Raymond James initiates QXO stock with Outperform rating on acquisition strategy

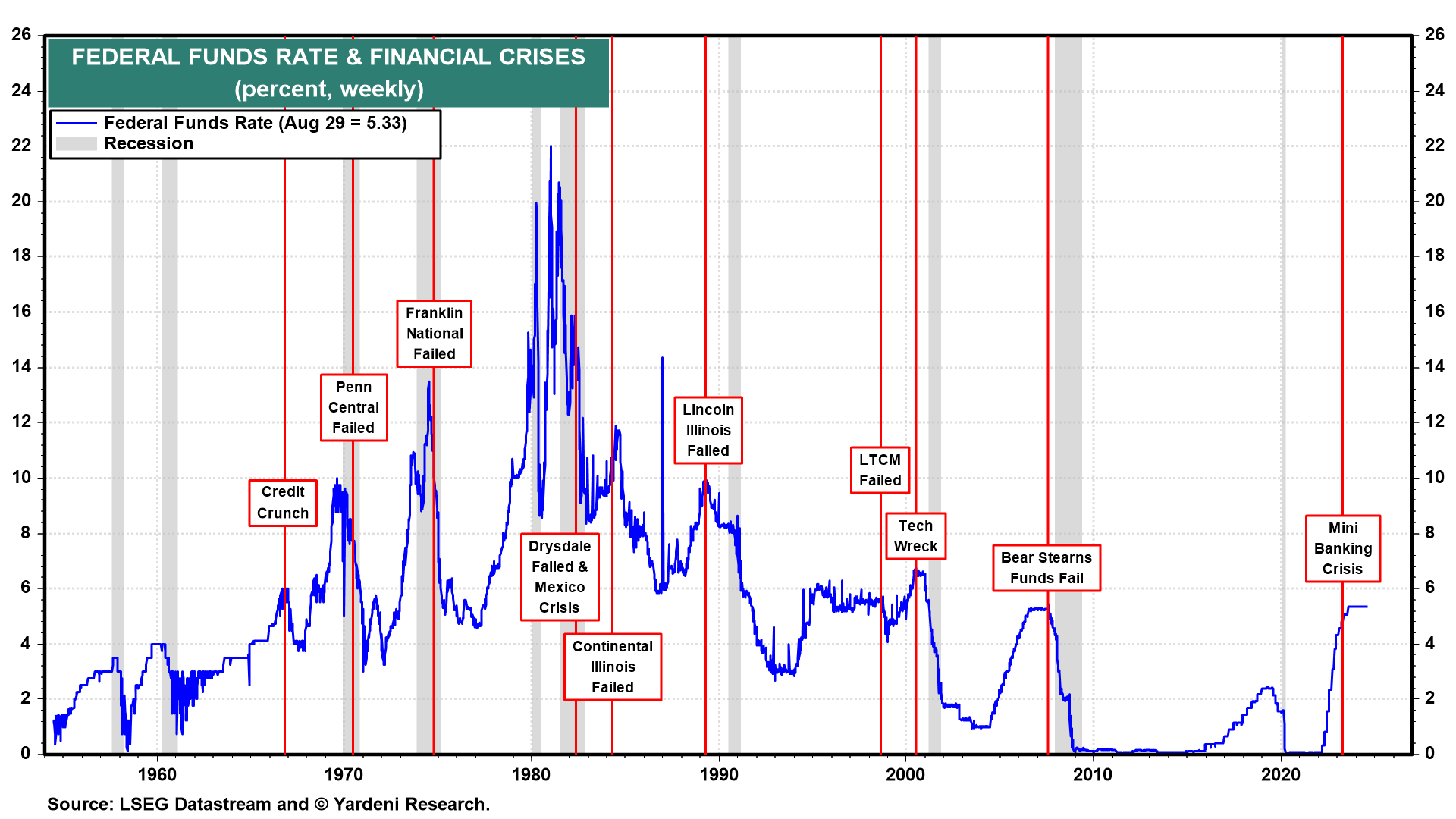

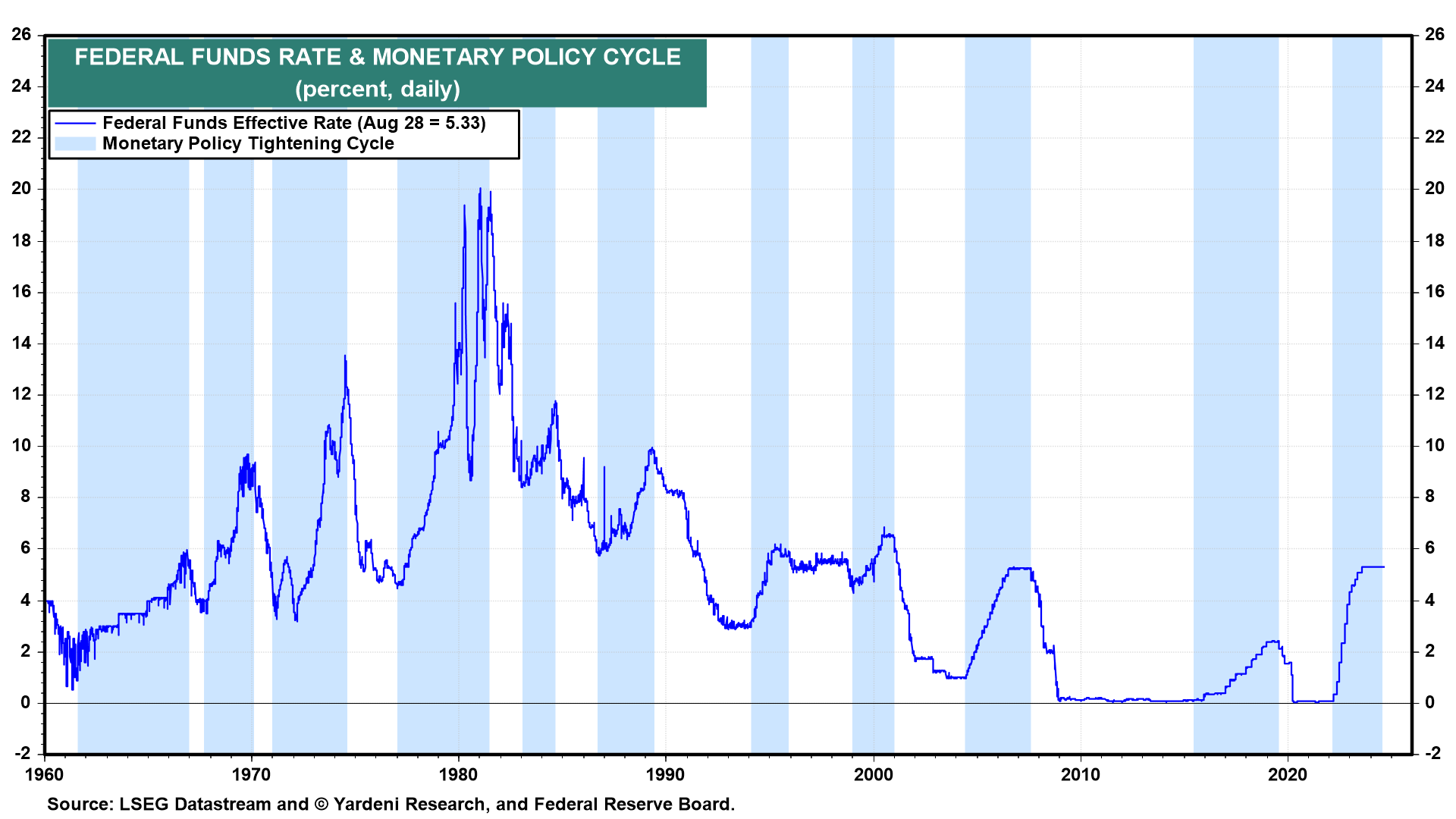

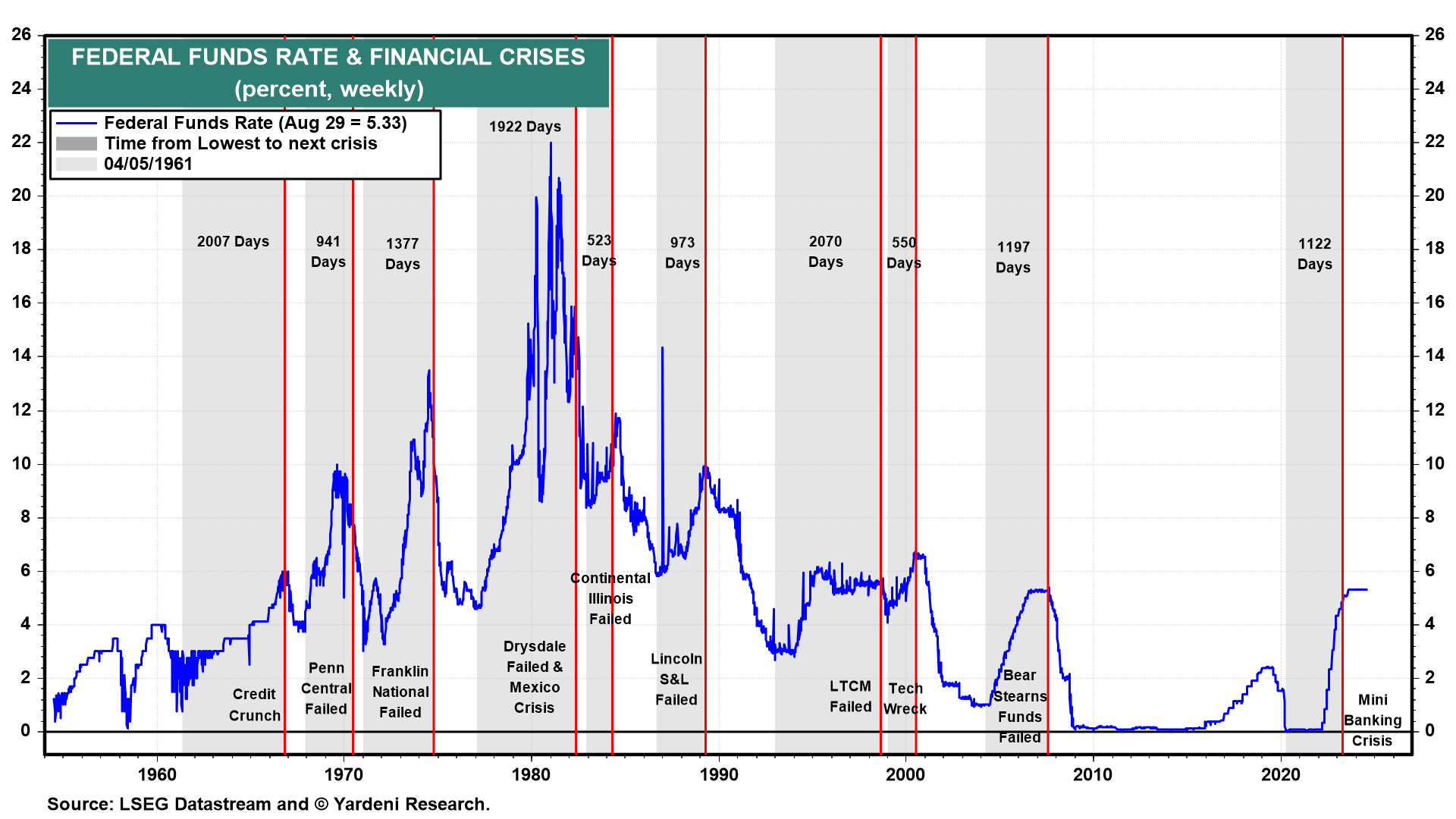

Recessions don’t happen very often, and they don’t last very long. Most of the nine recessions since 1960 were caused by the tightening of monetary policy, which triggered a financial crisis and a credit crunch that caused a recession.

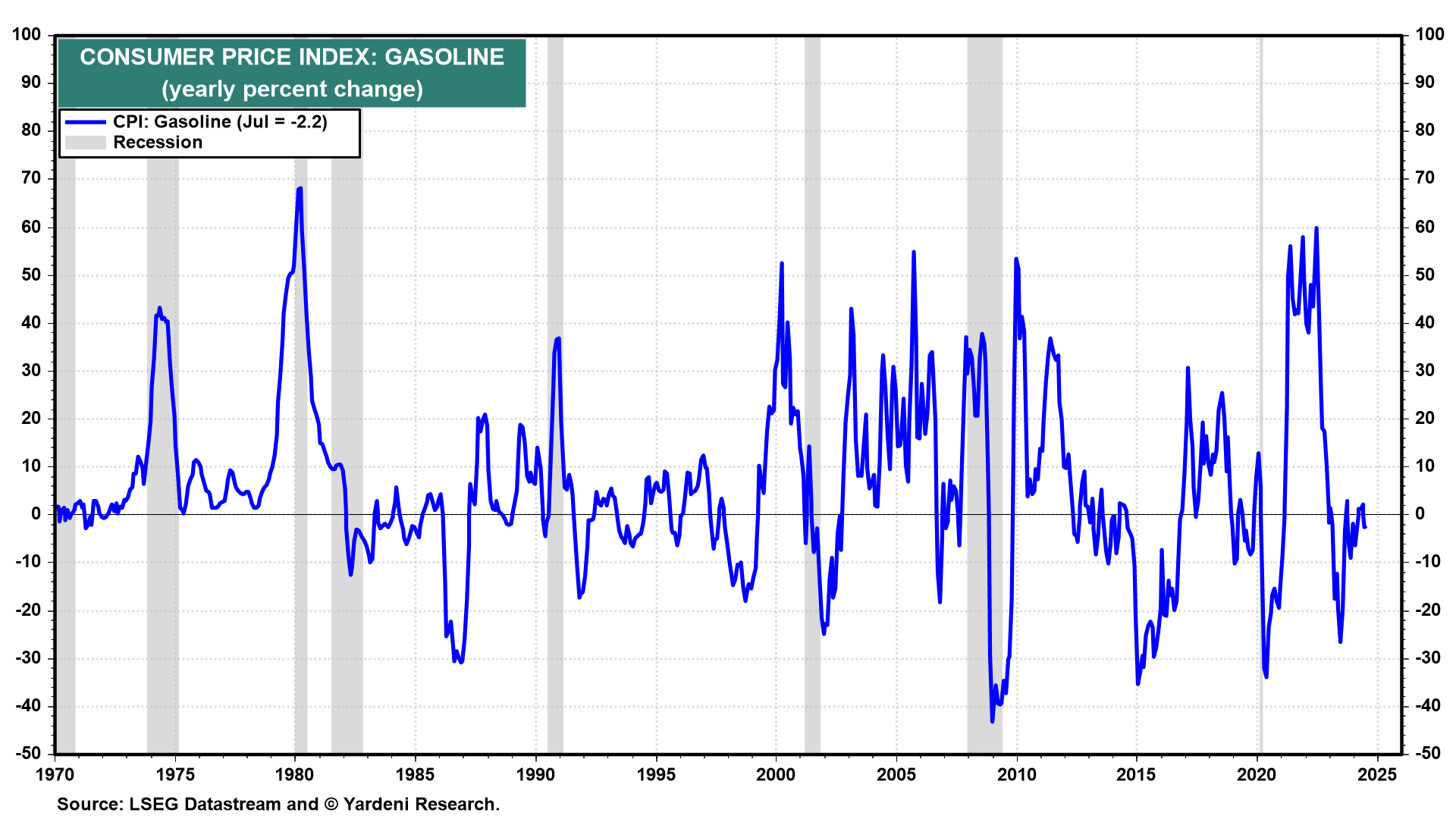

On four occasions since then, the recessions were precipitated or exacerbated by an energy crisis, which caused the prices of crude oil and gasoline to spike. On a few occasions, the recessions resulted from the bursting of speculative bubbles.

The Fed almost always responded immediately to previous financial crises by lowering the federal funds rate significantly.

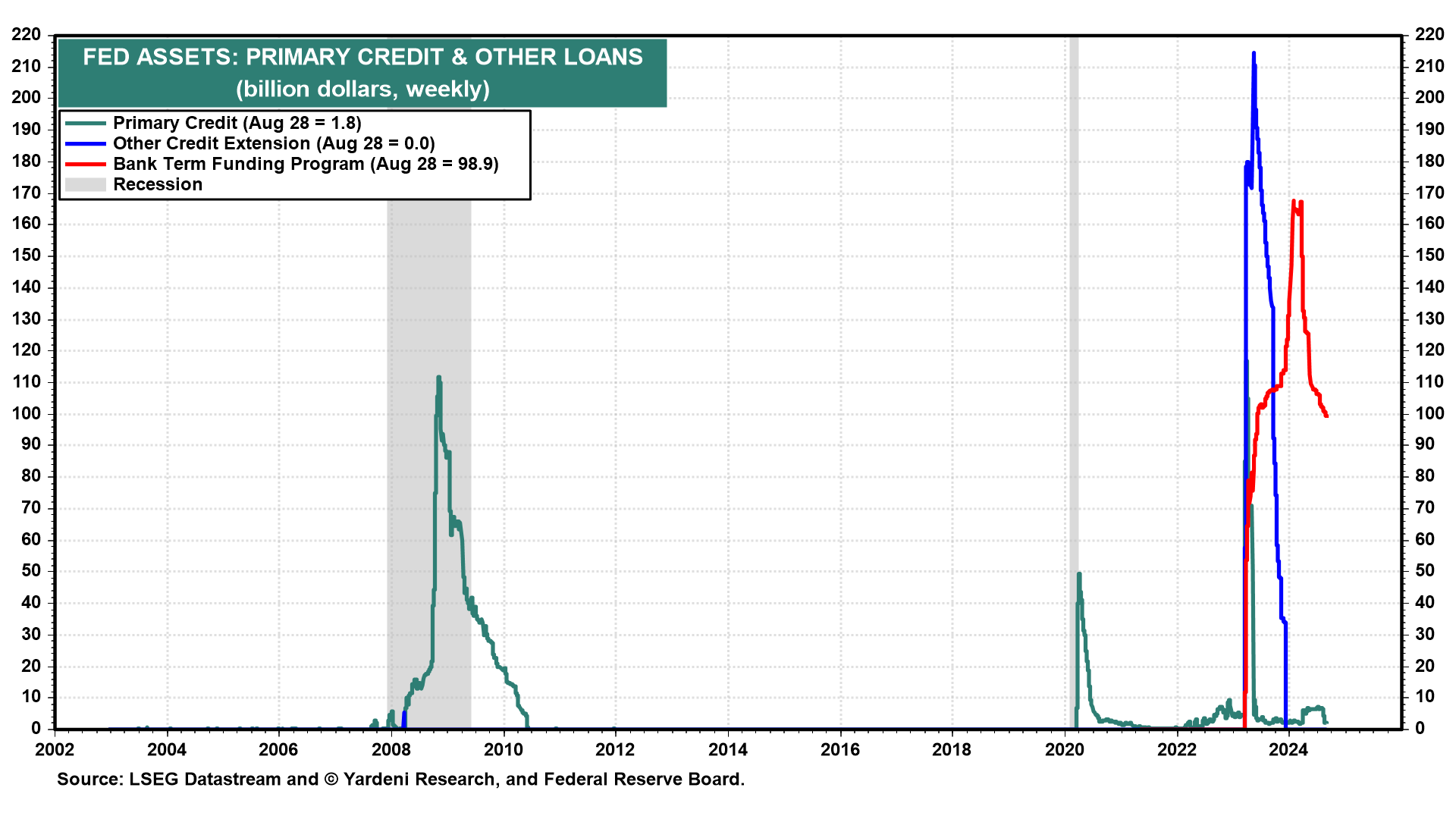

That helped to mitigate the credit crunch and shorten the recession. The one exception occurred in 2023 when the Fed responded to the March banking crisis by rapidly creating an emergency bank liquidity facility.

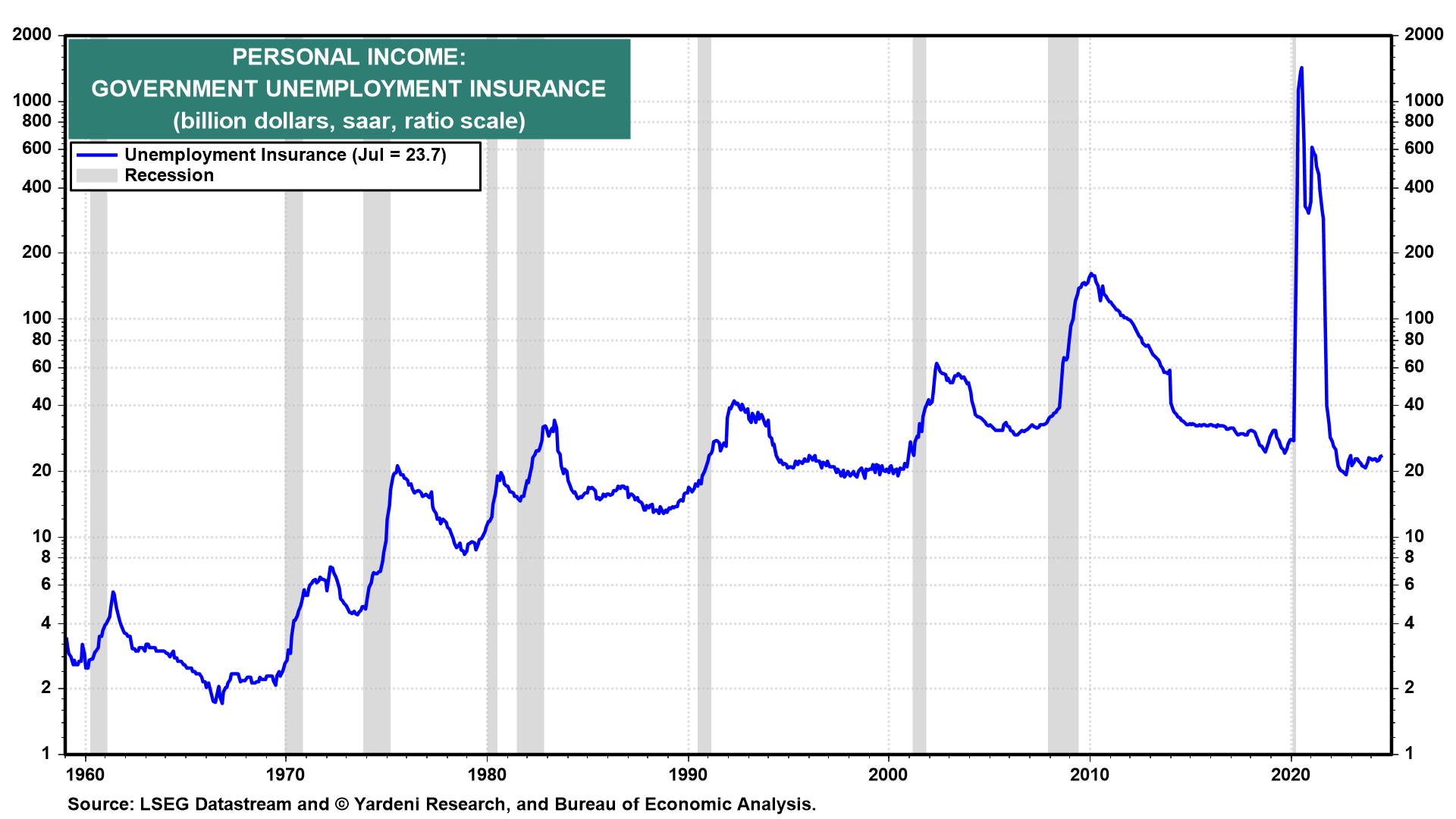

Of course, automatic fiscal stabilizers kicked in, providing income support through the unemployment insurance system.

That helped to moderate the downturns. Activist fiscal policy was usually late to the game, providing tax cuts and other stimulative measures that mostly helped to boost the recovery.

This time has been different so far, we have observed on numerous occasions since early 2022:

1. Normalizing vs tightening monetary policy

The tightening of monetary policy during 2022 and 2023 raised the federal funds rate by 525bps. That was certainly among one of the biggest increases in this rate during monetary policy tightening cycles in history. However, the federal funds rate was raised from zero. So we’ve characterized some of the increase in the federal funds rate as normalizing rather than tightening monetary policy.

2. Fed’s liquidity facilities

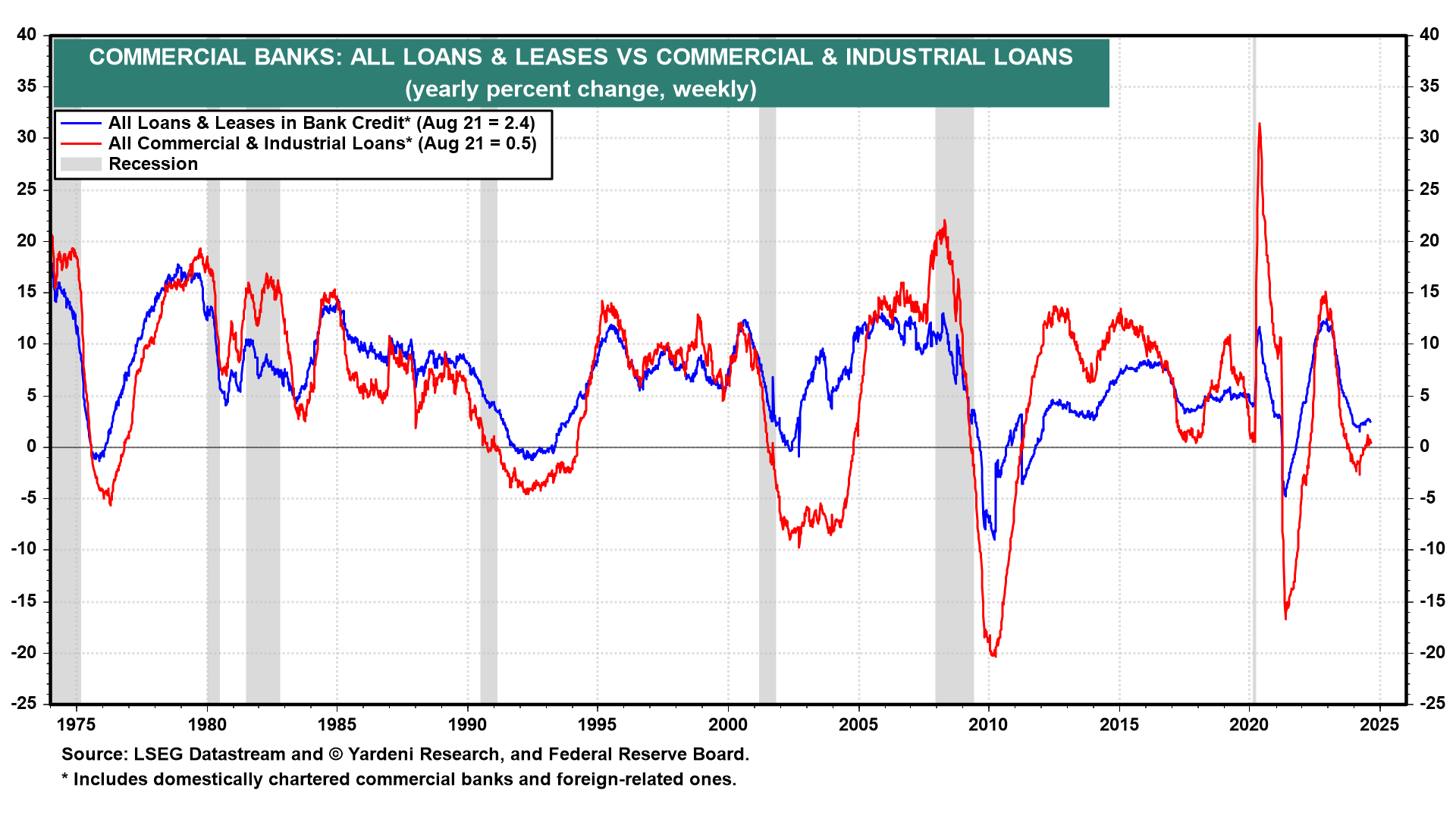

As noted above, there was a mini-banking crisis last year. But thanks to the Fed’s liquidity facility, there has been no credit crunch and no recession. The Fed played Whac-a-Mole during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) and again during the Great Virus Crisis (GVC), learning to stabilize the credit system rapidly by creating emergency liquidity facilities. The difference last year was that the Fed didn’t also lower the federal funds rate as it did during the GFC and GVC.

3. No need to cut the FFR often and rapidly

Therefore, it is very unlikely that the Fed will have to lower the federal funds rate as rapidly and by as much as was necessary during previous monetary easing cycles when financial crises triggered credit crunches and recessions.

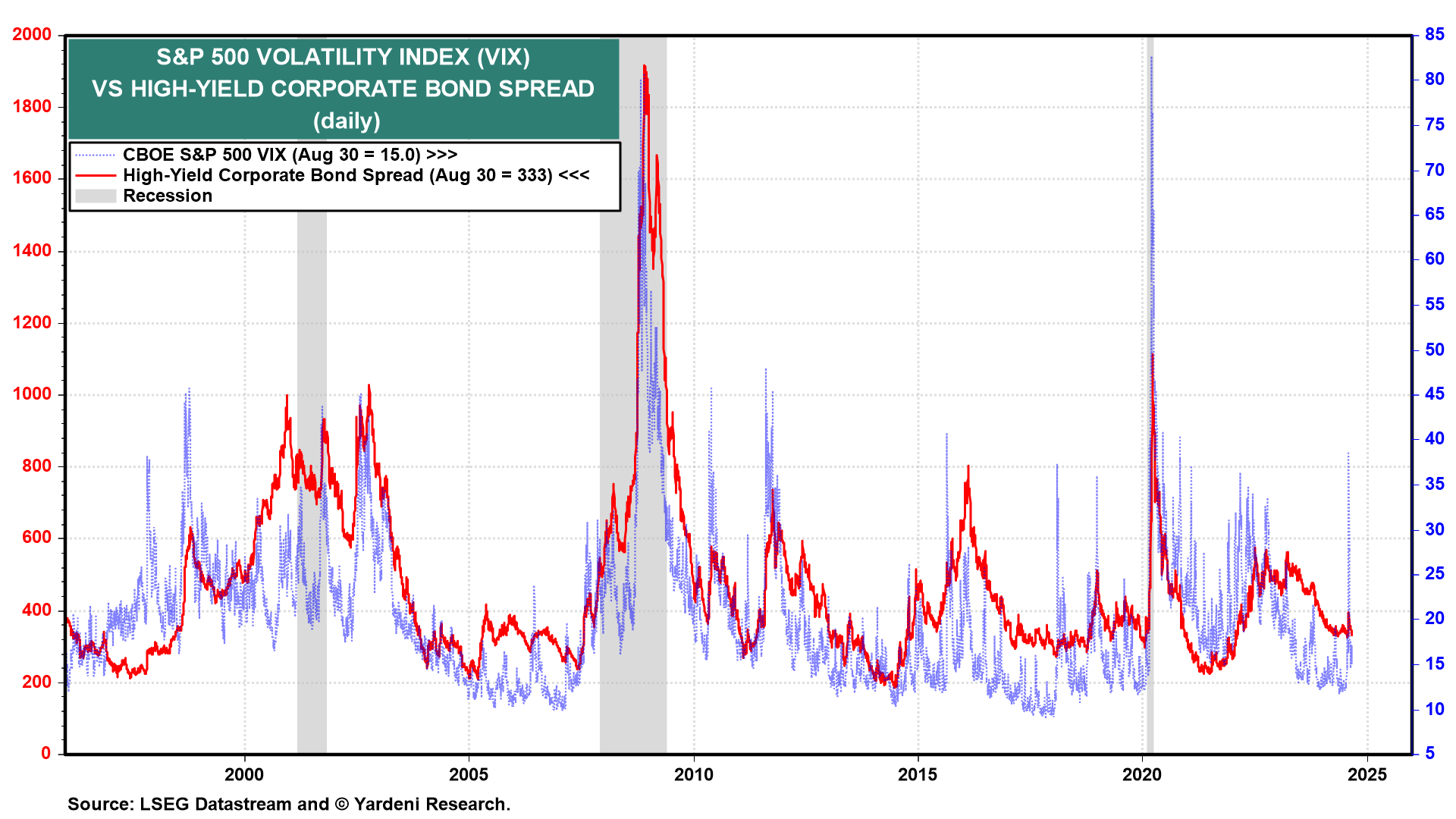

So far, there has been no credit crunch, as evidenced by the ongoing growth in loans and leases at commercial banks and the narrow yield spread between high-yield corporate bonds and the 10-year US Treasury bond.

4. The Godot recession is still MIA

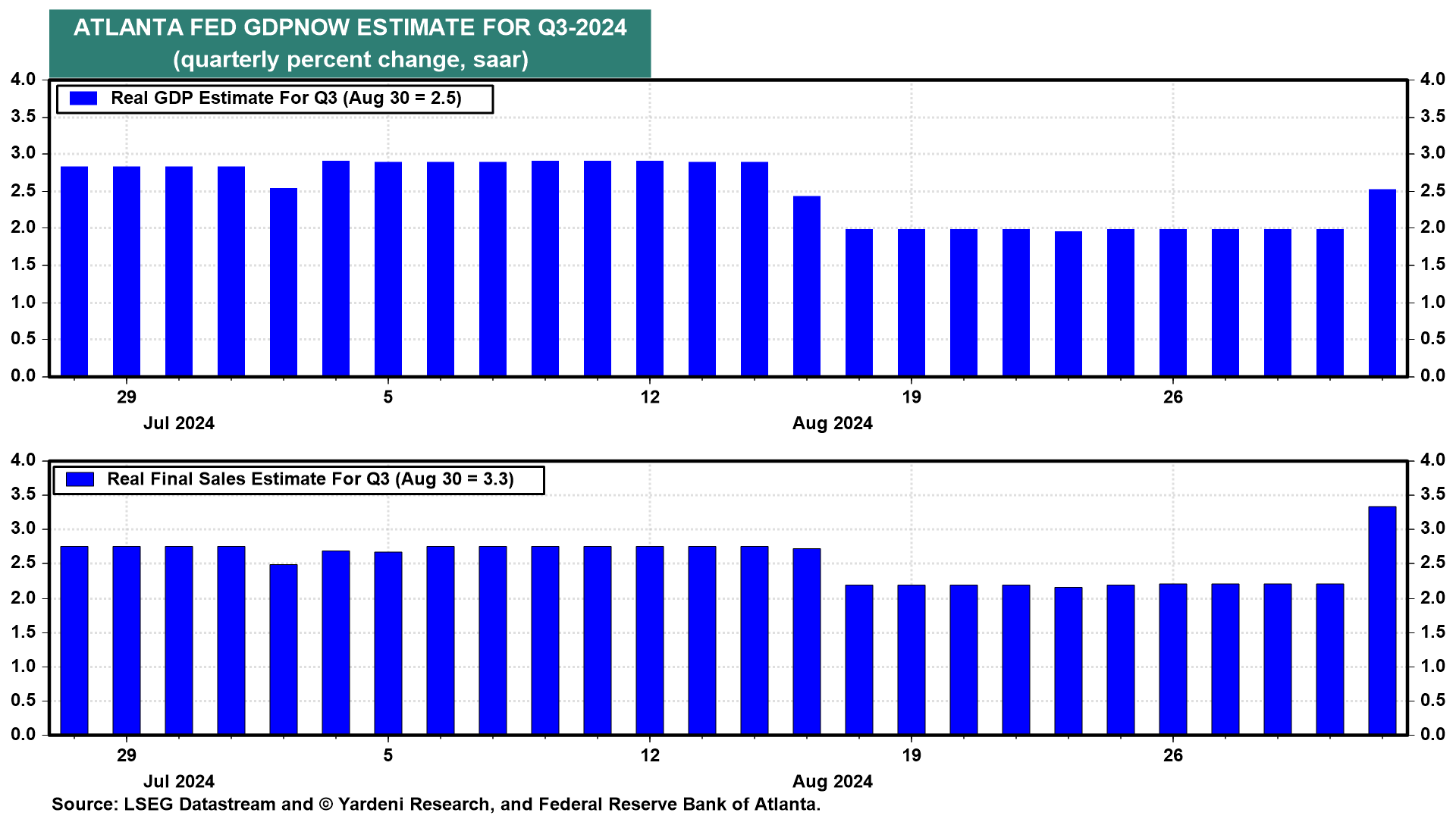

So far, the most widely anticipated recession of all times remains a no-show. Real GDP has been rising to new record highs since Q3-2022 through Q2-2024, which was revised last Thursday from up 2.8% (saar) to 3.0%.

On Friday, following the release of July’s consumer spending report, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracking model estimate for Q3-2024 real GDP growth was raised from 2.0% to 2.5%, with real final sales revised up from 2.2% to 3.3%!

5. The long-and-variable-lags myth

And what about the dreaded “long and variable lags” between the tightening of monetary policy and economic downturns? It may be that as more borrowers have to refinance their debts at higher interest rates, they will be forced to retrench. If enough of them do so, that could cause a recession.

That’s possible, we suppose. However, we ascribe previous long and variable lags to the time between the initial hike in the federal funds rate during monetary policy tightening cycles and the triggering of a financial crisis.

Once that happened, there were no lags as the financial crisis quickly turned into a credit crunch and a recession. There is no precedent for the current situation to be found in previous monetary policy cycles. It really is different this time, so far.

6. Bottom line on the FFR outlook

What about Friday's weak employment report? The workweek rose, sending aggregate hours worked to a new record high. Wages and salaries are rising faster than inflation. Real GDP is growing.

The Fed is committed to averting a recession and to stopping the unemployment rate from rising now that inflation is almost down to 2.0%.

Given the above, we think that the Fed will cut the federal funds rate by 25bps (not 50 bps) on September 18. There might be one more cut in either November or December. Next year, we expect four rate cuts.