Is this U.S.-China selloff a buy? A top Wall Street voice weighs in

It’s been an unusually rough year for bond investing, but there are hints that the market is forecasting that the worst has passed. If correct, shifting to a risk-on posture offers the opportunity for hefty returns going forward.

As always with trying to divine the future for markets there’s no way to know if an upbeat outlook for bonds is premature. But for investors willing and able to tolerate timing risk — i.e. the potential for ongoing losses — the recent revival in bond prices suggests it’s timely to bet that bear market for fixed-income markets may be ending.

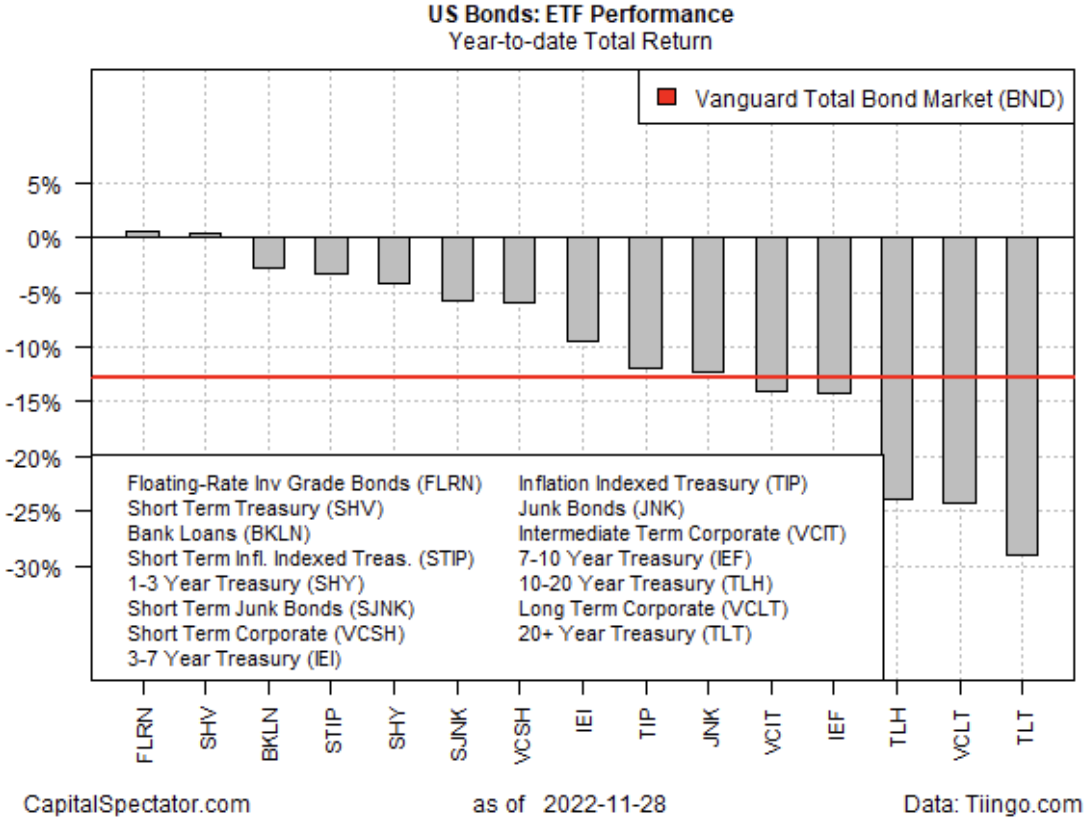

What is clear is that losses for US bonds are unusually steep year to date, based on a set of ETF proxies. Except for short-term Treasuries (SHV) and floating-rate bonds (FLRN), all the major slices of US fixed-income markets are in the red, in some cases dramatically so. The biggest loser so far in 2022: long-term Treasuries via iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT), which has lost 29% this year, which is more than twice as deep as the decline for the US bond benchmark, based on Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Fund (BND).

November, however, has brought relief. Using BND as a proxy for the investment-grade market reflects a strong rally over the past month.

A key driver of the revival in bond prices (and commensurate decline in yields) is speculation that the Federal Reserve is now on a path to start slowing the pace of interest-rate hikes, which in turn implies that a pause and perhaps a reversal for policy tightening is near.

Gregory Faranello, head of US rates trading and strategy at AmeriVet Securities says:

“Fed policy is dynamic and they are still signaling they are going to go higher. But the market trades like it is more comfortable with the Fed getting to an end game.”

Fed funds futures are pricing in a roughly 70% probability for a 50-basis-points hike at the next FOMC meeting on Dec. 14. If accurate, that will be the first downshift from the 75-basis-points increases that have prevailed since the Fed launched the first of a series of hikes in March.

The two-year Treasury yield, arguably the most sensitive maturity for rate expectations, has been flat to lower in recent weeks, providing another clue for thinking that the much-anticipated Fed pivot is close.

The inverted Treasury yield curve also inspires some analysts to think positively on the outlook for Fed policy. The slide in the 2-year/10-year spread, for instance, has plunged to the lowest negative level in decades, which is widely seen as a forecast that a US recession is near.

The inverted yield curve reflects “the market saying: I think inflation is going to come down,” says Gene Tannuzzo, global head of fixed income at the asset management firm Columbia Threadneedle.

The risk is that the Fed’s hawkish policy runs longer and hotter than the bond-market optimists expect. It’s too soon to rule out that possibility. Indeed, New York Fed President John Williams on Monday said that while there’s a clear risk of recession, he also noted that the central bank’s inflation fight could last through 2024.

“Stronger demand for labor, stronger demand in the economy than I previously thought, and then somewhat higher underlying inflation suggest a modestly higher path for policy relative to September,” he said. “Not a massive change, but somewhat higher.”

Although consumer inflation for October suggests the recent runup in pricing pressure has peaked, the Fed will likely be looking for several months of confirmation.

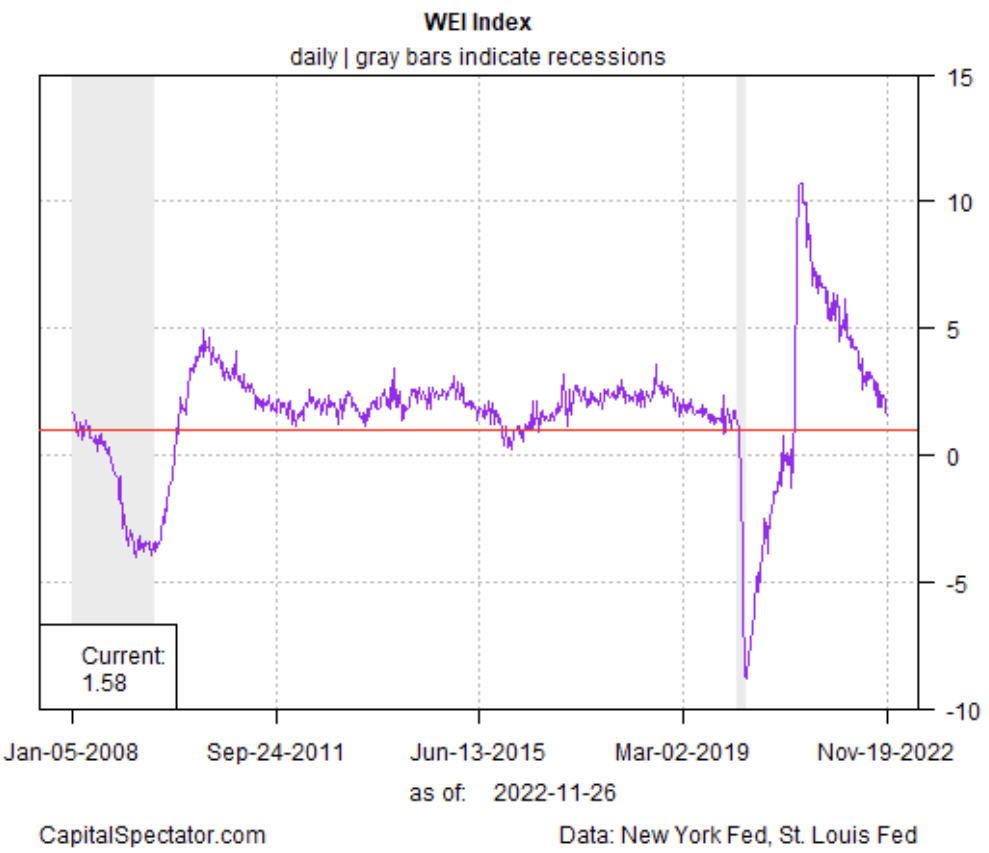

Meanwhile, signs of slowing US growth are accumulating. The New York Fed’s Weekly Economic Index (WEI) fell to a 1-1/2 year as of Nov. 19. WEI is still above a level the indicates recession, but the ongoing slide suggests that the odds of contraction are rising.

That leaves bond traders with the critical question: Will the Fed continue to raise rates if recession risk is marching higher? If the recent rise in BND is a guide, more investors are inclined to answer “no.”