EchoStar stock soars after SpaceX valuation set to double

Investors have been asking themselves when and if we will see a real credit crunch. I think that’s the wrong way to phrase the question. Data shows we are already in a credit crunch.

The real questions to ask are how badly and when is it going to affect the economy and markets.

Let’s try to answer both questions together.

Why so much attention on credit creation in the first place?

A fiat system with weakening demographics and stagnant productivity trends can only achieve acceptable growth levels through the use of leverage: ample and cheaply available credit to the private sector.

When you want to engineer cyclical growth, providing the private sector with cheap credit works like magic.

Even as wages and earnings are unchanged, people can bid up the housing market through cheap and readily available mortgages. Through lower borrowing rates, companies can more easily finance their businesses and engage in more sales.

A lag drives up economic activity, and a virtuous cycle begins cheap credit, strong activity and earnings, buoyant markets, more robust hiring trends, and higher wages.

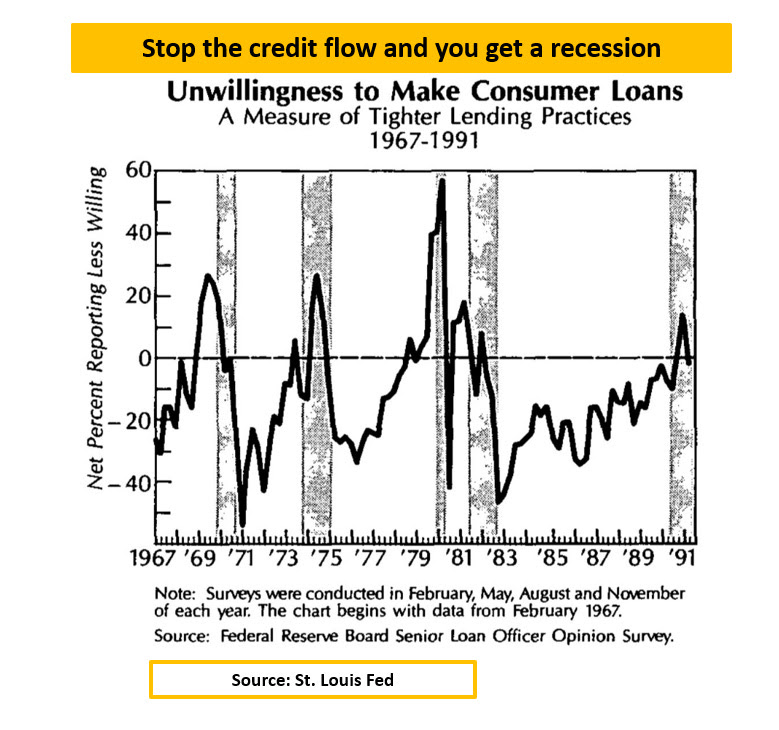

And the opposite happens when the flow of credit dries up, and lending conditions tighten.

This black-and-white chart from the St. Louis Fed shows how this has always been the case, even 60+ years ago: stop the credit flow, and you get a recession (shaded areas).

|

This is why credit data and things like the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS) get plenty of attention in the late stages of the macrocycle – but let’s clear some stuff before we dive into this data.

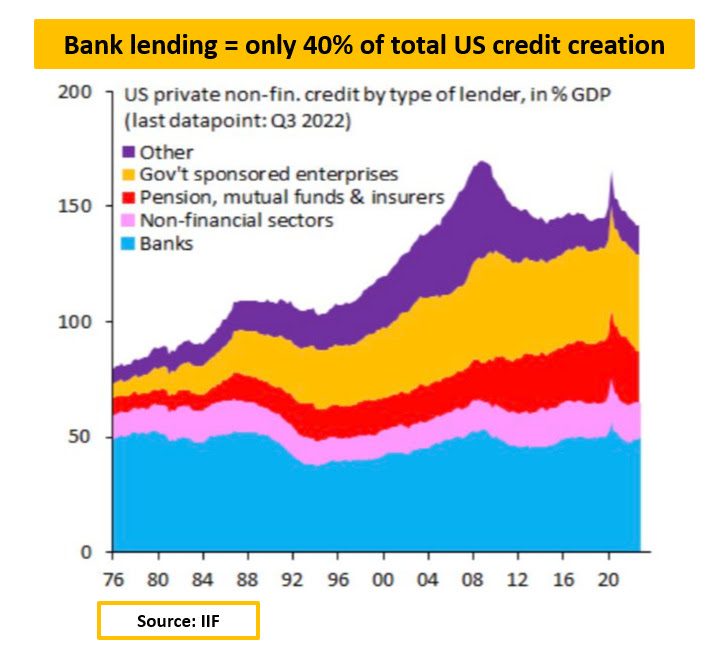

The SLOOS mostly looks at bank lending and demand for bank loans: and while banks are an important driver of credit creation, they are not the only one.

In our highly financialized system, credit creation also happens through capital markets, shadow banks, governments (and gov’t sponsored entities), and through more channels.

In the US, bank lending accounts for only ~40% of total credit creation for the private sector.

To get the holistic look, we developed the TMC Credit Impulse index – a refresh on that metric later.

|

So, you are not looking at the full credit creation picture – but at roughly 40% of it.

The second important point to remember is that the SLOOS asks banks and borrowers whether credit conditions and loan demand have changed relative to the last quarter.

If the net % of banks tightening their credit standards moves from 45% to 40%, it doesn’t mean things are getting better: it means a net 40% of US banks have tightened (again) credit standards this quarter.

0% means banks are applying the same (tight or loose) credit standards as last quarter.

How tight are credit conditions today, and are they likely to worsen?

And when will the economy and markets feel the heat?

***

This article was originally published on The Macro Compass. Come join this vibrant community of macro investors, asset allocators, and hedge funds - check out which subscription tier suits you the most using this link.