S&P 500 struggles for direction as investor await inflation data

(Bloomberg) -- For the third time in three years Europe is bracing for a storm-driven October as warm Atlantic waters fuel a record-setting hurricane that’s headed toward Ireland and Scotland.

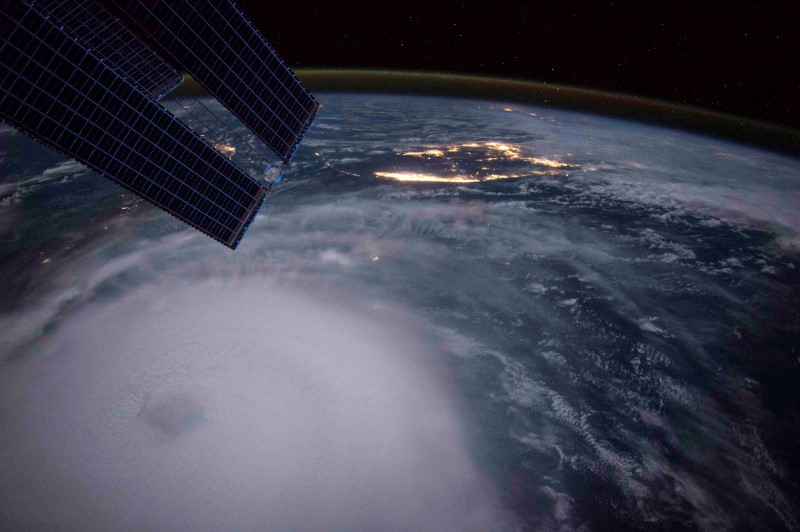

Lorenzo on Saturday became the strongest storm to form in the eastern Atlantic, with winds of 160 miles (257 kilometers) per hour. That made it a Category 5 hurricane, the most powerful level surveyed by forecasters. Since then, the winds have fallen to a mere 100 mph, a Category 2 storm that’s now nearing the Azores.

But as Lorenzo has lost power, it has swelled in size. Tropical storm strength winds reach 345 miles from its center, and 12-foot waves extend out 900 miles. There’s a 50% or higher chance those high winds, accompanied by driving rains, will at least graze Ireland and Scotland, the U.S. National Hurricane Center said.

“This thing is huge,” said Jeff Masters, co-founder of Weather Underground, an IBM (NYSE:IBM) business. “That is a massive wind field and a massive wave field. It is going to cause impacts.”

Winds of at least 74 mph reach out 90 miles in all directions from Lorenzo’s center, said Phil Klotzbach, lead author of the Colorado State University seasonal storm forecast. Based on that metric, it is the largest hurricane ever recorded in the eastern Atlantic, Klotzbach said.

Swells from Lorenzo have spread across the North Atlantic bringing rough surf and rip currents to the U.S. East Coast and Canada as well as Europe and the Caribbean islands, the National Hurricane Center said.

So far this year, the Atlantic has produced 12 storms, the number usually seen in an average season. Two of those storms reached Category 5 strength -- Hurricane Dorian last month, and now Lorenzo. Forecasters are watching two more disturbances near the Caribbean that could become storms. The six-month hurricane season is in its most active phase, and officially ends on Nov. 30.

A warmer Atlantic has fueled the recent spate of storms that have made runs at Europe, allowing them to hold onto their tropical structure and power as they neared a continent not historically known for its hurricane strikes.

In 2017, Hurricane Ophelia became a post-tropical storm as it came ashore near Valentia Island in County Kerry Ireland, killing three people, causing power outages, ripping off roofs and toppling trees. Last year, Hurricane Leslie nearly made it to Portugal before becoming a hybrid storm and flooding France with heavy rains.

The Atlantic’s waters are warmer due to a nasty combination of factors. The ocean undergoes a natural temperature variability over time that forecasters call the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation. At the same time, the effects of global warming are kicking in, said Dan Kottlowski, a hurricane forecaster at AccuWeather Inc. in State College, Pennsylvania.

‘Developing Monsters’

“Thirty years ago there is no way that most of these storms would have come as strong,” Kottlowski said by telephone. “The longer the Atlantic stays warm, the more we will see these monsters developing.”

A similar thing is happening in the Pacific, according to the Weather Underground’s Masters. Hawaii, which for years saw few hurricanes, has been hit, grazed or narrowly missed by an increasing number of storms. In both cases, ocean heat deserves much of the blame, he said.

“This is to be expected if you are going to heat the oceans up,” Masters said. “An extra degree of warming makes all the difference when you are near 80 degrees Fahrenheit, which is the cut off.”