Thursday’s Insider Activity: Top Buys and Sells in US Stocks

- Credit Suisse's difficulties add yet another risk to an already strained European Economy

- The lender's restructuring plans remain uncertain amid persistent solvency concerns

- However, a 2008-type scenario is unlikely as there are many options to avoid the bank's bankruptcy

Credit Suisse (SIX:CSGN) (NYSE:CS), Switzerland's second largest bank, has been in financial headlines in the last few weeks as increasing solvency concerns sparked worries of a Lehman Brothers type of failure in Europe. At the end of Q2, the 160-years-old institution had around 727 billion Swiss francs ($735.68 billion) in total assets.

But while the ticking bomb has just recently caught the attention of the world, Credit Suisse's problems go back a long way, particularly when two of its clients caused it a financial hole with losses of more than $5 billion:

- The bankruptcy of Archegos Capital, a hedge fund.

- The suspension of client funds linked to failed financier Greensill Capital.

The challenges add to the bank's complete lack of direction, with a few of its top executives abandoning the moving ship. As a result, in the first half of this year, CS revealed losses of around $1.904 billion, with Moody's affirming that full-year losses could amount to as much as $3 billion.

The numbers pose a complete change from last year's solid $1 billion H1 performance.

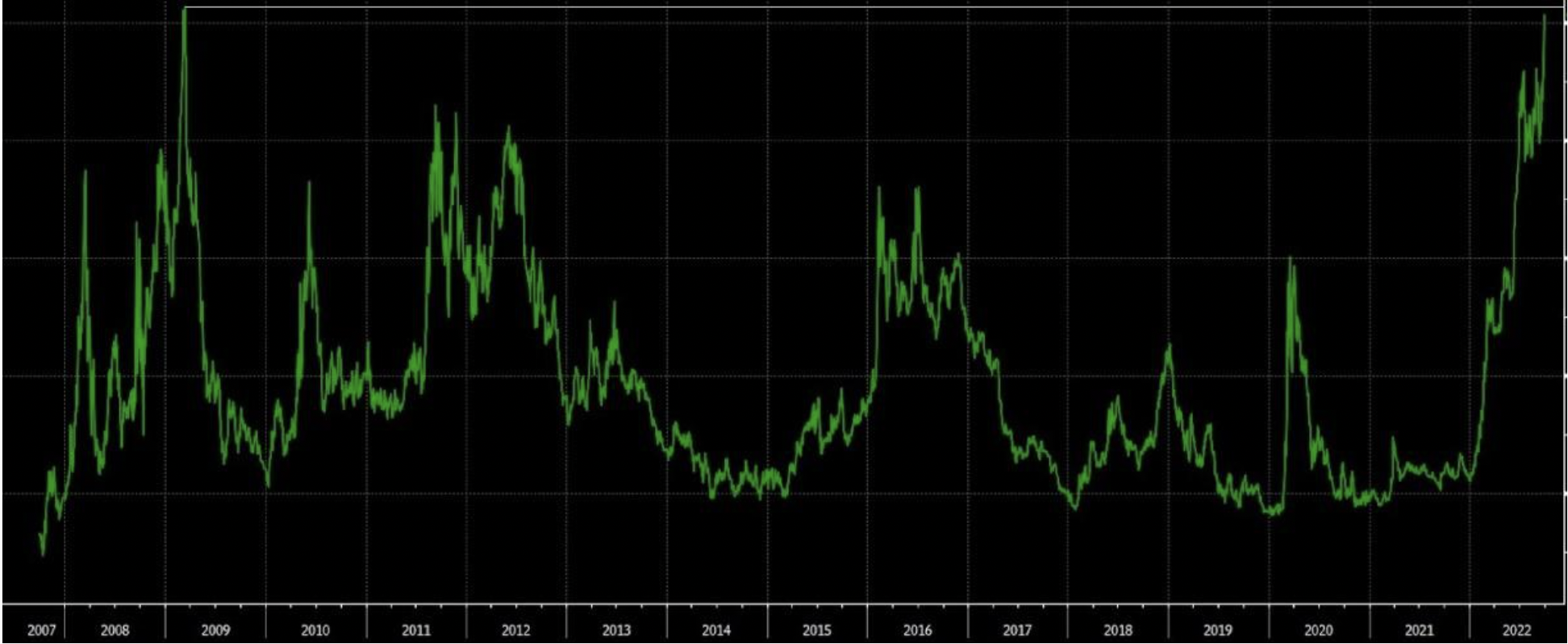

All these factors set off alarm bells about the reliability of the bank's solvency. As proof of this, default insurance, Credit Default Swaps (CDS), rose to record highs (more than 250%).

Source: Bloomberg chart

Credit Default Swaps are a type of insurance against default. Their mechanics are simple: an investor buys a CDS on an asset to hedge the risk of possible default. The investor pays a premium to the seller. If the company goes bankrupt, he will receive the asset's value. If the company does not fail, the buyer loses the premium paid.

But while it is the talk of the town these days, one cannot compare Credit Suisse's issues with 2008. Lehman Brothers was one of the smallest investment banks in the United States, very exposed to the real estate sector, and they let it fall to serve as an example to others.

Unsurprisingly, Credit Suisse shares have been reacting to the headlines, losing around -55% this year. As a result, the bank's market capitalization dropped from $25 billion to around $11 billion.

High net-worth customers proceeded to withdraw their money from the bank, which even caused a queue of transactions and some temporary delays.

Moreover, private bankers initiated a round of contacts and conversations with the most important clients to assure them of the solidity of the bank's capital cushion and liquidity, all in an attempt to prevent the ongoing nervousness from continuing with the outflow of money.

What Happens Next?

All eyes are on October 27, when there are two events:

- CS presents its third quarter results. At the moment, it has two bad quarters in 2022, and the market expects it to close Q3 with a total of $1.7 billion in losses.

- The bank will unveil its roadmap for dealing with the crisis.

CS would need to raise about $4 billion in capital. Everything indicates a possible capital increase to face a profound restructuring of the business and achieve injection of money to avoid the bank's collapse.

The ordinary course of action would be to sell assets to buy time and then proceed with a capital increase. Among the asset sales could be its LatAm Wealth business, excluding Brazil, and cutting its workforce by some 5,000 jobs.

For the time being, Credit Suisse has offered to buy back up to 3 billion euros of its own debt to calm investors. The bank has enough liquidity (its liquidity coverage ratio is one of the highest among European and US banks) to take advantage of the recent fall in the debt markets and buy its own debt at a discount. This caused its shares to rise more than +5% on Friday as the cost of default insurance fell.

It is also considering the possibility of an investor's entry into one of the businesses it hopes to spin off its investment banking business. The aim would be to raise liquidity and finance restructuring costs.

Furthermore, it is also negotiating the sale of a five-star hotel in Zurich for 400 million Swiss francs.

A realistic restructuring plan would indeed go a long way toward calming tempers. The problem is whether we can believe it, as the bank has a history of defaulting on previous restructuring plans.

But the restructuring plan is not the bank's only possibility.

- The Swiss government can rescue Credit Suisse.

- CS could be acquired by another bank; for example, UBS.

- And, of course, bankruptcy, which the market currently gives about a 20% chance of happening.

If the final alternative were to happen, we would have the feared domino effect on the European banking system and a new episode of the financial crisis, which, together with what we are already facing, would be a big deal.

However, it is worth remembering that the Swiss government has already been working since the beginning of the year on a new law that would provide public liquidity support for the country's relevant banks should they fail.

Disclosure: The writer does not own shares of Credit Suisse.