Hedge funds are buying these two big tech stocks while selling two rivals

One of the things which alternately frustrates and fascinates me is the mythology surrounding the idea that the central bank can address inflation by manipulating the price of money, even if it ignores the quantity of money.

I say “mythology” because there is virtually no empirical support for this notion, and the theoretical support for it depends on a model of flows in the economy that seem contrary to how the economy actually works. The idea, coarsely, is that by making money dearer, the central bank will make it harder for businesses to borrow and invest and for consumers to borrow and spend; therefore, growth will slow.

This seems to be a reasonable description of how the world works. But this then gets tied into inflation by appealing to the idea that lower aggregate demand should lower price pressures, leading to lower inflation. The models are very clear on this point: lower growth causes less inflation, and more growth causes more inflation.

The fact that this doesn’t appear to be the case in practice seems not to have lessened the fervor of policymakers for this framework. This is the frustrating part – especially since there is a viable alternative framework that seems to actually describe how the world works in practice, and that is monetarism.

The fascinating part is the incredibly short memories that policymakers enjoy when it comes to pursuing new policies using their preferred framework. Here are the simplest of examples: from December 2008 until December 2019, the Fed Funds target rate spent 65% of the time pinned at 0.25%. The average Fed funds rate over that period was 0.69%.

During that period, core inflation ranged from 0.6% in 2010 to 2.4%, hitting either 2.3% or 2.4% in 2012, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019. That 0.6% was an aberration – fully 86% of the time over that 11 years, core inflation was between 1.5% and 2.4%.

Ergo, it seems reasonable to point out that ultra–low interest rates did not seem to cause higher inflation. If that is our most-recent experience, why would the Fed now be aggressively pursuing a theory that depends on the idea that high-interest rates will cause lower inflation? The most recent evidence we have is that interest rates do not seem to affect inflation.

This isn’t just a recent phenomenon. But the nice thing about the post-GFC period is that for a good part of it, the Fed was ignoring bank reserves and the money supply and affecting policy entirely through interest rates (well, occasionally squirting some QE around, but if anything, that should have increased inflation – it certainly didn’t dampen the effect of low-interest rates).

This became explicit in 2014 when Joseph Gagnon and Brian Sack, shortly after leaving the Fed themselves, published “Monetary Policy with Abundant Liquidity: A New Operating Framework for the Federal Reserve.” In this piece, they argued that the Fed should ignore the quantity of reserves in the system and simply change interest rates that it pays on reserves generated by its open market operations.

The fundamental idea is that interest rates matter, and money does not, and the Fed dutifully has followed that framework ever since. As I just noted, though, the results of that experiment would seem to indicate that low-interest rates, anyway, don’t seem to have the effect that would be predicted (and which effect is necessary if the policy is to be meaningful).

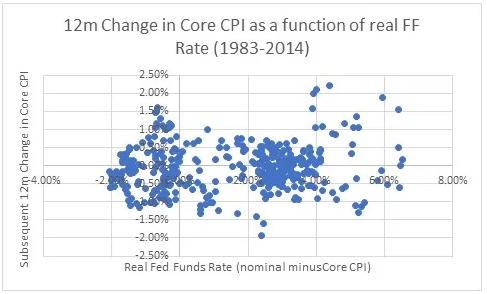

And really, this shouldn’t be a surprise because, for the prior three decades, the level of the real policy rate (adjusting the nominal rate here by core CPI, not headline) has been completely unrelated to the subsequent change in core inflation.

So, to sum up: for at least 40 years, the level of real policy rates has had no discernable effect on changes in the level of inflation. And yet, the current central bank dogma is that rates are the only thing that matters.

I stopped the chart in 2014 because that’s when the Gagnon/Sack experiment began, but it doesn’t really change anything to extend it to the current day. Actually, all you get is a massive acceleration and deceleration in core inflation that happened before any interest rate changes affected growth (seeing as we have not yet had a recession). So it’s a result-within-a-result, in fact.

Any observation about how the Fed manages the price of money rather than its quantity would not be complete without pointing out that the St. Louis Federal Reserve’s economist emeritus Daniel L Thorton, one of the last known monetarists at the Fed until his retirement, wrote a paper in 2012 entitled “Monetary Policy: Why Money Matters and Interest Rates Don’t” [emphasis in the original title].

In this well-argued, landmark, iconic, and totally ignored paper, Dr. Thornton argued that the central bank should focus almost entirely on the quantity of money, not its price. Naturally, this is concordant with my own view, plus more than a century of evidence worldwide that the price level is closely tied to the quantity of money.

To be fair, the connection of changes in M2 to changes in the price level has also been weak since the mid-1990s for reasons I’ve discussed at length elsewhere. But at least money has a history of being related to inflation, whereas interest rates do not (except as a result of inflation, rather than as a cause of them); moreover, we can rehabilitate money by separately modeling money velocity.

There does not appear to be any way to rehabilitate interest rate policy as a tool for addressing inflation. It hasn’t worked, it isn’t working, and it won’t work.