firing of Cook sparks Fed independence fears

By Geoffrey Smith

Investing.com -- Fears of a recession are growing across the developed economic world. The risks vary from one country to another, but one set of countries clearly has a tougher time ahead than most others.

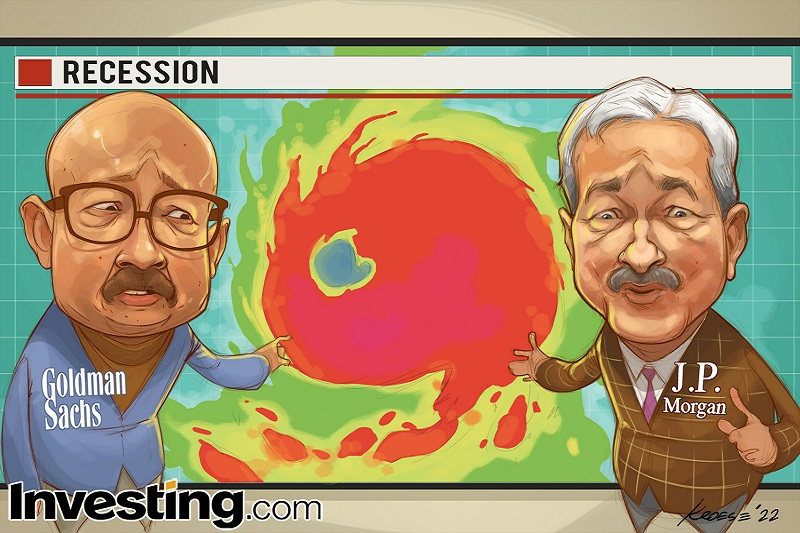

Spoiler: despite Jamie Dimon’s ‘hurricane’ references and Elon Musk’s ‘super bad feeling’ about the economy, it isn’t the U.S. that’s in the most trouble.

The two doyens of U.S. capitalism both sent shivers through financial markets last week with their respective comments, for good reason. Dimon, as chief executive of the country’s biggest bank, has better access to data on the health of American households and businesses than perhaps any other person in the country.

"That hurricane is right out there down the road coming our way," Dimon told an investment conference, adding that it was hard to tell whether it was “a minor one or Superstorm Sandy,” the storm that lashed New York in 2012.

“You better brace yourself," he summed up, after reminding his audience that JPMorgan (NYSE:JPM) was preparing for a “non-benign environment” and “bad outcomes”. Translated into plain English, that means a big step up in provisions against loan losses in the second-quarter results, and a sharp drop in commissions from new loans as demand for home and car credit is crushed by higher interest rates.

Former Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) CEO Lloyd Blankfein had been equally gloomy last month, telling CBS's Face the Nation that the chance of a recession had markedly increased, as central banks hurriedly withdraw the excessive stimulus policies put in place to support the economy through the pandemic.

Dimon is fond of hedging his disaster predictions and points regularly to the strength of household balance sheets as one reason why the U.S. should not be heading into recession now. U.S. household debt, measured against GDP, has fallen from nearly 100% in 2008 to under 80% as of late last year. (Curiously, his chief economist is more relaxed, saying a recession in the U.S. at least isn't "imminent".)

However, that only tells half the story. Data from the Bank for International Settlements suggest that U.S. corporates are heading into the rising interest rate cycle far more levered than before, the result of a decade in which debt finance has been consistently cheaper to raise than equity. Corporate debt, which stood at less than 66% of GDP 10 years ago, stands at over 81%.

Federal debt has, of course, also climbed relentlessly over the last decade due to sustained budget deficits. That suggests a much greater danger to growth if interest rates continue to rise in line with the Federal Reserve’s guidance.

Further afield, the vulnerability to recession is arguably even greater, especially in Europe, where the political imperative to punish Russia for its invasion of Ukraine has generated an essentially artificial – but nonetheless acute – squeeze on energy prices that is now rapidly spreading throughout the economy. The Bank of England has already predicted the U.K. economy will contract when the next rise in regulated energy bills hits the doormats in October. The European Central Bank, meanwhile, will announce a fresh set of economic forecasts at its meeting this Thursday that are sure to show a big downward revision to growth for the year.

Then there is China, another country struggling with a shock that is, if not artificial, has a large man-made component to it. China’s services and manufacturing PMIs have spent most of the last three months in contractionary territory due to lockdowns that have tried to spare factory output but made no concession to consumers. While Shanghai and now Beijing are starting to reopen for business, the authorities have made it clear that any further outbreaks – perhaps from newer and still more transmissible variants of Covid-19 – will be met with exactly the same zero-tolerance response.

However, the countries most at risk are - as ever - those that depend on others for their food and energy supplies. With Crude Oil at $120 a barrel, it hurts to be a net importer like Turkey or Sri Lanka, especially if international tourism is still not generating the money it did before the pandemic. For countries such as Pakistan, Egypt and Tunisia, which depend on Russia and Ukraine for their grain imports as well as being net oil importers, the strain is even greater.

It may be too much to talk of a global recession – things rarely go so badly around the whole world for that to happen – but the likelihood of individual countries, or groups of countries with specific risk profiles, going into recession has risen sharply.

“Even if a global recession is averted, the pain of stagflation could persist for several years,” the World Bank warned on Tuesday, as it published yet another downgrade to its 2022 growth forecasts. According to the bank, the global inflation problem is so widespread that the real per capita income of 40% of people in developing countries will be below pre-Covid levels this year.

The worst may yet be avoided, but ‘super bad feelings’ about the economy are likely to hang around for some time yet.