The recent news is clearly about the imposition of new reciprocal tariffs on US trading partners and the responses that those countries will have to the tariffs. In terms of the markets’ reactions, it does seem shocking to me that people were shocked and appear to have not been particularly well hedged considering that the Administration has clearly been telegraphing this action for a long time.

For what it’s worth, expect the countries with big surpluses to the US (they sell us a lot more than we sell them) to rapidly cut their trade barriers while countries that are closer to balance in their flows to beat the drum more. But there is a ton of analysis out there about the tariffs, most of it informed by bad modeling, and I have already expressed my view that this is going to (a) have a smaller price impact in the US than most people are worried about, (b) may produce a technical recession simply because of all of the front-running imports we have seen in Q1-Q2, (c) will increase, not decrease, US employment, although it (d) may well result in longer recessions ex-US. Oh, and furthermore (d) will tend to result in lower global energy prices, which will help further with (a).

Today, though, I want to talk about another policy that is going to work the other way on inflation but no one else I have seen has mentioned this yet. And that is how the sharp decrease in federal appropriations going to colleges and universities is going to lead to a sharp acceleration in tuition inflation going forward, especially if the stock market continues to decline.

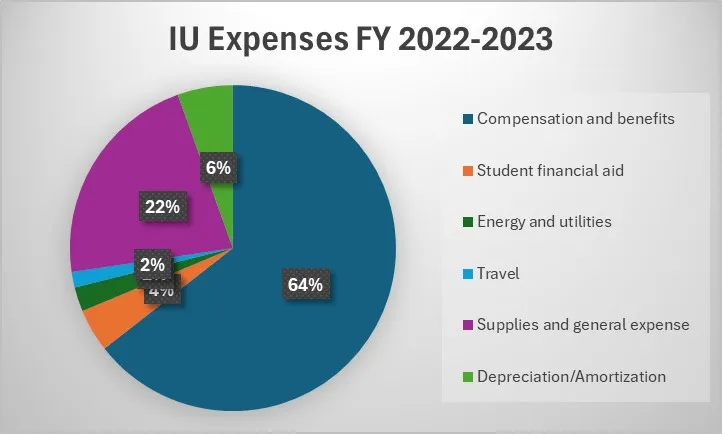

To understand why, consider a simple but descriptive model of how college tuitions are set. Colleges have fairly simple income statements in aggregate: expenses are primarily labor, along with ancillary expenditures on physical plant and other expenses, while revenues consist of tuition, government funding (in the case of public institutions), and endowment earnings (primarily in the case of private institutions). For the purposes of illustration, I randomly pulled the annual report of Indiana University. The tabular numbers are on page 23, but here they are graphically.

So, as I said, compensation expenses are 2/3 of the budget and revenues are half tuition, and another 20% federal grants and contracts (and a little bit from state and local). Some of the ‘auxiliary enterprises’ or ‘other revenues’ may be endowment returns, but those tend to dominate more at private institutions. Either way, Note that the Board of Trustees has no control over endowment returns or government appropriations, even if they have nominal control on some of the other levers. Also, the Trustees have very limited control, especially in the short-term, on compensation and benefits – it isn’t like you can fire your tenured professors and go get cheap ones. So, in practice, the university budget is balanced on the one number the Trustees really do control in the short run, and that is tuition.

So expenses are fairly inflexible and highly driven by inflation (since wages follow inflation). That means that tuitions also increase faster, obviously, when the general level of inflation is faster and vice versa. But on top of that, tuitions tend to increase more slowly when governments are pitching in more (or endowment returns are awesome), and more quickly when governments are pitching in less (or endowment returns are weak). Here is our model, set against an index of tuition from 4-year public universities.

The model simply uses the College Board’s information on government appropriations per FTE student from the same report, along with simple equity returns, bond yields, and inflation. The little deviation at the end is interesting in itself because it happens starting at COVID, when tuitions went up less than the model would have expected. Or did they? I wrote at the time that the BLS was assuming no quality adjustment downward despite the fact that many schools were quasi-virtual or fully virtual. That’s an issue – our model also assumes no state change in the quality of education during the COVID years – but other than that, the model worked pretty well.

The point is that a decrease in federal appropriations will result in a large increase in expected tuition inflation. The betas on our model are not helpful, because they assume a homoscedastic relationship…that is, the effect of changes in that variable (beta) does not change with the size of the change in the variable. That seems unlikely here. If federal appropriations per student drop 10%, I feel reasonably confident that we have the scale of the impact right. If they drop 50%, I suspect states will pick up some slack, tuitions will jump, schools will try to cut costs (for a change), flush more from the endowments, and take some financial lumps. But tuition would still experience a really sharp jump in that case.

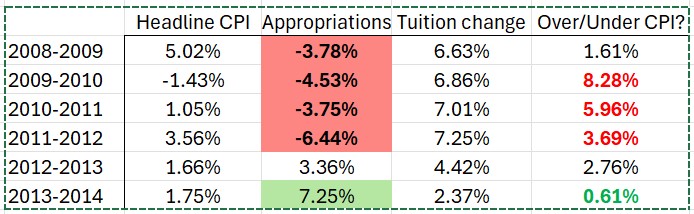

For scale, consider the following table. In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (when admittedly endowments were also in bad shape…it turns out to be a little hard to disentangle those two highly-correlated effects), appropriations for education declined for four years in a row (red cells). Even though inflation overall during that period declined from 5% to -1.4%, and then 1.1%, 3.6%, and 1.7%, tuition inflation actually accelerated from 6.6% to 7.25% before finally decelerating a bit. In the 2013-2014 school year, when appropriations rebounded, tuition rose only 0.6% faster than headline CPI.

Now take those -4% appropriations changes and turn them to -30%. The model says that should give us something like 15% tuition inflation year/year. That seems unlikely to me, and even more unlikely the larger those appropriation declines are. Because colleges will adapt, or close. In the medium term, the result will be higher tuitions, lower college services (what? No NIL money for the football team? No all-you-can-eat sushi?), tighter operating budgets and fewer ancillary staff. And lots of people will discover they are ancillary staff. In the short term, it is hard to judge the scale (partly because we really don’t know how much federal aid will decrease). I am comfortable, however, with the direction. College tuition inflation is about to accelerate, and probably a lot.