Tyson Foods to close major Nebraska beef plant amid cattle shortage - WSJ

Are markets too confident in a September Fed rate cut? Yes. But are central banks too nervous about another inflation wave? Also, yes, argues James Smith. He’s got a bone to pick this week, as the team looks ahead to a data-fuelled week in financial markets

Why Central Banks Are Wrong About Inflation

Central banks – or some of them at least – seem increasingly worried about another inflation wave. I’m just not that convinced – and let me explain why.

For context, the latest batch of Fed minutes revealed growing concern that tariffs – in theory, a one-off price rise – could feed a much longer-lasting bout of inflation. Here in the UK, the Bank of England’s Chief Economist, Huw Pill, has warned that inflation has a habit of becoming more entrenched once headline CPI rises close to 4% - a level that we’re not far away from right now.

Likewise, in its recent strategy review, the European Central Bank spoke of “upside non-linearities” in inflation, a posh way of reminding us that things snowballed after the 2022 energy price shock in a way that the models failed to predict.

"Central banks are still haunted by the most recent inflation spike"

That, in a nutshell, is the problem. Central banks are still haunted by the most recent inflation spike, which economists everywhere – myself included – failed to predict.

Officials often stress that recent experience has made firms more likely to raise prices in response to a future cost shock and in a more flexible way than they might have done in the past. A change in the inflation mentality, if you like.

The real lesson, though, of the post-Covid inflation spike (and the 1970s for that matter) was that the wider economic context matters enormously. Having a catalyst for prices to rise is one thing. But inflation isn’t going to be long-lasting unless firms have the power to keep passing on higher costs and workers have the power to demand higher wages and protect their disposable incomes.

Pricing power is admittedly quite hard to put your finger on. But it depends a lot on the ability of consumers to absorb higher prices. That ability was bolstered massively by governments back in the pandemic. Remember all those US stimulus checks? And in the aftermath of the Ukraine war, government support propped up consumers here in Europe.

Today, not so much. Not in the US, anyway. President Trump’s tax bill doesn’t represent a major fiscal stimulus, in the sense that the bulk of the tax measures simply extend what’s already in place.

The jobs market story has also changed a lot since the last inflation wave. That surge coincided with an unprecedented shortage of workers and a spike in job vacancies. That’s what enabled workers to drive up wage growth, limiting the downside to their disposable incomes, but also prolonging the inflation wave.

Today, that job market heat has entirely disappeared. In Britain, in fact, the backdrop is looking grim. The scope for wage growth to amplify an externally driven inflation shock has diminished considerably.

It’s all well and good me saying this, of course, but it’s not what I think that matters. For the time being, central banks are genuinely concerned about the risk of inflation taking off again, and I suspect investors may be underestimating that.

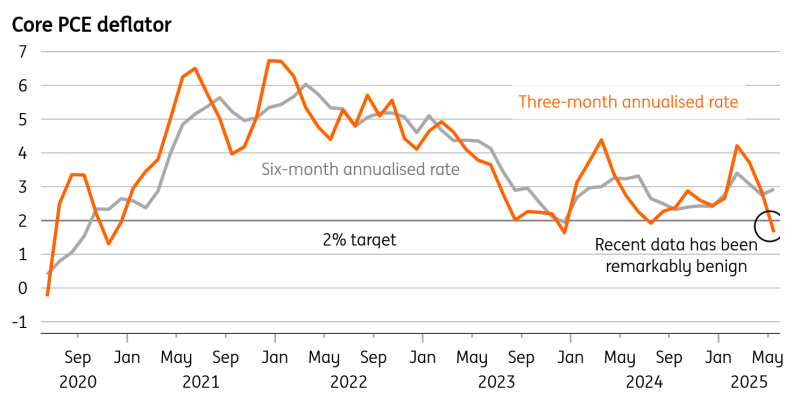

Take the Fed, where markets are pretty confident the Fed will cut rates in September. For that to happen, the recent remarkably benign trend in US inflation needs to continue – something neither we nor the Fed, it seems, thinks we’ll see. Tariffs were always going to hit prices with a lag. And we’re expecting a spike in next week’s core CPI data, as well as chunky rises through the summer as those tariffs take their full effect on goods prices.

That would be big news for markets. My US colleagues expect the US 10-year yield to spike up to 4.75% this quarter, as renewed inflation fears couple with pressure on debt issuance. Our FX team think the prospect of a September cut being priced out could take EUR/USD back towards 1.15 – even if only temporarily.

And temporary is the key word there. This inflation story should be a short-term thing, which means everything I said earlier still holds.

Part of the problem right now is that services inflation – the bit of the inflation basket central banks care most about and tends to be the most slow-moving – is still pretty elevated. But that should start to change.

UK services inflation should come lower in next week’s release, for instance. In the US, weaker consumer demand coupled with falling rents should take the heat out of service-sector inflation as the year wears on. And when that happens, the likes of the Fed and BoE should be much more confident in getting on with the job of cutting interest rates.

That’s it for this week, but before you go, why not join the 400 people already signed up for next Wednesday’s live webinar on all things currencies – including that all-important question: how far can the dollar fall? Sign up here

Chart of the Week: US Inflation Has Been Remarkably Benign Despite Tariffs

Source: Macrobond, ING

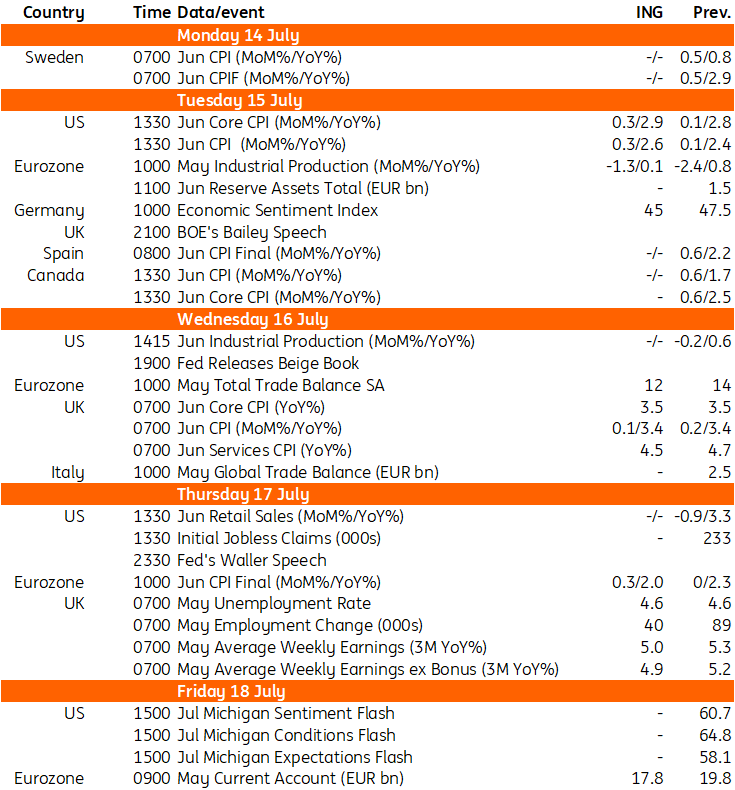

THINK Ahead in Developed Markets

United States

Inflation (Tues): Inflation has been well-behaved in recent months, posting 0.1% and 0.2% month-on-month readings, but we always suspected it would take three months from April/May before the tariffs show up. That means the July, August and September CPI reports are where we will see the more noticeable impact. We expect core CPI to accelerate in Tuesday’s data.

Eurozone:

Industrial production (Tue) and trade of goods (Wed): after strong US frontloading-driven growth for both production and exports in the first quarter, April already saw declines again as frontloading effects faded after “Liberation Day”. For industrial production, April still showed higher levels, though, compared to the January numbers. While new orders have shown some encouraging signs of bottoming out, it does look like April still had a front-loading element driving the level of production higher. The big question is whether the tariff-pause has caused another round of frontloading or whether production and exports data have normalised or even reversed on the back of the higher tariff environment compared to pre-April 2 levels. May data will shed important light on that, also because it will give strong direction on 2Q GDP figures.

United Kingdom (TADAWUL:4280):

- Inflation (Weds): Services inflation is likely to fall back further, and that should give the Bank of England the confidence to cut rates again in August.

- Jobs data (Thurs): Unusually, the jobs numbers look much more significant for markets than inflation next week. Payrolled employee numbers fell at their sharpest rate on record (since 2014), outside of the pandemic, in May. That data may well get revised up next week. But if it doesn’t - and indeed were June’s data to be similarly bad - it would pile the pressure on the Bank of England to accelerate rate cuts.

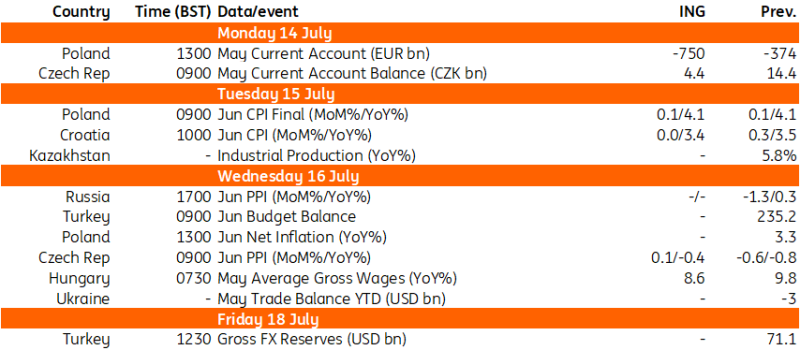

THINK Ahead in Central and Eastern Europe

Poland

- Current account (Mon): Current account deterioration most likely slowed in May. Both exports and imports, in annual terms, were negligible, and the trade deficit was somewhat lower than in May 2024, when it exceeded €1bn. As a result, the 12-month rolling current account deficit probably remained at 0.6% of GDP, broadly unchanged vs. the previous month. The scale of external imbalances remains small despite weak exports.

- CPI (Tue): The StatOffice should confirm its flash estimate of June CPI inflation at 4.1%YoY, but a slight upward revision cannot be ruled out as fuel prices started rising towards the end of the previous month. Still, the overall inflation outlook remains positive and headline should moderate below 3%YoY in July, giving the National Bank of Poland no other option than to continue policy rate cuts. We see the next move in September (no policy meeting in August) and do not rule out a 50bps cut.

Czech Republic

Producer prices (Weds): PPI likely continued its annual decline in June, given demand from the main European trading partners remains tepid and competition is keeping a lid on price increases. Still, the Brent crude spike in the same month made the decline less potent, as it was only partially compensated by a stronger koruna. The current account balance continued to deteriorate in May but likely remained in a slight surplus.

Key Events in Developed Markets Next (LON:NXT) Week

Source: Refinitiv, ING

Key Events in EMEA Next Week

Source: Refinitiv, ING

Disclaimer: This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user’s means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more