Palantir shares slip premarket despite posting record revenue in third quarter

Bonds I: Kerfuffle. Bloomberg reported that JPMorgan Chase & Co. CEO Jamie Dimon said on the company’s Friday earnings call: “There will be a kerfuffle in the Treasury markets because of all the rules and regulations. When that happens, the Fed will step in—but not until ‘they start to panic a little bit.’ He added, ‘When you have a lot of volatile markets and very wide spreads and low liquidity in Treasuries, it affects all other capital markets. That’s the reason to do it, not as a favor to the banks.’”

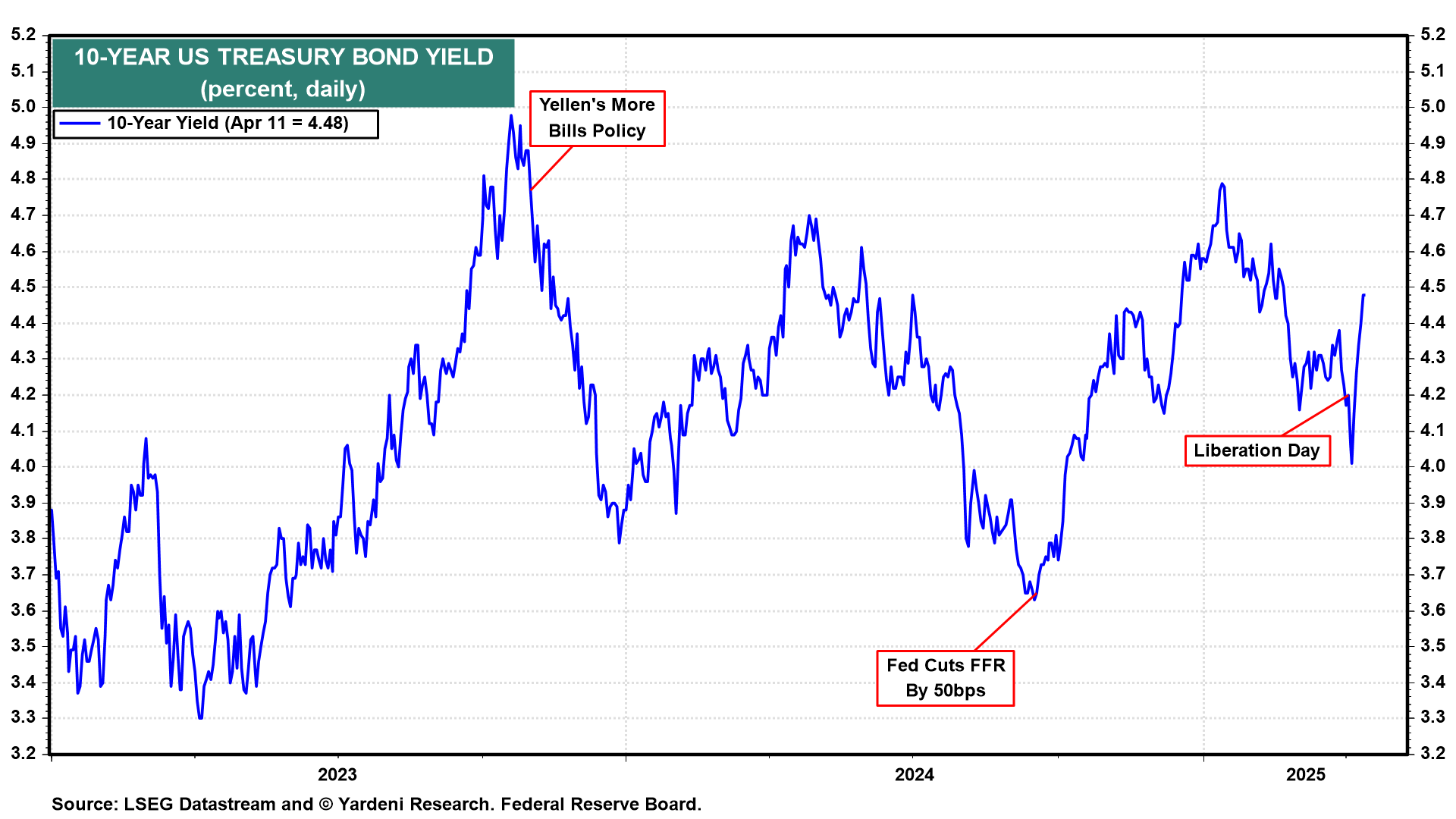

There has already been a kerfuffle in the bond market since April 2, i.e., on President Donald Trump’s self-proclaimed “Liberation Day,” when he announced higher-than-expected reciprocal tariffs on 60 countries, including an island populated only by penguins. The tariffs were scheduled to take effect on April 9, when they were postponed for 90 days because of the bond market’s kerfuffle. The tariffs on China, however, were implemented. The 25% tariff on aluminum, steel, and autos remained in place.

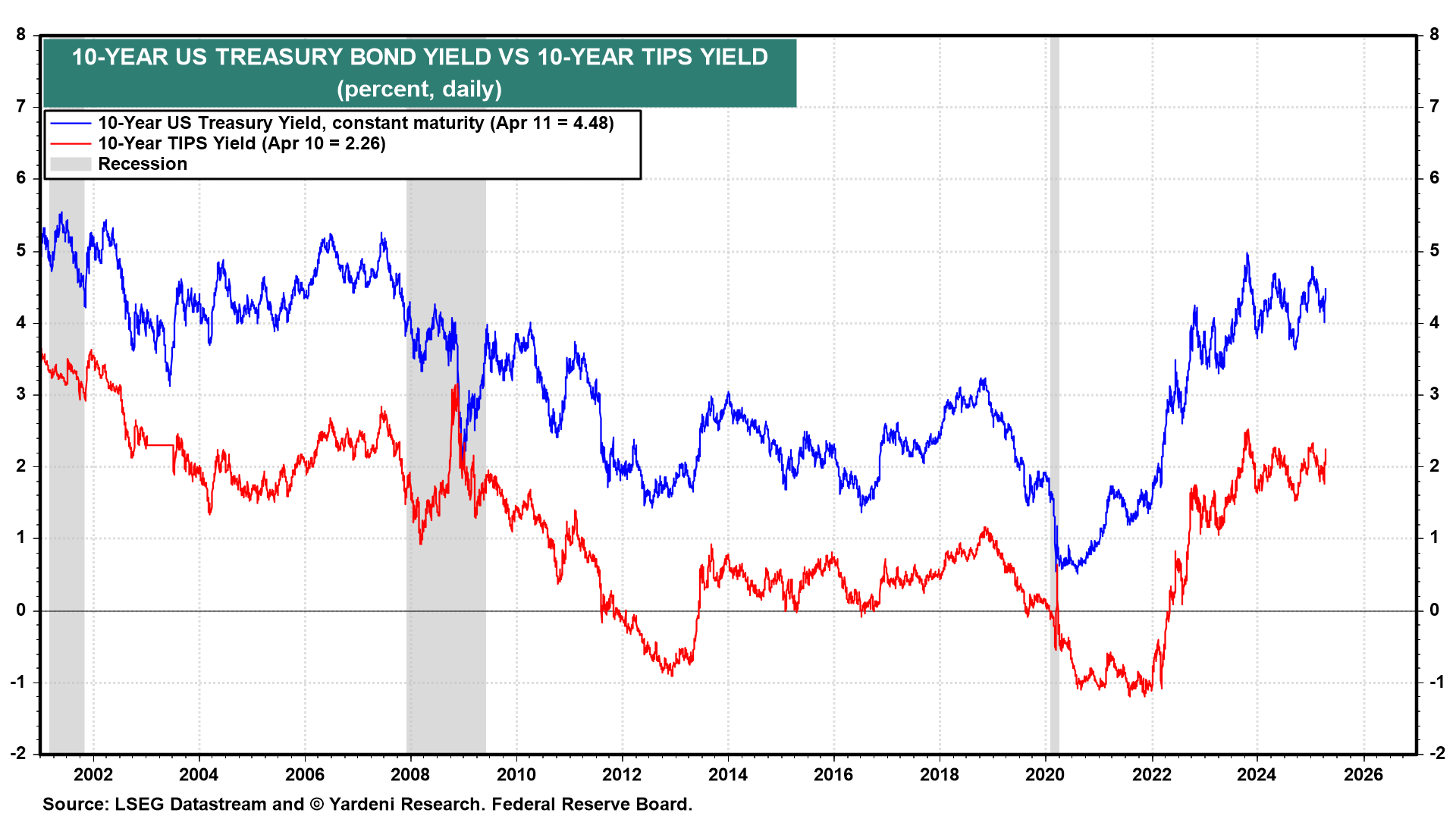

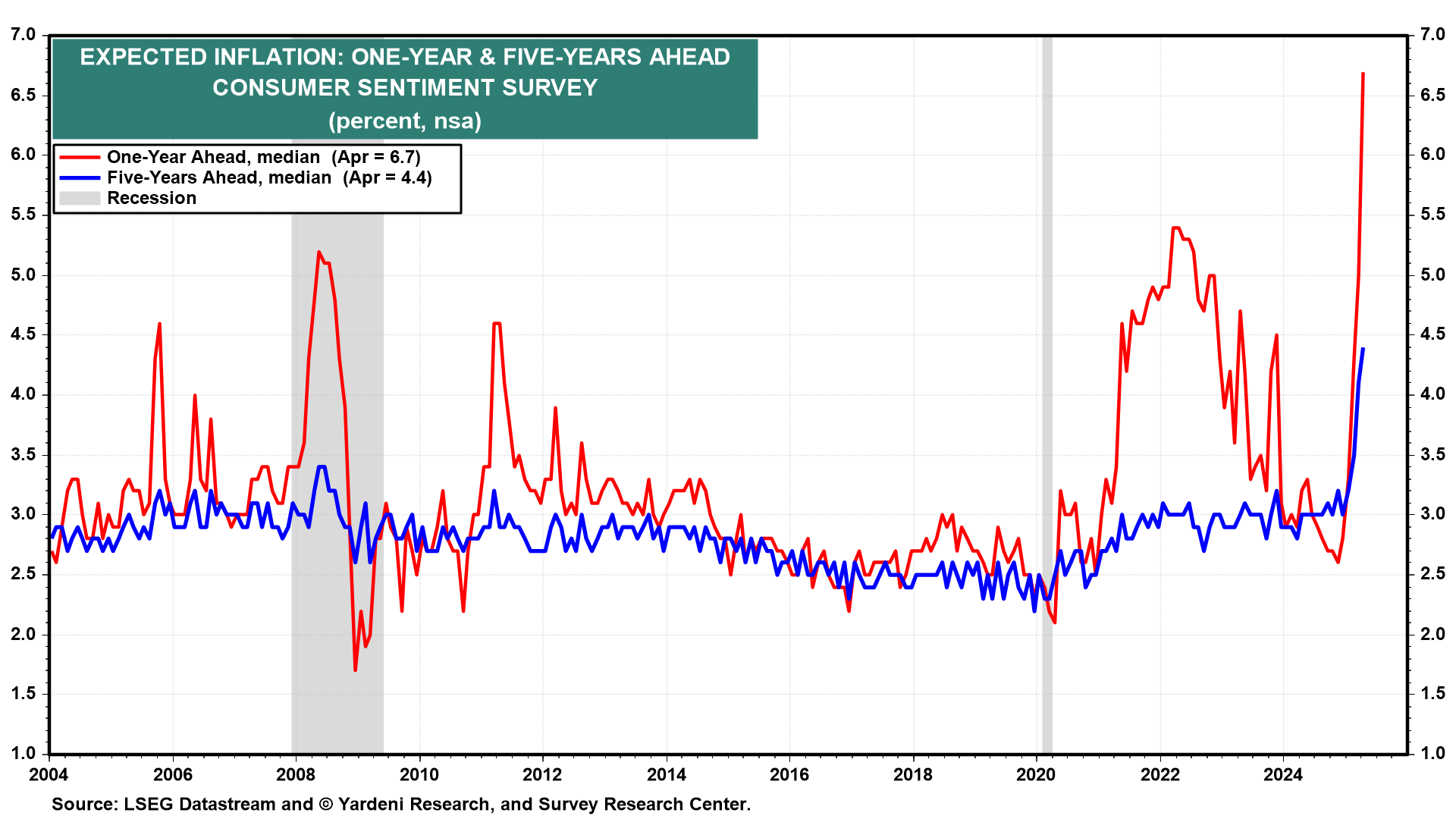

Trump acknowledged that he postponed the tariffs because of the bond market’s kerfuffle. The 10-year Treasury bond yield did fall slightly during April 3 and April 4 to 4.01%. But then it climbed to 4.49% on Friday, April 11. That happened despite lower-than-expected March Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Producer Price Index (PPI) readings on April 10 and April 11. Even the sharp drop in consumer sentiment during the first two weeks of April (reported on April 11) didn’t stop the bond yield from moving higher, as it would have in normal times.

The problem is that Trump’s Tariff Turmoil (TTT) is expected to be inflationary, as evidenced by the big jump in consumers’ inflationary expectations during the first two weeks of April. This means that rising inflation likely would delay any Fed easing to avert a recession. Fed officials aren’t about to lower the federal funds rate (FFR) anytime soon, as they have been saying since the beginning of the year. In an April 4 speech, Fed Chair Jerome Powell suggested that they’re in even less of a hurry to do so now than before TTT, since the tariffs turned out to be higher than widely expected:

“While uncertainty remains elevated, it is now becoming clear that the tariff increases will be significantly larger than expected. The same is likely to be true of the economic effects, which will include higher inflation and slower growth. The size and duration of these effects remain uncertain. While tariffs are highly likely to generate at least a temporary rise in inflation, it is also possible that the effects could be more persistent. Avoiding that outcome would depend on keeping longer-term inflation expectations well anchored, on the size of the effects, and on how long it takes for them to pass through fully to prices. Our obligation is to keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored and to make certain that a one-time increase in the price level does not become an ongoing inflation problem.”

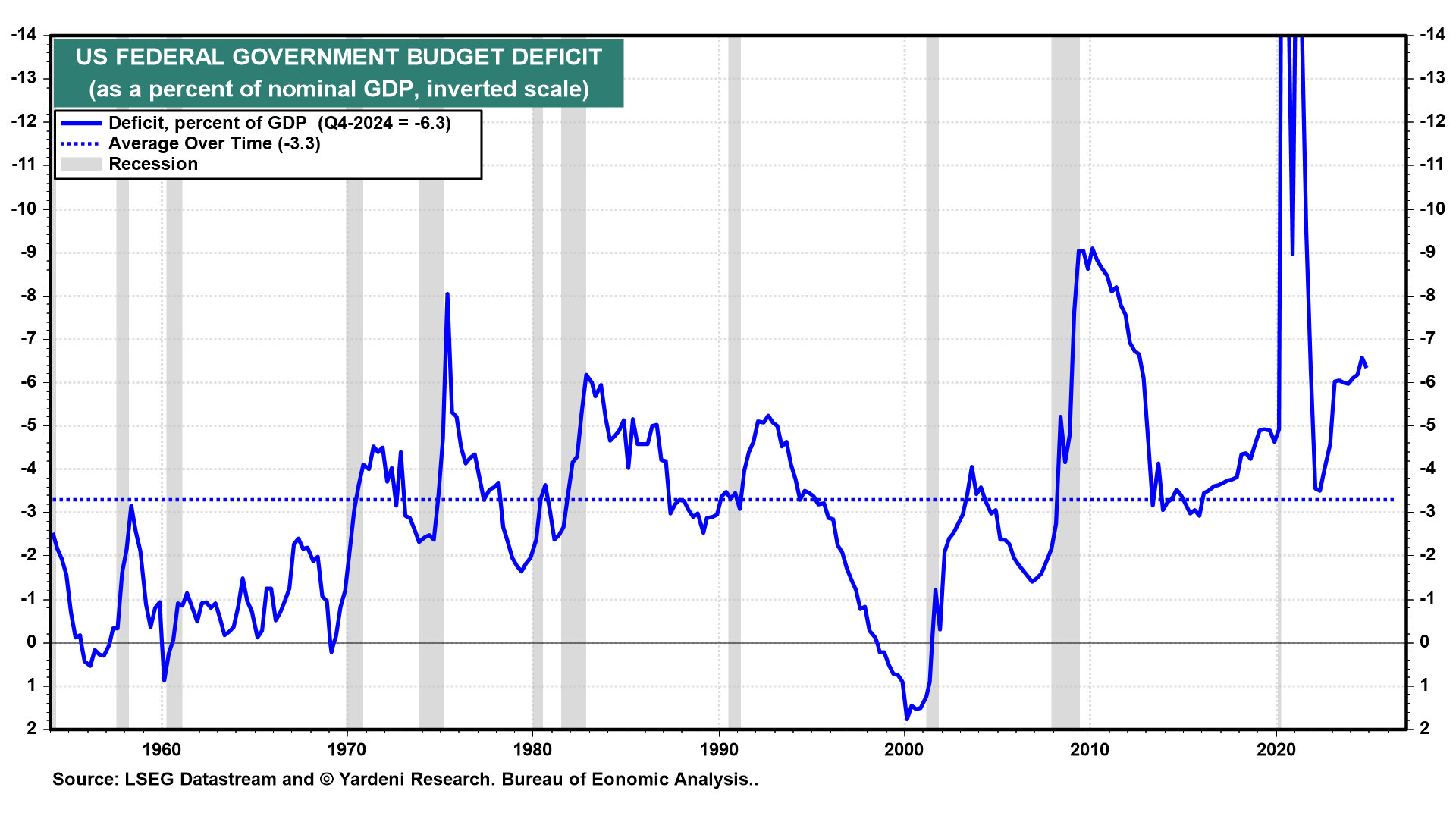

So bond investors may be in no rush to buy bonds, especially since they may not be convinced that Washington will do enough to reduce the federal deficit.

On Friday and Saturday, Trump continued to back off from his tariffs, which he has described as “a beautiful thing.”

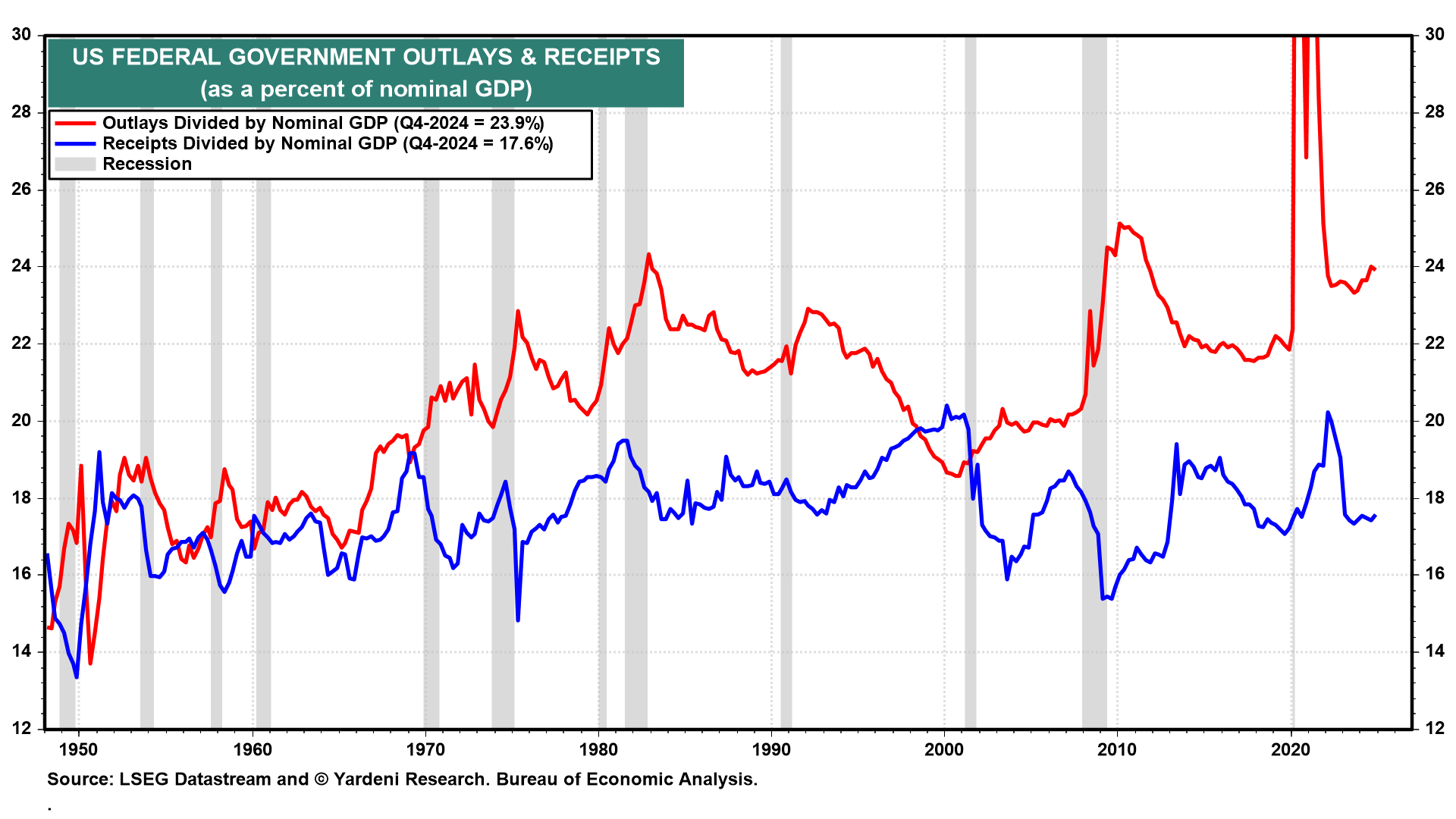

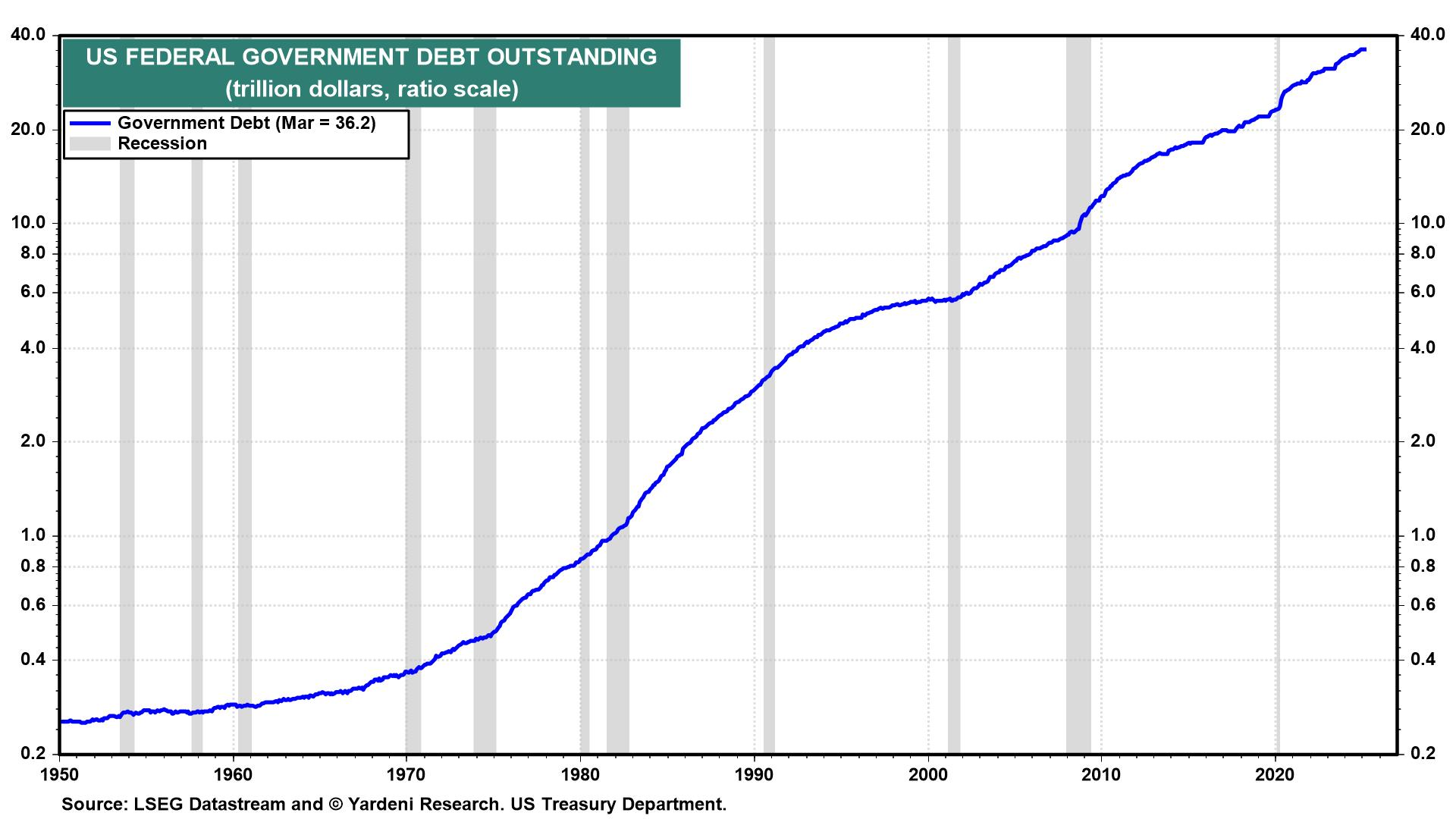

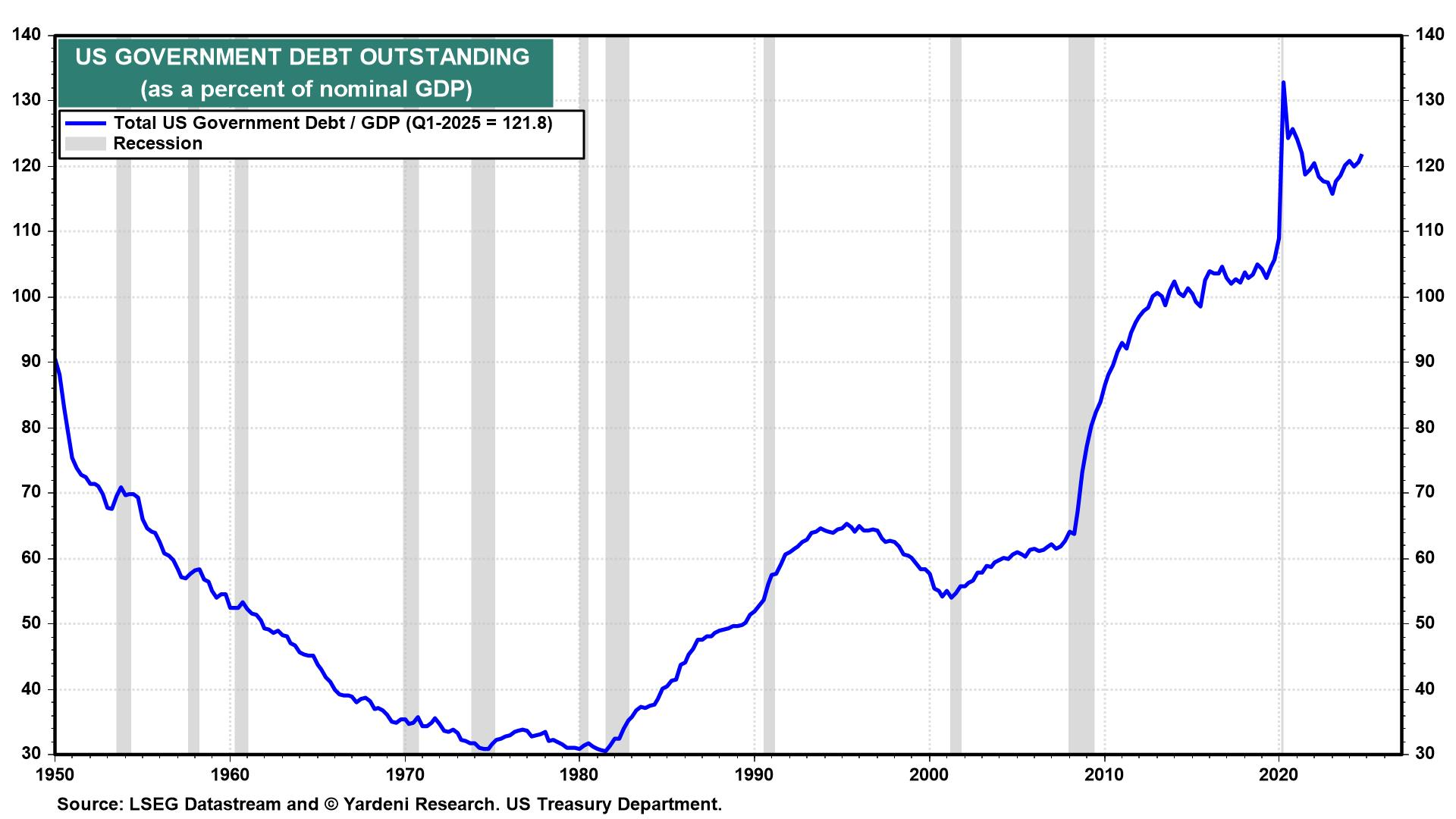

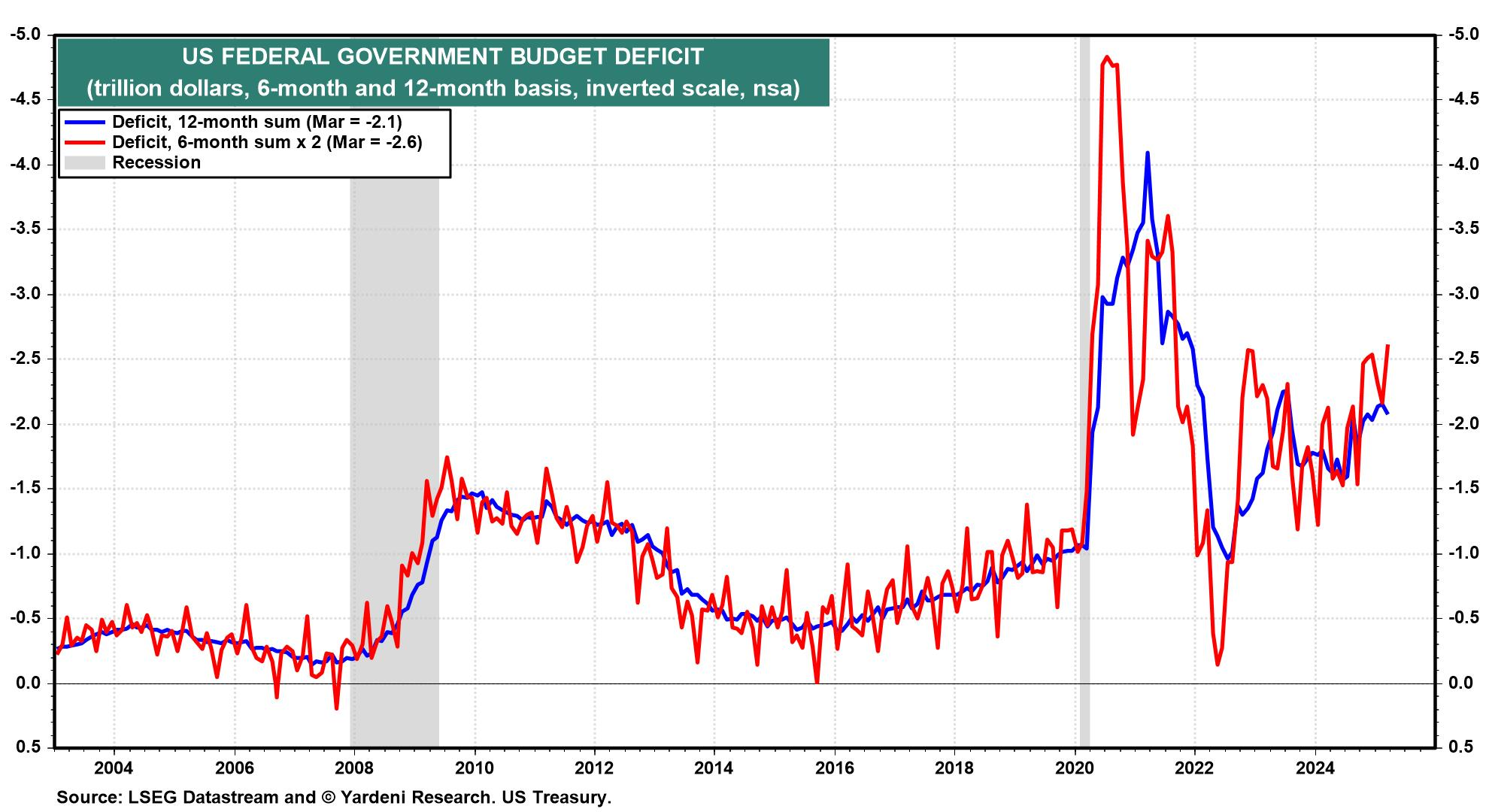

Bonds II: The Yellen/Bessent Short-Term Solution to Debt. I have been on Wall Street for more than 45 years. Over that period, there has been a lot of concern about mounting federal deficits and debt. Along the way, some of us bond market watchers observed that bond yields tended to decline when federal budget deficits widened during recessions; that’s because recessions caused the federal government’s revenues to decline, as Americans’ incomes and profits fell, and the government’s outlays to be boosted by its income support programs. Deficits were mostly counter-cyclical, widening during recessions and narrowing during expansions. No big deal.

Yet starting in the 1980s, there were mounting concerns that federal government debt was rising relative to nominal GDP as deficits continued even during periods of economic expansion.

Lots of articles and books have been written since the 1980s about the likely terrible consequences of so much government debt rising so rapidly. Stock and bond market bears often included the federal deficits and debt in their litany of reasons to be cautious. I tended to be mostly bullish on stocks and bonds in the past. With regards to federal government deficits and debt, I argued that I would worry about them when the bond market worried about them.

I did briefly worry in 2023, when the 10-year Treasury bond yield jumped from 4.00% on August 9 to 5.00% on October 19. This resulted from bond investors’ response to a series of Treasury auction size increases starting in August 2023, with quarterly refunding auctions for 3-year, 10-year, and 30-year maturities reaching $125 billion. These poorly received auctions heightened fears that a debt crisis was imminent. The bond market was choking on the supply of bonds, forcing yields up to levels that could cause a recession.

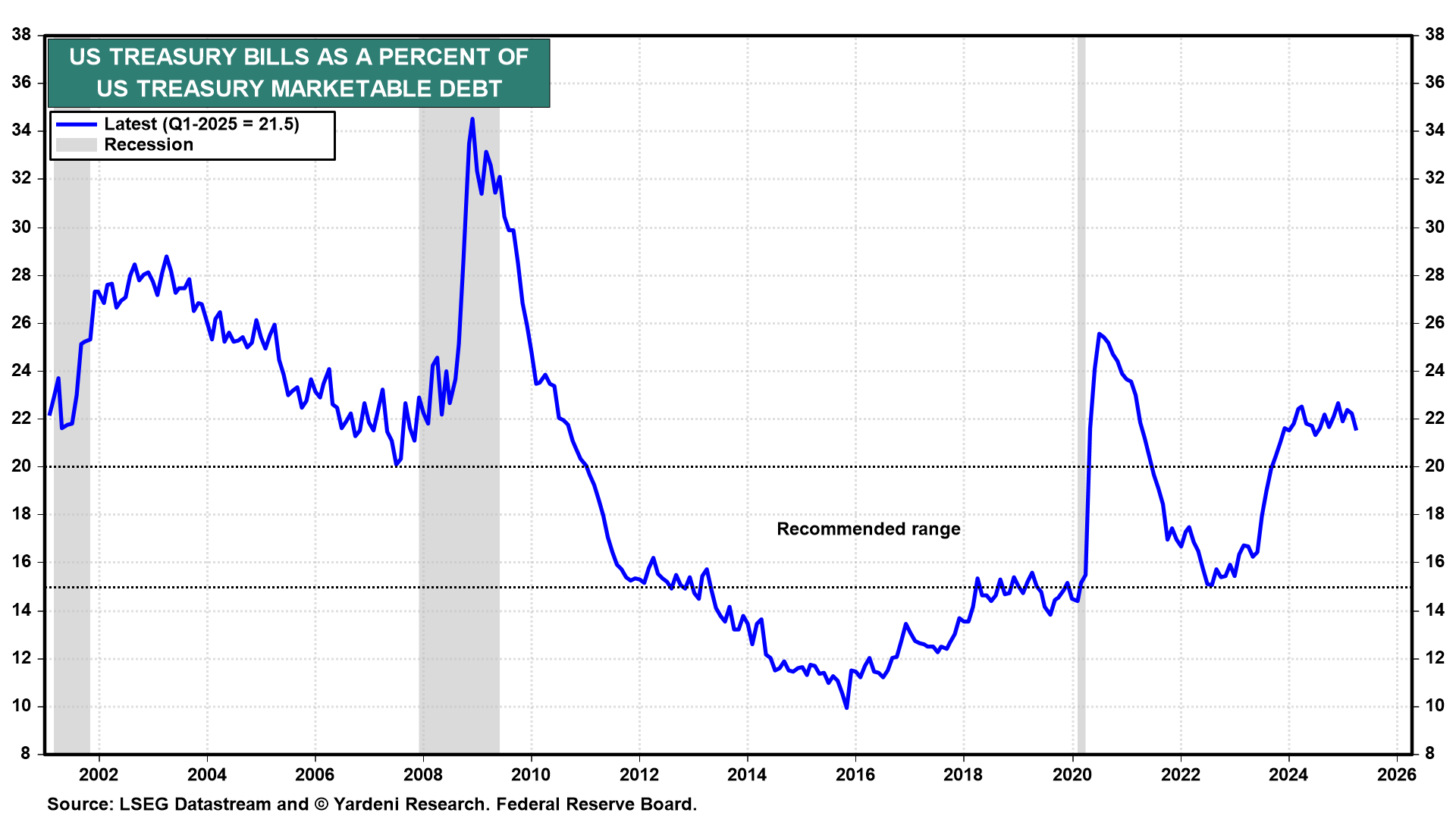

On November 1, 2023, the US Treasury, under Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, announced a reduction in the pace of increases for longer-dated Treasury securities, easing the supply of new bonds. Yellen’s strategy leaned heavily on issuing short-term Treasury bills to meet borrowing needs. The Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, which advises the Treasury Department on matters related to the issuance of federal securities, has been recommending that no more than 20% of the Treasury’s marketable debt should be held in Treasury bills. Yellen took the ratio up to 22%.

This tactic was criticized by some, including current Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, for potentially keeping borrowing costs artificially low ahead of the 2024 election. When Bessent took over as Treasury secretary in early 2025, he initially criticized Yellen’s approach, arguing it shortened debt maturities too much and clashed with the Federal Reserve’s inflation goals. However, on February 5, 2025, the Treasury under Bessent announced that it would maintain Yellen’s guidance, keeping longer-term debt issuance unchanged at $125 billion for quarterly refunding auctions spanning 3-, 10-, and 30-year maturities, with no increases expected for “at least the next several quarters.”

“He and I are focused on the 10-year Treasury,” Bessent said in a February 5 interview with F Business when asked about whether President Trump wants lower interest rates. “He is not calling for the Fed to lower rates.”

Bessent explained his continuation of Yellen’s plan in a February 20, 2025, Bloomberg Television interview, stating that any shift to Treasury’s issuing new debt with longer maturities was “a long way off” due to market conditions, inflation, and the Fed’s quantitative tightening. He suggested a gradual approach, as flooding the market with long-term bonds could spike yields and borrowing cost.

I will not be surprised if Bessent addresses the recent turmoil in the Treasury bond market by reducing the size of Treasury bond auctions, thus financing even more of the deficit with Treasury bills. The next quarterly refunding announcement is scheduled for April 30. That would certainly push bond yields lower. In effect, this would amount to a policy of Yield Curve Control by the Treasury (YCC-T) rather than the Fed (YCC-F).

As a thought experiment, what if the Treasury issued only Treasury bills? The Fed would be forced to buy a significant amount (if not all) of them to keep the FFR from rising above its range. Bond yields would fall dramatically unless inflationary pressures resulted, in which case the Fed would have to raise the FFR range. That would immediately increase the cost of financing the Treasury’s debt. Might that put pressure on Congress and the White House to reduce the deficits? Probably not, because YCC-T would effectively bury the Bond Vigilantes.

Bonds III: Staying Vigilant. Since the start of this year, I’ve been arguing that the 10-year US Treasury bond yield has normalized and is likely to trade in a range of 4.25%-4.75% for the rest of this year. I flinched after Liberation Day and lowered the range to 3.75%-4.25%. But now, I am raising it back to 4.25%-4.75%, which is where the bond yield mostly traded in the years just before the Great Financial Crisis.

So the recent increase in the yield doesn’t faze me. But it has fazed lots of other market observers. Indeed, I’ve been fielding lots of calls from financial market journalists wondering whether the Bond Vigilantes are back on the scene. The answer is “no” if the bond yield simply has normalized. Then again, the recent jump in yields has been fast and furious, suggesting that the Bond Vigilantes are back and that on Wednesday of last week they forced the Trump administration to postpone imposing reciprocal tariffs on numerous countries around the world for 90 days.

The Bond Vigilantes are rightly concerned that Trump’s Nitro Tariffs (TNT) will cause an explosive increase in inflation. They are also concerned that the recent weakness in the dollar suggests that foreigners are selling their US bonds. And the Bond Vigilantes might be signaling that they aren’t convinced that the Trump administration will rein in the federal deficit.

The good news is that Treasury Secretary Bessent seems to have convinced President Trump that they shouldn’t mess with the Bond Vigilantes. On Wednesday, April 9, after ratcheting back all reciprocal tariffs to 10% for at least 90 days (but upping the pressure on China with a 145% tariff), Trump said: “I was watching the bond market. The bond market is very tricky, I was watching it. But if you look at it now it’s beautiful. The bond market right now is beautiful. I saw last night where people were getting a little queasy.”

Trump also said he listened to JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon’s interview last Wednesday with Fox’s Maria Bartiromo, in which Dimon said a recession was likely and the bond market was sending bad signals about stress in the financial plumbing.

President Bill Clinton had a similar epiphany in 1993 after his advisor James Carville said: “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the President or the Pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

Bonds IV: Supply & Demand. Everyone in our business seems to be wondering why the 10-year Treasury bond yield has been rising in recent days.

The widely accepted view is that hedge funds had to unwind basis trades by selling bonds when the yield became volatile in response to TNT. But also among the usual roundup of suspects is the Chinese government, which might be selling Treasuries in retaliation against Trump’s 145% tariff on goods imported from China.

Reporter Jon Sindreu came up with a clever explanation in an article posted by The Wall Street Journal on April 11 titled “The Simple Explanation for This Week’s Treasury Market Mayhem.” He wrote: “But the answer might be far simpler: U.S. government debt is doing badly because, well, investors don’t want to buy it.” In other words, bond yields are rising because there are fewer buyers than sellers of US Treasury bonds.

Consider the following:

(1) The biggest seller of those bonds, of course, is the US Treasury. Yet Reuters reported on April 9: “A U.S. Treasury debt auction of $39 billion in benchmark 10-year notes was well received on Wednesday, showing solid investor demand even after a bond market sell-off driven by an escalating trade war between the United States and its major trading partners led by China. The U.S. Treasury’s auction came in better than expected, priced at a high yield of 4.435%, lower than the rate forecast at the bid deadline.” Indirect buyers, a category that typically includes foreign central banks and private investors, bought 87.9% of the supply allotted to them, above the average of 70%.

(2) March’s CPI and PPI inflation rates were lower than expected, we learned when released on Thursday and Friday. Yet the bond market wasn’t impressed. That’s because on Thursday, the Treasury Department reported that the federal deficit was $2.1 trillion over the 12 months through March, and on Friday the Survey Research Center reported that the Consumer Sentiment Survey showed that consumers’ year-ahead expected inflation had soared to 6.7% last month, the highest rate recorded since 1981.

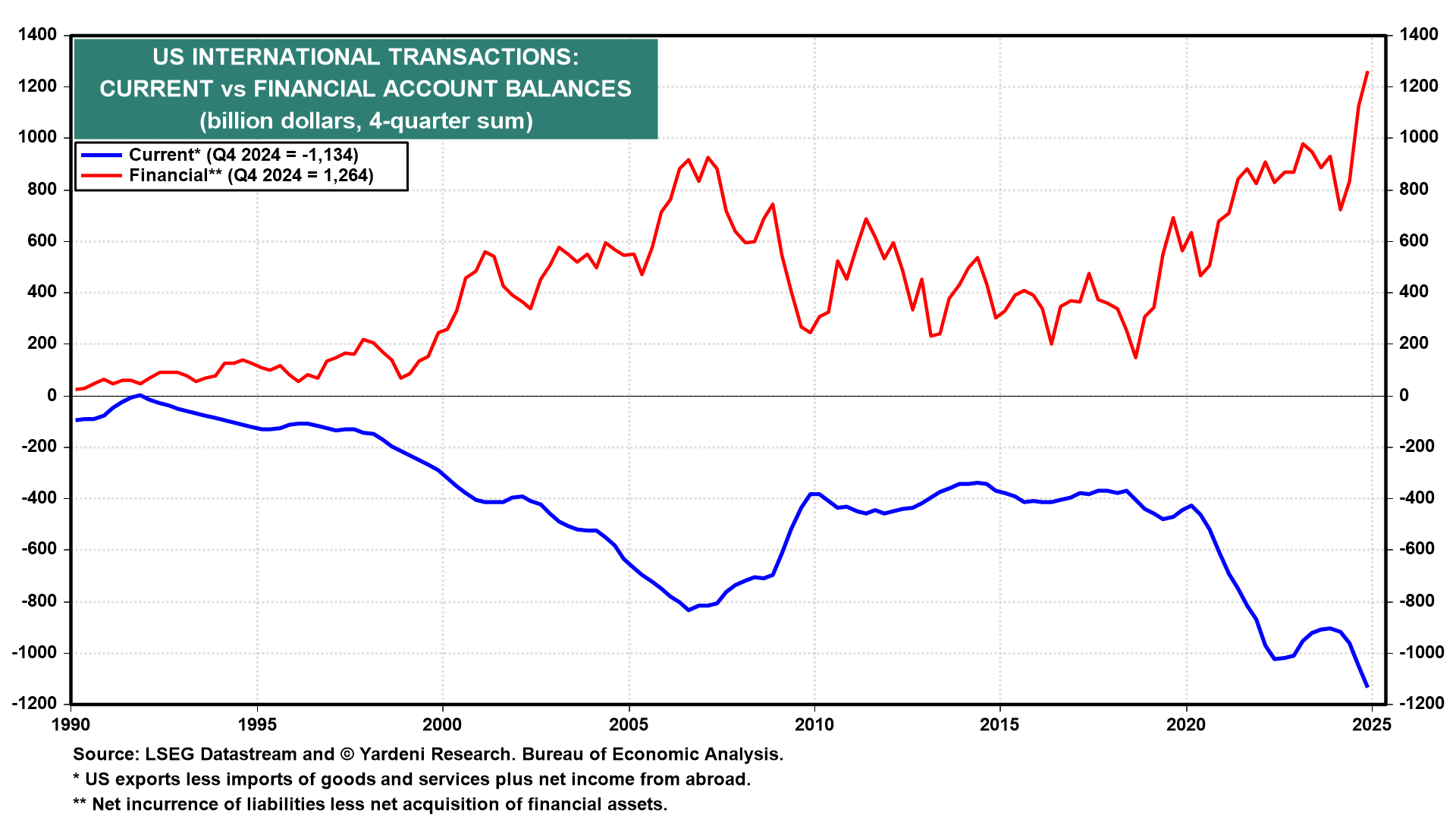

(3) Bessent should explain to the President that the balance of payments always balances. The flip side of America’s current account deficit are net capital inflows.

So for example, last year, the former totaled $1.13 trillion, while the latter totaled $1.26 trillion. This suggests that if Trump succeeds in reducing the trade deficit, foreigners will have fewer dollars with which to buy US Treasuries and other securities.