ION expands ETF trading capabilities with Tradeweb integration

Since Berkshire Hathaway’s (NYSE:BRKb) (NYSE:BRKa) launch, the conglomerate is up over 5.5 million percent. How did Warren Buffett do it?

Introduction

Warren Buffett’s announcement that he will step down as chief executive of Berkshire Hathaway marks the end of a financial epoch. For over half a century, Buffett has stood not just as a titan of investing, but as a living challenge to the idea that prevailing academic theory that markets are efficient and that no one can consistently beat the system. Through a strategy that defied short-termism and market noise, he built one of the most valuable conglomerates in history and, in the process, became one of the world’s richest and most trusted financial figures.

Buffet often attributes his success to intuitive brilliance or once-in-a-generation stock picking. In reality, his sustained outperformance is grounded in a deliberate combination of structural advantages, disciplined investment principles, and extraordinary personal traits. It’s not merely about choosing the right stocks; it’s about building an ecosystem where long-term value creation can thrive without interference.

As the post-Buffett era begins, understanding the mechanics behind his enduring success is not just a matter of tribute but of practical insight for investors, institutions, and market thinkers alike.

Quality, Leverage and The Berkshire Model

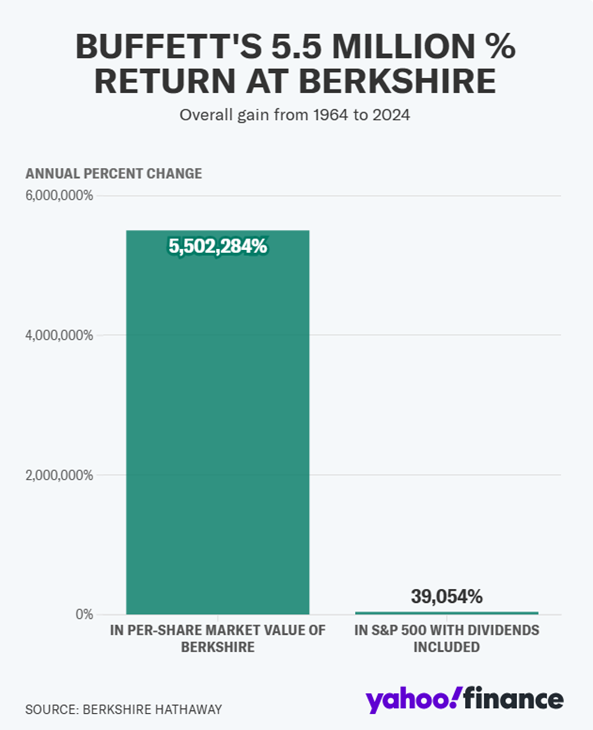

Warren Buffett’s track record at Berkshire Hathaway is widely recognised: since 1965, Berkshire Hathaway stock has returned 5,502,284%. At the same time, the S&P 500, with dividends included, provided a return of 39,054%. Berkshire Hathaway’s compound annual gain over that period tallied 19.9%.

The S&P 500’s return was 10.4%. While Buffett’s success is often credited to his ability to pick the right stocks, a deeper explanation lies in the structural foundation he built around those decisions. His long-term performance reflects a combination of disciplined investment selection, access to low-cost and long-duration capital through insurance operations, and a business model designed to support consistent, long-horizon capital deployment.

A key component of this performance is Buffett’s adherence to a well-documented factor-based approach. According to the 2018 paper “Buffett’s Alpha” by Andrea Frazzini, David Kabiller, and Lasse Heje Pedersen of AQR Capital Management, Berkshire Hathaway’s returns can be largely attributed to consistent exposure to cheap, high-quality and low-volatility stocks. The study estimates that Buffett operated with an average leverage ratio of 1.9-to-1, meaning that for every dollar of equity, he controlled $1.90 in assets.

However, the practical application of this model goes beyond abstract financial ratios. Buffett did not passively target factor exposures; he selected businesses where profitability, capital efficiency, and resilience could be observed and sustained.

Examples include long-term holdings such as Coca-Cola (NYSE:KO), which delivered stable operating margins above 25% for decades, and American Express (NYSE:AXP), whose return on equity has consistently exceeded 25% in most years since Berkshire’s investment.

Source: Bloomberg

The source of this leverage is central to understanding Buffett’s structural advantage. Through Berkshire’s insurance subsidiaries, particularly GEICO and National Indemnity, the firm collects premiums that constitute the “float”, which is capital held between the time premiums are received and claims are paid.

At the end of 2024, Berkshire reported insurance float of $171 billion, which is ultimately capital that can be invested at no direct cost as long as underwriting remains profitable. This float operates similarly to borrowed capital but without the repayment pressure, interest cost, or liquidity risks associated with traditional debt. It allowed Berkshire to maintain long-term exposure to equities without the constraints of short-term funding structures or mark-to-market volatility.

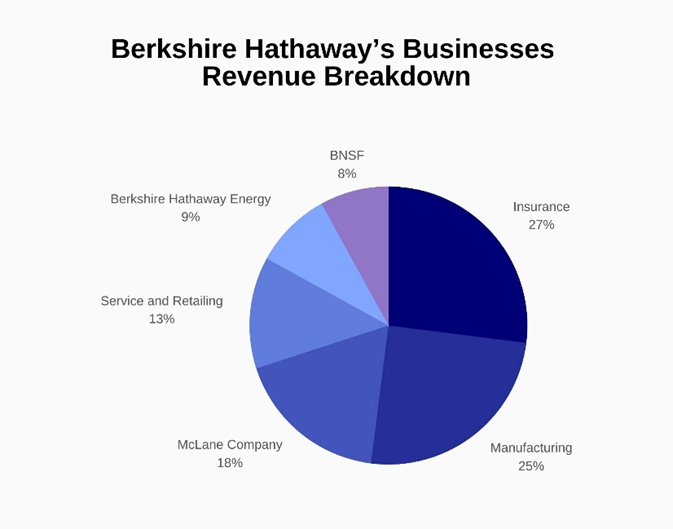

Alongside the insurance arm, Berkshire owns businesses that reinforce its financial flexibility. Subsidiaries such as BNSF Railway, Berkshire Hathaway Energy, and the Marmon Group generate reliable cash flows, buffering the company against market downturns. These businesses not only diversify income sources but also support liquidity and reduce dependence on capital markets.

Source: usesignhouse

This combination of durable leverage and internal cash generation has enabled Berkshire to accumulate significant liquidity. As of May 2025, Berkshire sold a net $1.5 billion of stocks and grew its cash pile and US Treasury bills to a record $348 billion.

This position is not a consequence of indecision but a deliberate policy. Buffett has consistently emphasised the importance of maintaining ample liquidity to act decisively when attractive opportunities emerge.

As he stated in a letter to shareholders: “Having loads of liquidity, though, lets us sleep well. Moreover, during the episodes of financial chaos that occasionally erupt in our economy, it allows us to act quickly and decisively.”

The availability of such reserves allows for capital deployment without external financing or forced asset sales and reflects a long-term investment horizon rarely matched at comparable scale.

The interplay between structure and discipline is critical. Berkshire’s ability to allocate capital freely, without pressure from short-term shareholders or external lenders, stems from its design.

Unlike investment funds subject to redemption cycles or regulatory leverage limits, Berkshire’s model integrates insurance, operating businesses, and a holding company under one umbrella. This configuration provides durable capital and organisational stability, supporting the execution of a consistent investment philosophy over time.

In sum, the foundation of Buffett’s success lies in the architecture of Berkshire Hathaway itself. The convergence of patient capital, low-cost leverage, diversified operating income, and capital discipline created an environment in which long-term compounding was not only possible but systematically supported.

Rather than relying solely on exceptional investment decisions, Buffett engineered a financial structure that minimised disruption and maximised staying power.

The Human Factor

Behind Berkshire Hathaway’s structural strength lies another dimension: Warren Buffett’s personal temperament and behavioural discipline. His success cannot be fully understood through numbers alone. It stems equally from psychological traits, patience, consistency, and communication, that shaped both his investment strategy and the institution he built.

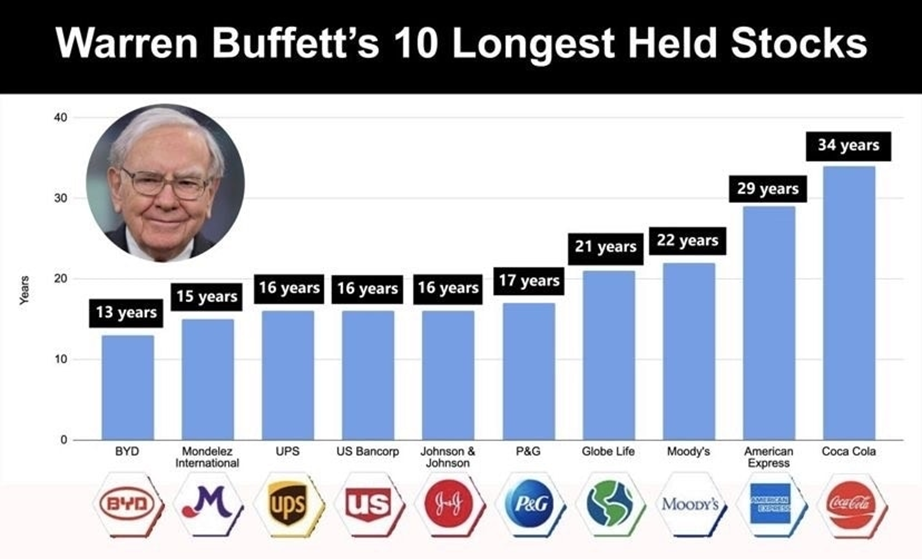

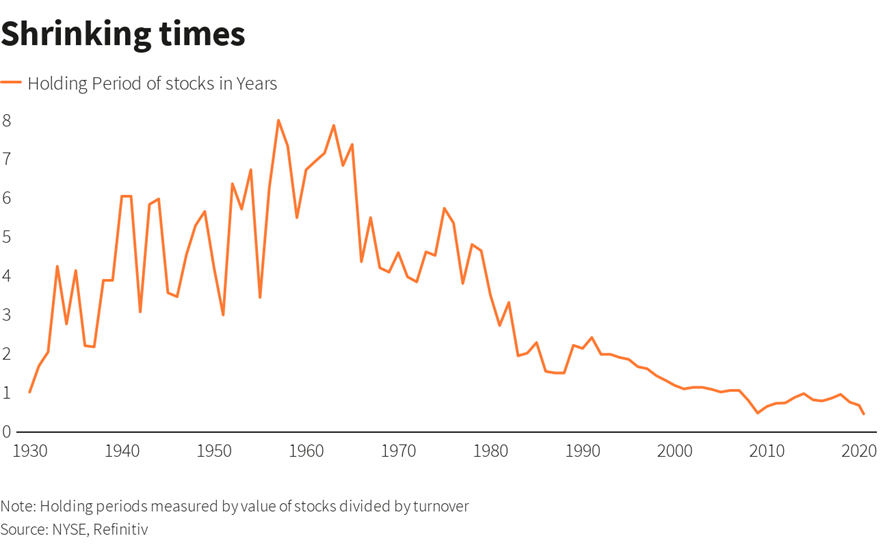

Buffett’s investment horizon is measured not in quarters or years, but decades. While many investors rotate portfolios every few months, Berkshire has held some of its core positions, such as Coca-Cola and American Express, for over 25 years, contrasting strongly with the fact that the average holding time for securities in an average investor’s portfolio is a mere six months.

This long-termism has allowed the effects of compounding to fully materialise. As Buffett famously stated in his 1988 letter, referring to Coca-Cola: “Our favourite holding period is forever.”

Source: Moomoo

This extended time frame wasn’t just philosophical; it was possible because Buffett structured his environment to avoid the typical pressures that force other investors into short-term thinking. Berkshire Hathaway has no quarterly earnings guidance, as he expressed in an interview with CNBC: “I do not like guidance. I think the guidance leads to a lot of bad things, and I’ve seen it led to a lot of bad things.”

On the contrary, mutual funds and hedge funds operate under redemption risk: if returns lag for a few quarters, clients may pull out money, forcing managers to liquidate assets.

These structural limits create career risk, which Buffett has never faced. In fact, his investors, many of them long-term shareholders who read his letters annually, have largely embraced his patience and discipline, even during periods of underperformance. This trust gave Buffett the rare ability to act consistently, despite market volatility or public criticism.

One remarkable example of this trust was during the dot-com bubble. As the tech-heavy NASDAQ surged nearly 86% in 1999, Buffett avoided internet stocks entirely, warning they lacked durable moats or earnings.

Berkshire underperformed badly that year, gaining just 0.5% compared to the S&P 500’s 21%. Yet investors stuck with him, and when the bubble burst in 2000, Berkshire’s disciplined value strategy was vindicated.

This exceptional trust is not anecdotal, it’s measurable. In a leadership study conducted by the Thunderbird School of Global Management, Warren Buffett was crowned America’s Most Admired CEO, with 94% of respondents rating him highest in trust.

As Jeff Cunningham, former Forbes publisher and editor of the report, noted, Buffett led the rankings across nine leadership attributes, including empathy, integrity, and personal dynamism. His reputation for fairness and clarity has made him not just a financial icon, but a leadership benchmark in corporate America.

Reinforcing this was Buffett’s unique ability to communicate, not just with shareholders, but with the public. His annual letters to shareholders, written in plain English with dry humour and moral clarity, have become essential reading in finance.

They not only explained Berkshire’s decisions but educated readers on sound investing.

In 2014, reflecting on 50 years of running the firm, Buffett wrote: “Our goal is to communicate with you in a manner that we would wish you to use if our positions were reversed – that is, if you were Berkshire’s CEO while I and my family were passive investors, trusting you with our savings.”

This trust and transparency had real financial consequences. During the 2008 financial crisis, Berkshire was able to strike landmark deals with Goldman Sachs and General Electric (NYSE:GE), offering capital in exchange for preferred shares with attractive terms.

The market interpreted Buffett’s involvement as a vote of confidence, which helped stabilise sentiment. These deals were only possible because Buffett had both cash and credibility, two assets that few investors possess simultaneously.

The combination of character, structure, and capital gave Buffett a behavioural advantage that compounded over decades. This is why attempts to replicate his model have largely failed. Several hedge funds, private equity firms, and asset managers have acquired insurance companies to mimic Berkshire’s access to float—but few have been able to underwrite profitably while investing with discipline.

Conclusion

Warren Buffett’s legacy is not defined by a single insight or strategy, but by an entire system built to defy the short-termism that governs much of the financial world. Unlike fund managers constantly at risk of redemptions or performance-based dismissal, Buffett engineered an ecosystem that protected him from external pressures.

His use of insurance float, combined with cash-generating subsidiaries, gave him a constant supply of low-cost capital. This allowed him to act when others were paralysed, and to hold when others were forced to sell.

Just as important were the human elements: patience, consistency, and an extraordinary level of trust from shareholders. While most investors are compelled to chase quarterly gains or follow market trends, Buffett stayed the course, even when it meant short-term underperformance. His annual letters, plain-spoken yet insightful, helped cement a bond of credibility rarely seen in corporate America.

In the end, Buffett’s true strength lies in his ability to combine sound financial principles with structural foresight and behavioural discipline. He didn’t just play the game better; he changed the rules in his favour.

As the post-Buffett era begins, the challenge is not only to emulate his investments but to understand, and try to recreate, the foundation that made them possible.