Bill Gross warns on gold momentum as regional bank stocks tumble

No matter what happens, financially or economically, there is always a high number of companies regularly beating Wall Street estimates. Are Wall Street analysts that poor at predicting future corporate earnings, or is there something else potentially going on? Furthermore, what does that mean for investors using those estimates in making investment decisions?

As noted in this article, analysts are always wrong, and by a large degree.

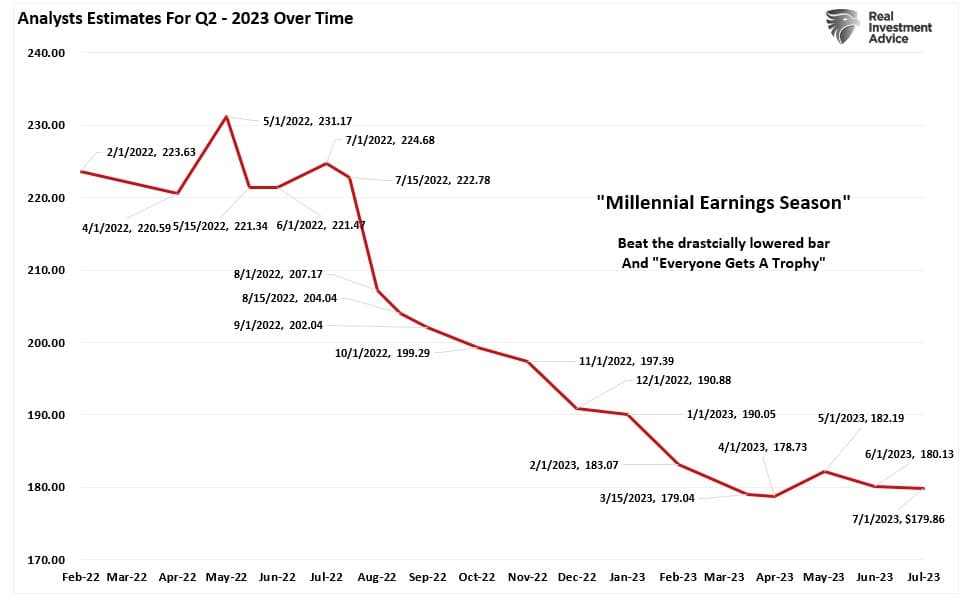

“This is why we call it ‘Millennial Earnings Season.’ Wall Street continuously lowers estimates as the reporting period approaches so ‘everyone gets a trophy.’”

The chart shows the estimated changes for the second quarter of 2023 from February 2022.

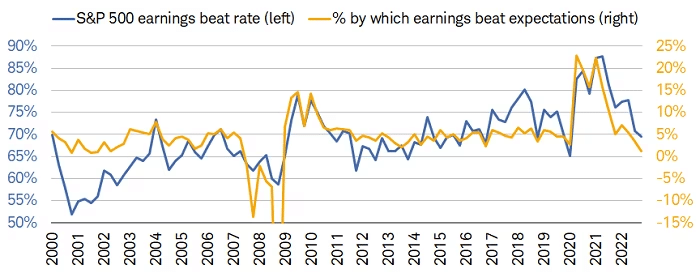

An easy way to see this is the number of companies beating estimates each quarter, regardless of economic and financial conditions. Since 2000, roughly 70% of companies regularly beat estimates by 5%. Again, that number would be lower if analysts were held to their original estimates.

As shown, for companies to win the “beat the estimate game,” they need the bar lowered far enough to ensure they can clear it. If not for these downward revisions in analysts’ estimates, the majority of companies would miss, rather than beat, estimates. Such would obviously weigh on stock price performance which directly impacts executive compensation due to the now standard practice of using stock options.

Read that last sentence again.

Inherent Conflict of Interest

There is an inherent conflict between Wall Street, corporate executives, and individual investors. As stated, there are billions at stake for executives and Wall Street, and the “beat the Wall Street estimate” game is critical in keeping corporate stock prices elevated. Unfortunately, this leads to a wide variety of gimmicks to boost bottom-line profitability, which is not necessarily in the best interest of long-term profitability or shareholders.

In a study by Lawrence Brown, Andrew Call, Michael Clement, and Nathan Sharp, it is clear that Wall Street analysts are clearly not that interested in your financial well-being. The study surveyed analysts from the major Wall Street firms to try and understand what went on behind closed doors when research reports were being put together.

In an interview with the researchers, John Reeves and Llan Moscovitz wrote:

“Countless studies have shown that the forecasts and stock recommendations of sell-side analysts are of questionable value to investors. As it turns out, Wall Street sell-side analysts aren’t primarily interested in making accurate stock picks and earnings forecasts. Despite the attention lavished on their forecasts and recommendations, predictive accuracy just isn’t their main job.”

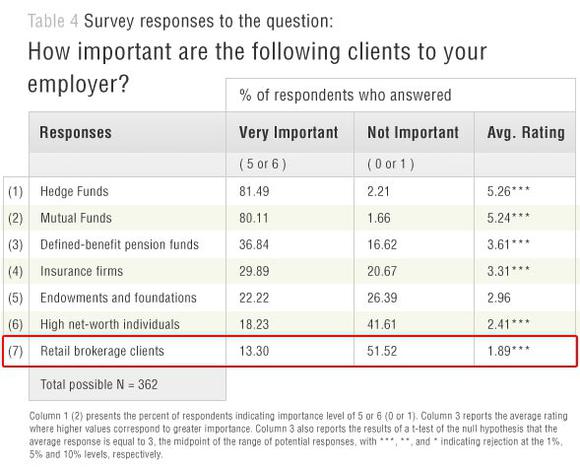

The chart below is from the survey conducted by the researchers, which shows the main factors that play into analysts’ compensation. It is clear that what analysts are “paid” to do is quite different from what retail investors “think” they do.

Sharp and Call told us that ordinary investors, who may be relying on analysts’ stock recommendations to make decisions, need to know that accuracy in these areas is ‘not a priority.’

‘The part to me that’s shocking about the industry is that I came into the industry thinking [success] would be based on how well my stock picks do. But a lot of it ends up being ‘What are your broker votes?’

A ‘broker vote’ is an internal process whereby clients of the sell-side analysts’ firms assess the value of their research and decide which firms’ services they wish to buy. This process is crucial to analysts because good broker votes result in revenue for their firm. One analyst noted that broker votes ‘directly impact my compensation and directly impact the compensation of my firm.’”

The question becomes, “If the retail client is not the firm’s focus, then who is?” The survey table below clearly answers that question.

Not surprisingly, you are at the bottom of the list. The incestuous relationship between companies, institutional clients, and Wall Street is the root cause of the ongoing problems within the financial system. It is a closed loop portrayed as a fair and functional system; however, in reality, it has become a “money grab” that has corrupted the system and the regulatory agencies that are supposed to oversee it.

4 Tools to Win the “Beat the Estimate Game”

However, the analysts are only one-half of the equation. The other half comes from corporations.

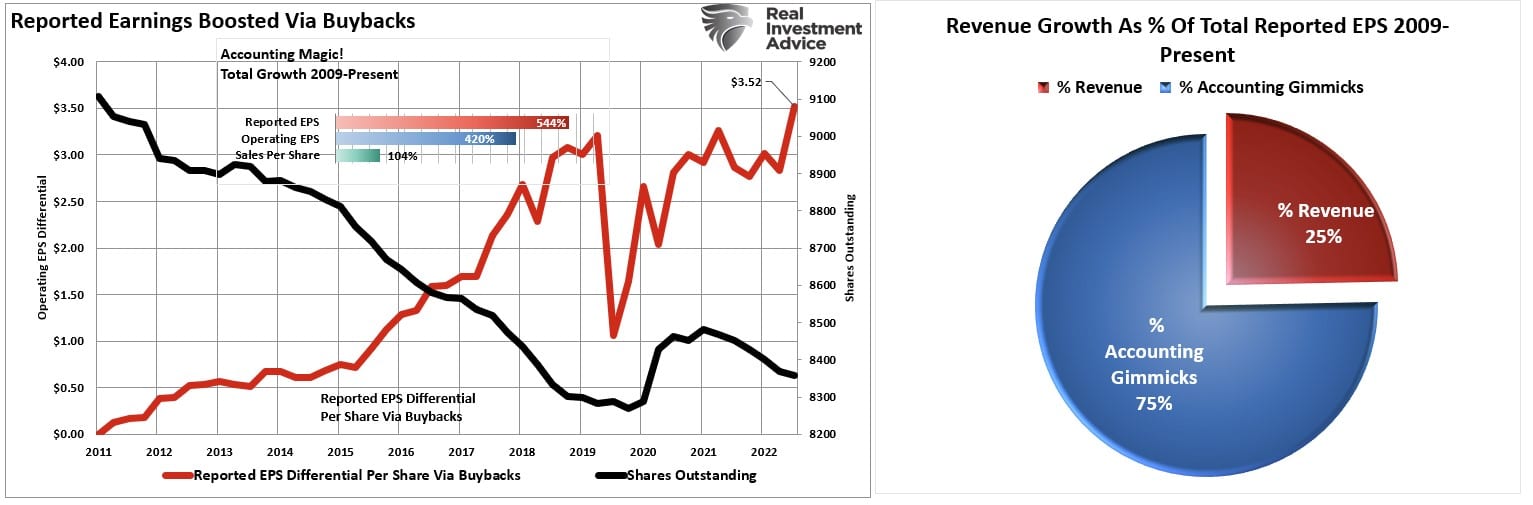

Since 2009, the reported earnings per share of corporations has increased by an astounding 544%. Such is the sharpest post-recession increase in history. However, reported sales per share, which is what happens at the top line of the income statement, has only risen by a marginal 104%.

In order for profitability to surge, corporations have resorted to four primary tools:

- Wage growth suppression,

- Productivity increases,

- Labor reduction via offshoring; and,

- Stock buybacks.

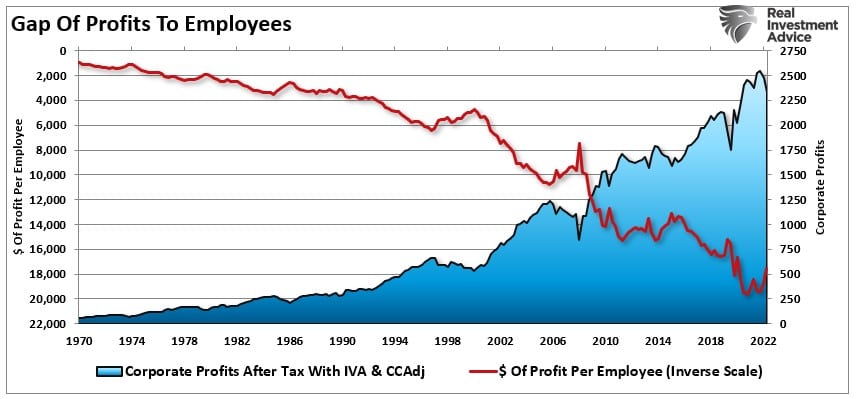

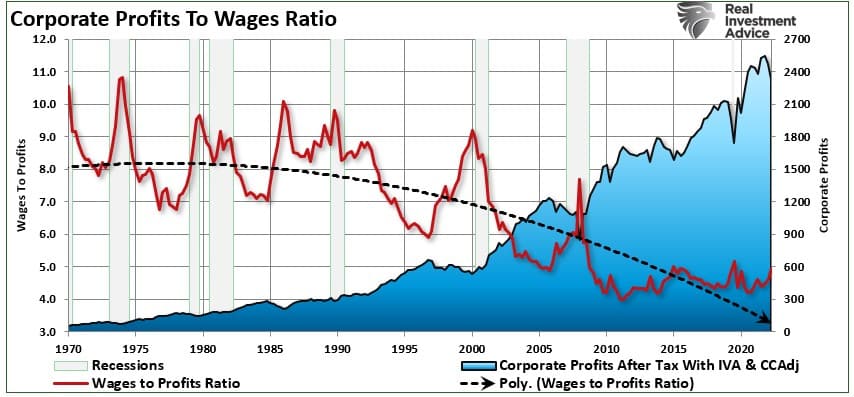

The problem is that these tools create a mirage of corporate profitability. None of these tools increase revenue growth which comes from economic activity. A good way to visualize the issue is the two charts below, which compare corporate profitability to the number of workers and wages.

It is worth noting that when the profits-to-wages ratio starts spiking higher, it historically aligns with economic recessions. Not surprisingly, during recessionary periods, corporations act to protect profitability. They do this by reducing wages and the labor force (the highest costs to any business.) Those cost-cutting measures are supplemented by share buybacks to increase earnings per share for reporting purposes.

The problem with this, of course, is that stock buybacks create only the illusion of profitability. If a company earns $0.90 per share and has one million shares outstanding – reducing those shares to 900,000 will increase earnings per share to $1.00. No additional revenue was created, and no more product was sold; it is simply “accounting magic.”

Such activities do not spur economic growth or generate real wealth for shareholders. However, they boost asset prices to increase executive compensation.

Such is why the “wealth gap” between workers and executives has soared since the financial crisis.

If You Can’t Make It. Fake It?

While Wall Street hopes for an improvement in earnings, there may be more to the story. Many companies have offset earnings growth with cost-cutting measures. The problem with cost cutting, wage suppression, labor hoarding, and stock buybacks, along with a myriad of accounting gimmicks, is that there is a finite limit to their effectiveness.

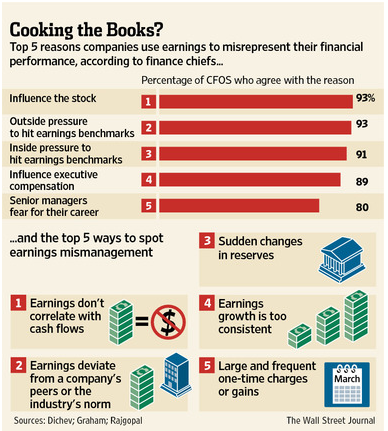

More importantly, Wall Street knows this already, and it should not be surprising that companies manipulate bottom-line earnings. By utilizing “cookie-jar” reserves, heavy use of accruals, and other accounting instruments, they can either flatter or depress earnings.

“The tricks are well-known: A difficult quarter can be made easier by releasing reserves set aside for a rainy day or recognizing revenues before sales are made, while a good quarter is often the time to hide a big “restructuring charge” that would otherwise stand out like a sore thumb.

What is more surprising though is CFOs’ belief that these practices leave a significant mark on companies’ reported profits and losses. When asked about the magnitude of the earnings misrepresentation, the study’s respondents said it was around 10% of earnings per share.“

As I stated at the beginning, the reason that companies do this is simple: stock-based compensation. Today, more than ever, many corporate executives have a large percentage of their compensation tied to company stock performance. A “miss” of Wall Street expectations can lead to a large penalty in the company’s stock price. It is unsurprising that 93% of the respondents pointed to “influence on stock price” and “outside pressure” as reasons for manipulating figures.

Note: For fundamental investors, this manipulation of earnings skews valuation analysis, particularly with respect to P/E’s, EV/EBITDA, PEG, etc. Revenues, which are harder to adjust, may provide truer measures of valuation, such as P/SALES and EV/SALES.

Conclusion

So, as we delve into the Q2 earnings season, we must remain aware of what is real and what isn’t.

To win the “Beat The Estimate Game,” focus on the quality, rather than the quantity, of earnings. As was pointed out previously by the WSJ:

“First and foremost, investors should keep an eye on cash flow: Strong earnings when cash flow deteriorates may be a sign of trouble. The advantage of this approach is that, unlike some of the other warning signs, it is easily measurable, arming the investors and analysts who do their homework with strong ammunition against management.

Secondly, stark deviations from the earnings recorded by the company’s peers should also set off alarm bells, as should weird jumps or falls in reserves.

The other potential problem areas are more subjective and more difficult to detect. When, for example, the chief financial officers urge stakeholders to be wary of ‘too smooth or too consistent’ profits or ‘frequent changes in accounting policies,’ they are asking them to look at variables that don’t necessarily point at earnings (mis)management.”

As the quarterly ritual of earnings season proceeds, we would do well to remember the words of the then-chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Arthur Levitt, in a 1998 speech entitled “The Numbers Game.”

“While the temptations are great, and the pressures strong, illusions in numbers are only that—ephemeral, and ultimately self-destructive.”

Couldn’t have said it better myself.