Jamaica’s outlook revised to stable by Fitch after hurricane

The early growth of Bitcoin and the cryptocurrency space was originally stimulated by the mistrust of centralized control of monetary policy and financial institutions. While Bitcoin is a fiat currency, in the sense that it is not ‘backed’ by anything and has value only because other people believe it has value, the rules for the expansion of the total float of Bitcoin are mechanical and so the unit benefits from being isolated from the whim of flesh-and-blood central bankers.

Milton Friedman once said in an interview with the Cato Institute that:

“We don’t need a Fed…I have, for many years, been in favor of replacing the Fed with a computer [which would, each year] print out a specified number of paper dollars…Same number, month after month, week after week, year after year.”[1]

And, with Bitcoin, that is exactly what you have. Management of Bitcoin is decentralized, automatic, and the rules are stable.

Unfortunately, ‘fiat’ cryptocurrencies are anything but stable. Moreover, since their value depends entirely on the trust[2] of other actors in the economic system that these currencies will have value, it is entirely possible that any of them could crash just like any fiat currency sometimes crashes when confidence in the currency issuer vanishes. There is no intrinsic value to a fiat currency – digital, or analog – which means that they are stable only when looked at in a self-referential frame. A US Dollar has a stable value of $1 but is volatile from the viewpoint of a Mexican-peso-based observer. I will return to this observation presently.

Because these fiat cryptos are unstable when looked at by a participant in the analog world, the concept of ‘stablecoin’ was developed. In Coinbase’s summary ‘What is a stablecoin?’, the first two bullet points are:

- Stablecoins are a type of cryptocurrency whose value is pegged to another asset, such as a fiat currency or gold, to maintain a stable price.

- They strive to provide an alternative to the high volatility of popular cryptocurrencies, making them potentially more suitable for common transactions.[3]

Why is a stable price important? The answer goes back to the question of whether Bitcoin and similar cryptos are money, or assets. In the conventional definition of money, such a label only applies to units that provide a medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account. First-generation cryptos certainly serve as a medium of exchange but are sketchy on the ‘store of value’ and ‘unit of account’ dimensions. Nothing natively is priced in BTC, so it is not a good unit of account, and the high volatility creates a high barrier to any argument about being a store of value. Cryptos are most assuredly financial assets. It is hard to argue that they are money.

Enter the stablecoin. By pegging the value to an existing currency, a stablecoin ‘borrows’ the characteristics of that currency as a store of value and unit of account. It’s true by mathematical association: if USDC is equal to one US dollar, and the US dollar is money, then (as long as it’s accepted a medium of exchange) USDC is money because it has equal ‘store of value’ and ‘unit of account’ dimensions.[4] A stablecoin maintains its stability by means of holding reserves and being fully convertible on demand into the underlying currency.[5]

But Stable with Respect to What?

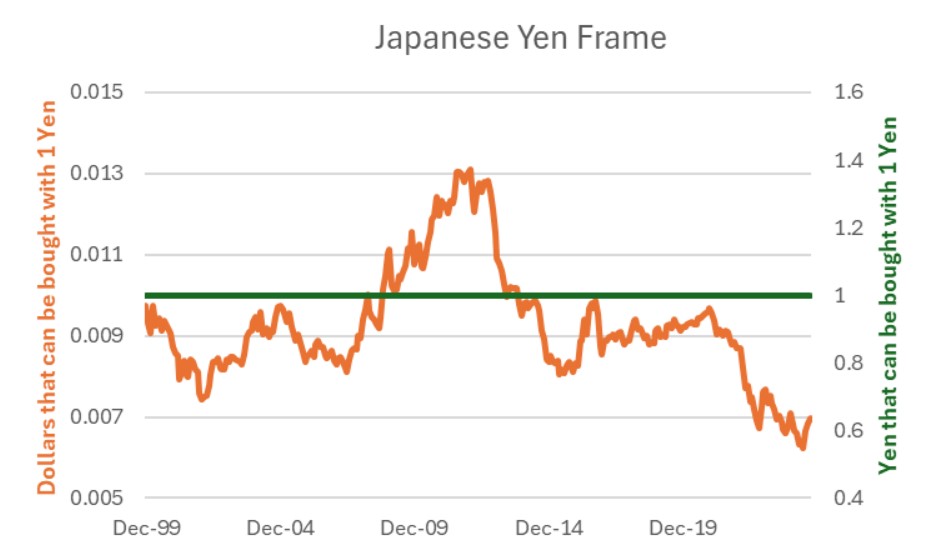

Stability, though, depends on the frame of reference. Consider a stablecoin linked to the US Dollar, which always can be minted or burned at $1 (ignoring fees). Consider a second stablecoin linked to the Japanese Yen, which always can be minted or burned at ¥1. Which one is stable?

The answer, of course, depends on your frame of reference. From the standpoint of someone in Japan, who is buying goods and services with Yen, a stablecoin like USDC that is linked to the dollar is most assuredly not stable in any useful sense of the word. Conversely, a US dollar investor would not find a Yen stablecoin to be stable. This, then, is an important element of defining a stablecoin: something which matches the volatility and behavior of the basis of the frame you are in, is stable with respect to you. This raises an interesting question when it comes to stablecoin regulation. A coin could very easily be regulated as a stablecoin in one jurisdiction, and not be regulated as such in a different jurisdiction – even between regulatory jurisdictions that are congruent in their treatment of most assets.

What passes for stability, in short, depends on the transactional frame – literally, the underlying currency in which transactions happen – of the observer.

Stable with Respect to When?

The meaning of stability also fluctuates with the time horizon of the observer. Fixed-income investors are very familiar with the concept of Macaulay duration, which is the future horizon at which the value of a bond holding is completely insensitive to parallel shifts in the yield curve, because the change in the value of reinvested coupons (which goes up with higher interest rates) exactly offsets the change in the value of the remaining cash flows (which go down with higher interest rates). What is the riskiness of a bond with a 7-year duration? Or more to the point of this discussion – which is riskier, a 1-month Treasury bill, or a 7-year zero coupon bond?[6]

As it turns out, it depends on the applicable horizon of the observer.

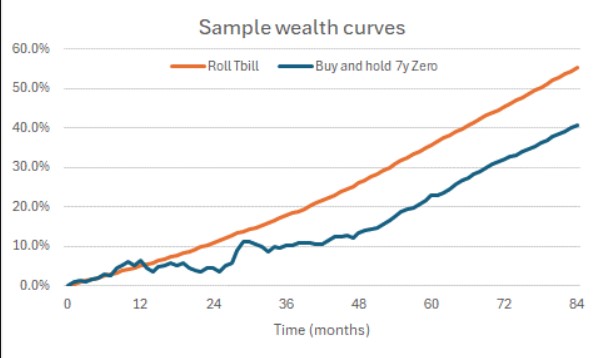

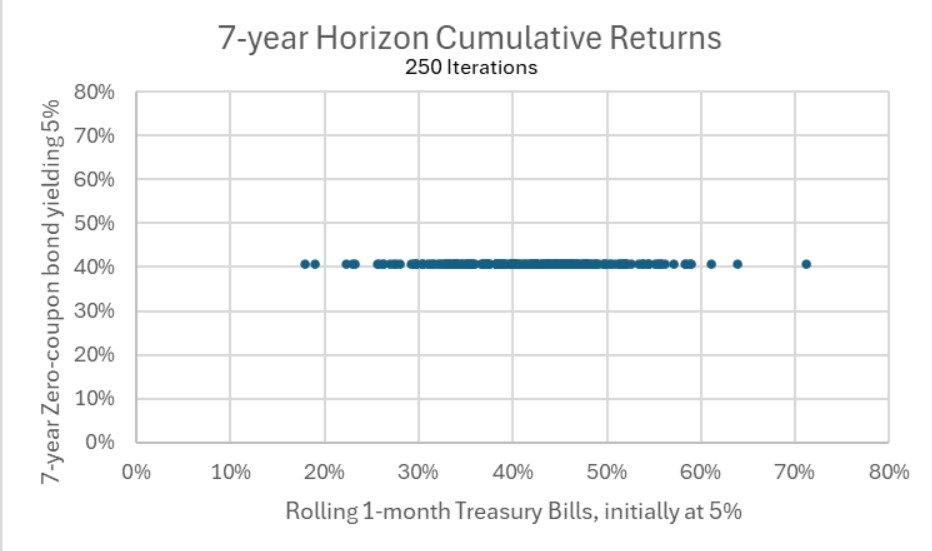

Suppose an investor pursues one of two strategies: in the first strategy, he or she buys a 1-month Treasury bill, initially at 5%, and then rolls the proceeds every month for 7 years. Alternatively, he or she could buy a 7-year zero coupon bond yielding 5%. Using a simple two-factor model with no drift, I generated 250 iterations of T-bill paths and yield curve shapes, to produce hypothetical monthly time series of returns for the two strategies. For example, here is one such random path (Figure 3):

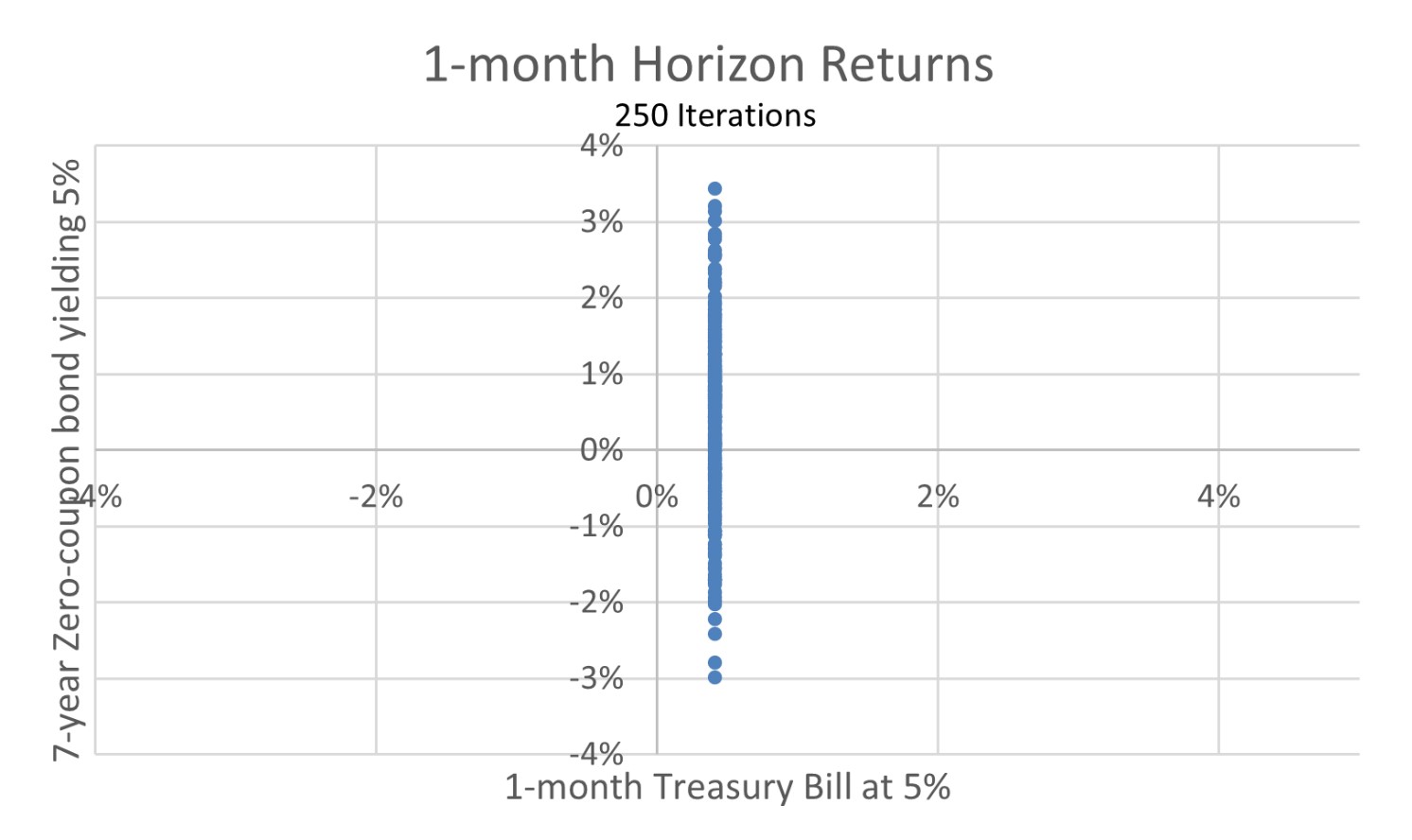

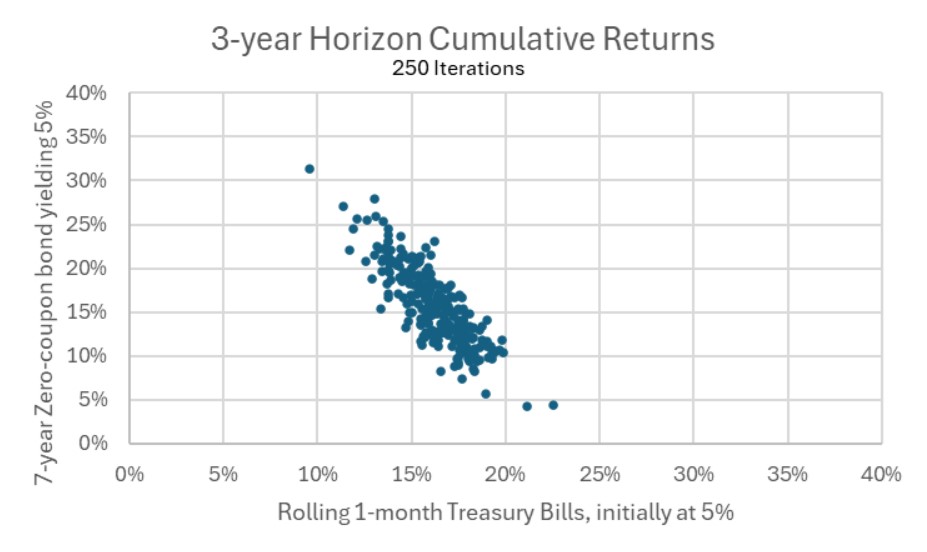

The a priori expected return is approximately the same for both strategies; sometimes the T-bill roll strategy ends up ahead and sometimes the buy-and-hold strategy wins. With similar expected returns, a rational investor would therefore choose the one which has the lowest risk. But the riskiness or stability of the returns depends very much on the observer’s time horizon. Each of the following three charts is drawn from the same 250 Monte Carlo iterations, but the cumulative return is sampled at a different horizon. In Figure 4, the cumulative returns are sampled at the 1-month horizon. In Figure 5, the sampling is at the 3-year horizon. In Figure 6, the sampling is at the 7-year horizon. For each figure, the cumulative return for the T-bill strategy is shown on the x-axis and the cumulative return for the zero-coupon-bond buy-and-hold strategy is on the y-axis.

Although this conclusion is trivial and inevitable to fixed-income investors, the reason for our observation here is to point out that what is considered ‘stable’ not only depends on one’s functional currency but also on one’s holding period horizon.

Is the Nominal Frame the Most Important Frame?

The prior points are likely obvious to most investors. If you are investing with the intention of spending the proceeds in US Dollars, then a USD frame is most relevant. If you are investing for a known future nominal payout (for example, a life insurance company hedging scheduled annuity flows), then an investment that matures to a given value at the time when the money is needed is the most-relevant frame. However, investors sometimes lose track of one of the most important frames, and that is the “real” frame where values track the price level.

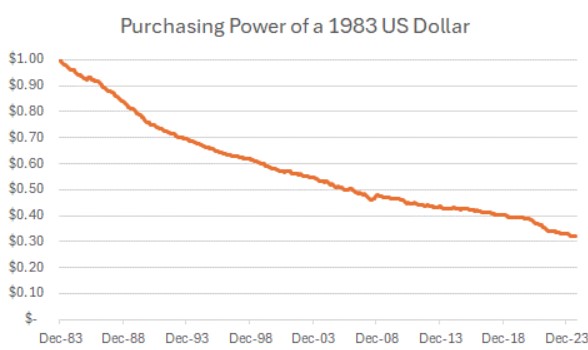

While a $1 bill is ‘stable’ in nominal terms – it will always be worth $1 – it is very unstable in purchasing-power terms.

The framework where we ignore the value of the dollar, in preference for the fixed price of the dollar at $1, is the “nominal” framework. When inflation is low and stable, this frame is a useful shorthand in much the same way that when traveling abroad a tourist in the year 2000 might translate Mexican Peso prices into US Dollar prices by dividing by 10 even though the exact exchange rate differs from 10:1. In the short term, such a shortcut framework makes up for in convenience what it surrenders in precision. But in the long term, what starts out as mild imprecision becomes wildly inaccurate as the Peso exchange rate has gone from 10:1 to 20:1.

Similarly, while the nominal frame is the default for short-term comparisons it is clearly not the most important one to a consumer. Someone who is negotiating a salary at a new job, who knows he or she made $40,000 per year in 2004, would be ill-suited to use that figure as the starting point. The frame that matters over time is the real, or inflation-adjusted, frame. In the chart above, if we plotted the purchasing power of an inflation-adjusted 1983 dollar, it would be a flat line at $1.[7] On the other hand, if we plotted the nominal value of that same inflation-adjusted 1983 dollar, it would show a mostly steady increase from $1 to $3.15 over the same time period.

As before, the frame matters. A dollar that is stable in nominal space is very unstable in purchasing-power space. A unit that is stable in purchasing-power space looks unstable in nominal space.

If an investor or consumer had to choose one frame to care about, it would surely be the one in which his or her money represents not just a medium of exchange and a unit of account, but also a store of value. What this means is that a coin that is native currency and inflation-adjusted in the local price level is the most stable of stablecoins. And what that further implies is that what we currently call ‘stablecoins’ are stable only in the narrow context of being fixed at a certain nominal value of domestic currency…and that is suboptimal since all investors and consumers live in a world where prices change.

Tying Frames Together

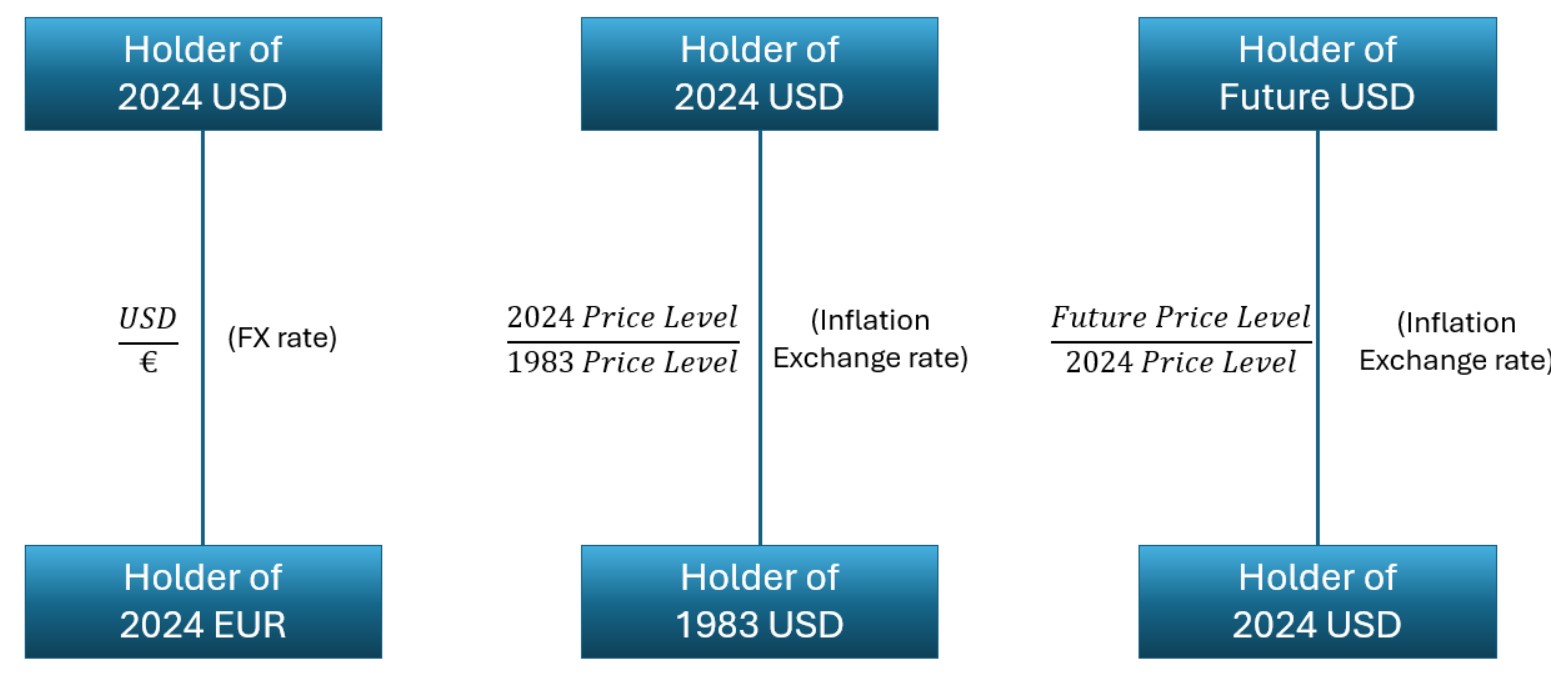

What is interesting is that each of these frames describes “stability” in a different context. People in one frame see their own side as stable and the other side as volatile – and the exact same thing is true, in reverse, for the other side.

The various frames do traffic with each other. A holder of US Dollars (in the nominal-USD-short-term-stable frame) exchanges those dollars with a person who holds Euros (in the nominal-Euro-short-term-stable frame). We call that an exchange rate. And what ties together the nominal dollar and the inflation-linked dollar is the price index.

Figure 8 – Exchanging dollars with different purchasing power is functionally the same as exchanging currencies with different purchasing power

In fact, the relationship between the Dollar and the Euro is so much like the relationship between the nominal dollar and the inflation-linked dollar that in 2004 Robert Jarrow and Yildiray Yildirim wrote a paper describing how to value inflation-protected securities and derivatives using a model designed for foreign exchange.[8] And that highlights the fact that an inflation-linked stablecoin isn’t some strange construct but rather an important new product to be added to the cryptocurrency universe. It is just another currency – one that is fixed in time, rather in nominal dollars, that is exchangeable to today’s dollars at the ‘inflation exchange rate’. If a 1983 dollar existed today, it could be exchanged for $3.15 current dollars because the dollar that was frozen in time in 1983 buys more than today’s dollars. That’s just an exchange rate!

Conclusion

It seems that ‘stability’ is not a stable term. Perhaps a more accurate description of the current crop of ‘stablecoins,’ which are exchangeable 1:1 with the base currency, is “fixed coins.” Only an inflation-linked coin would be a “stablecoin” in the true sense of the word, and only because being stable in purchasing-power space is the most important frame.