Nvidia shares pop as analysts dismiss AI bubble concerns

The CFA Institute trains thousands of financial analysts annually. Yet, its own portfolio follows one of the simplest playbooks: a passive global 60/40 model that hasn’t changed in more than a decade.

Portfolio managers tout their ability to beat the market. Investment consultants design elaborate strategies promising alpha generation. Yet, some of the most sophisticated institutions opt for passive strategies instead, and the CFA Institute is one of them. For an organisation that literally wrote the textbook on active management, it’s an intriguing choice.

The CFA Institute Case: Practicing What It Preaches?

For generations of finance professionals, earning the three letters “CFA” has been a defining achievement, one that ties them to the global community led by the CFA Institute.

Headquartered in Charlottesville, Virginia, the Institute serves more than 200,000 charterholders worldwide and is best known for awarding the Chartered Financial Analyst designation, widely regarded as the gold standard for ethics, competence, and analytical rigour in finance. Its stated mission is to "lead the investment profession globally by promoting the highest standards of ethics, education, and professional excellence."

The CFA Institute is classified as a not-for-profit organisation under Internal Revenue Code § 501(c)(6), which designates it as a business league aimed at improving business conditions rather than a charity. Despite its legal status, it operates like a well-run business, a steady cash-generating machine selling exams, study materials, certifications, and memberships to hundreds of thousands of candidates each year.

These activities produce consistent operating surpluses and, consequently, substantial financial reserves. Because those reserves are backed by strong current assets, they aren’t needed to fund daily operations and can be invested for the long term.

A review of the Institute’s Annual Reports and Form 990s from 2013 to 2024 reveals a remarkably consistent investment philosophy. Its portfolio is managed passively, allocated across low-cost public-market instruments, and can comfortably be described as a global 60/40 model, roughly 60% in equities and 40% in bonds.

The correlation between the Institute’s returns and the BlackRock Global 60/40 ETF (NYSE:AOR) is 0.98, essentially identical. The strategy is passively managed and has remained largely unchanged for more than a decade. No complex derivatives, no hedge funds, no market timing, just broad diversification and disciplined rebalancing.

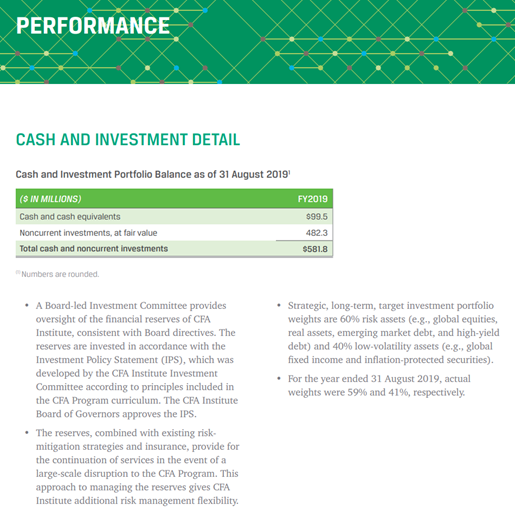

Source: CFA Institute annual report 2019

The few portfolio details disclosed publicly confirm this. Past reports mention Vanguard index funds as core holdings, with no evidence of active management over more than a decade. Each year, the Institute notes that “the reserves are invested in accordance with the Investment Policy Statement (IPS), developed by the CFA Institute Investment Committee according to principles taught in the CFA Program curriculum.” That IPS emphasises discipline, diversification, and cost-efficiency, textbook concepts within the CFA syllabus.

Still, there’s an irony here that’s hard to ignore. The same organisation that certifies thousands of professionals in manager selection and fundamental analysis has chosen to manage its own reserves through the market rather than through active managers.

The 60/40 Portfolio, the Old Faithful

Born out of post-Markowitz diversification theory, the 60/40 portfolio refers to a strategic asset allocation of 60% to equities for long-term capital appreciation and 40% to fixed income for income generation and volatility dampening. The underlying principle is that combining assets with less-than-perfect correlation improves the portfolio’s risk-adjusted return. It is not designed to maximise returns, but to optimise the trade-off between return and drawdown risk.

For institutional investors, the model offers governance simplicity, cost efficiency, and a predictable risk envelope. It limits career risk and behavioural error while providing a defensible benchmark for boards and trustees. In a world where many active strategies underperform net of fees, the 60/40 serves as both a default allocation and a performance hurdle.

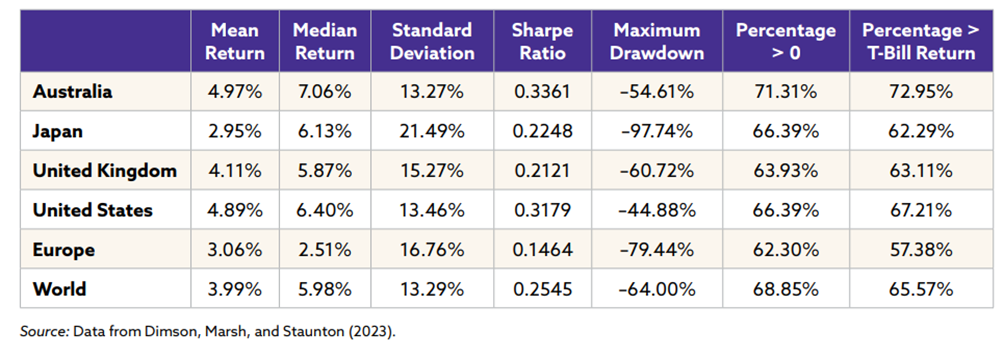

Historically, that trade-off has worked. A US 60/40 allocation has delivered about 5% real annual returns (inflation-adjusted) since 1900, slightly lower in the United Kingdom at just above 4%, and around 3% in Japan and continental Europe. On a global basis, a balanced index proxy such as BlackRock’s AOR ETF has produced real returns around 4–5 % per year over more than a century, with roughly two-thirds of the volatility of an all-equity portfolio.

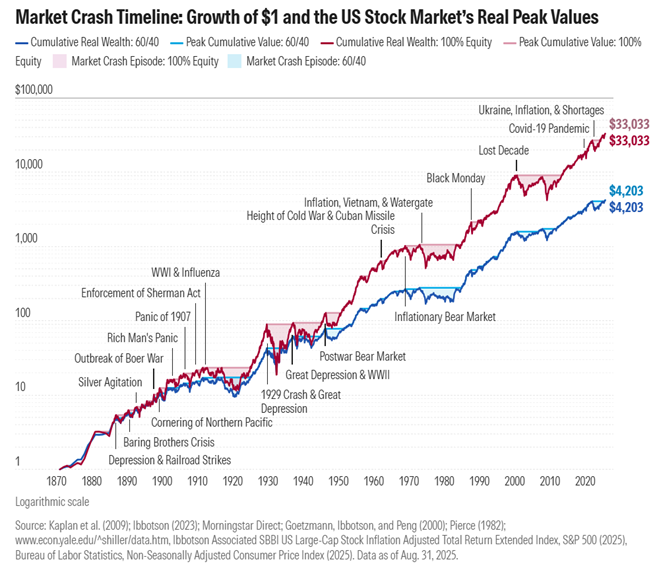

Source: Long-Term Performance of Domestic 60/40 Portfolios in Real Terms, 1901–2022, CFA Institute

However, the durability of the 60/40 portfolio rests less on its upside potential than on its behaviour in market stress. During the Great Depression, US equities fell nearly 80%, but a balanced 60/40 portfolio declined by about 53%, according to Morningstar. In the 2000s, a period often described as the “Lost Decade” for equities, marked by both the dotcom bust and the Great Recession, stocks fell more than 50%, but the 60/40 structure limited the drawdown to roughly 25%. Yet 2022 was one of the toughest years for the 60/40 model.

Both equities and fixed income posted negative real returns, breaking the traditional diversification pattern. The simultaneous selloff led many investors to question whether the classic allocation remains suited in a regime defined by higher inflation and correlated macro shocks. A report from Morgan Stanley Investment Management indicates that a US 60/40 portfolio fell by roughly 17.5% in 2022 before recovering about 17.2% in 2023.

Source: Morningstar

Brian Schroeder of OCIO Monitor analysed the performance of the CFA Institute’s investment portfolio over the period 2013–2024 using data from the organisation’s Annual Reports. Since the institute does not disclose annual percentage returns, Schroeder derived them by dividing the reported total investment gains, interest, and dividends (net) by the beginning-of-year total investments at fair value.

According to his calculations, the CFA Institute’s portfolio delivered a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of roughly 6% over the twelve-year period, with an annualised standard deviation near 8%. Although this performance broadly aligns with a balanced, risk-controlled allocation, it lagged the BlackRock AOR ETF by about 1.3% annually (net of fees). Volatility levels were comparable.

The underperformance stems from allocation differences. The CFA Institute’s portfolio does not replicate AOR’s exact weightings. The split between equities and fixed income shifts slightly year to year, and the underlying holdings are not identical. The 0.98 correlation with AOR confirms a very similar strategy, but not a perfect replica.

The CFA Institute provides limited transparency around portfolio composition and returns and publishes only aggregate figures in its financial statements. This makes independent assessment difficult, still the available data suggest performance broadly consistent with a passive 60/40 allocation

Several explanations can be suggested for why the CFA Institute chooses not to manage its reserves actively. Some see it as an apolitical choice, avoiding any implicit endorsement of specific asset managers. Others argue that a passive, globally diversified 60/40 allocation aligns with the institute’s own principles as a standard-setting body, emphasising long-term consistency over short-term tactical positioning. Brian Schroeder suspects it reflects a quiet acknowledgment that active management in public markets rarely delivers persistent outperformance. Over the past decade, more than 80% of active equity funds and more than 50% of fixed income funds underperformed their passive benchmarks, according to S&P Dow Jones data.

Who Else Went Passive?

The CFA Institute is hardly alone in its embrace of passive management. Large institutional investors, including universities and foundations, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds, are increasingly embracing passive strategies.

Historically, elite endowments like Yale University or Harvard University pioneered the “endowment model” under David F. Swensen: heavy exposure to private equity, venture capital and real assets. But recently that model has come under strain, prompting a reflex toward simpler public-market allocations. For example, recently Yale reportedly planned to sell up to $6 billion of its private-equity holdings. The principal purpose is liquidity management, freeing up cash to ensure operating flexibility in a tighter funding environment, as they face the risk of federal-funding cuts.

The Government Pension Fund Global—Norway’s “Oil Fund”— is another prominent example. Its strategic benchmark index set by the government includes large components of equities and bonds in defined proportions. For example, its management mandate specifies that the equities portion constitutes ~62.5% of the strategic benchmark (with ambition toward 70%) and the fixed income portion the remainder. The fund’s actual allocation at end-2024 was ~71.4% equities, 26.6% fixed income, 1.8% unlisted real estate and 0.1% renewable infrastructure.

Conclusion

Perhaps, the passive 60/40 model removes a particular kind of professional hazard: the need to justify deviations from the market. When performance lags, there are no manager selections to defend, no tactical calls to explain, no fee structures to rationalise. The portfolio simply does what the market does, and for a mission-driven organisation like the CFA Institute, that may be exactly the point. The irony, of course, is that an organisation built on certifying active investment expertise has become one of passive investing’s most credible advocates.