European stocks mixed on Friday after volatile week; U.K. economic woes

A subscriber wrote to me recently and asked about a research piece put out by a major sell-side investment house that discussed how private rental indices (such as Zillow and the Fed’s NTRR (“New Tenant Rent Index”, as defined in a paper by the Cleveland Fed’s Randall Verbrugge a couple of years ago called “Disentangling Rent Index Differences: Data, Methods, and Scope”) were indicating that a decline in rent inflation was on the way.

I felt like it was time for an update on this topic, since it has been a little while since the exact same arguments made the rounds a few years ago.

I even had a podcast (Ep. 74: Inflation Folk Remedies) in July 2023 in which I discussed (among other things) the NTRR issue. So the deceleration of Zillow and the other private rent indices, the NTRR, which was forecasting sharply negative rent growth (before revisions!), the supply of new rental units – all of those are arguments from 2023!

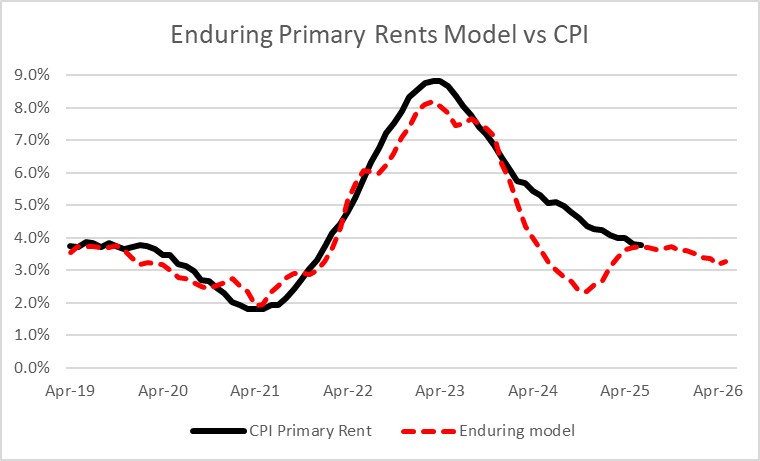

Here are the rents. The black line is the actual CPI for Primary Rents, y/y. In July of 2023, it was at 8%. You may notice that it never went negative in 2023 or 2024, and isn’t showing any signs of going negative in 2025.

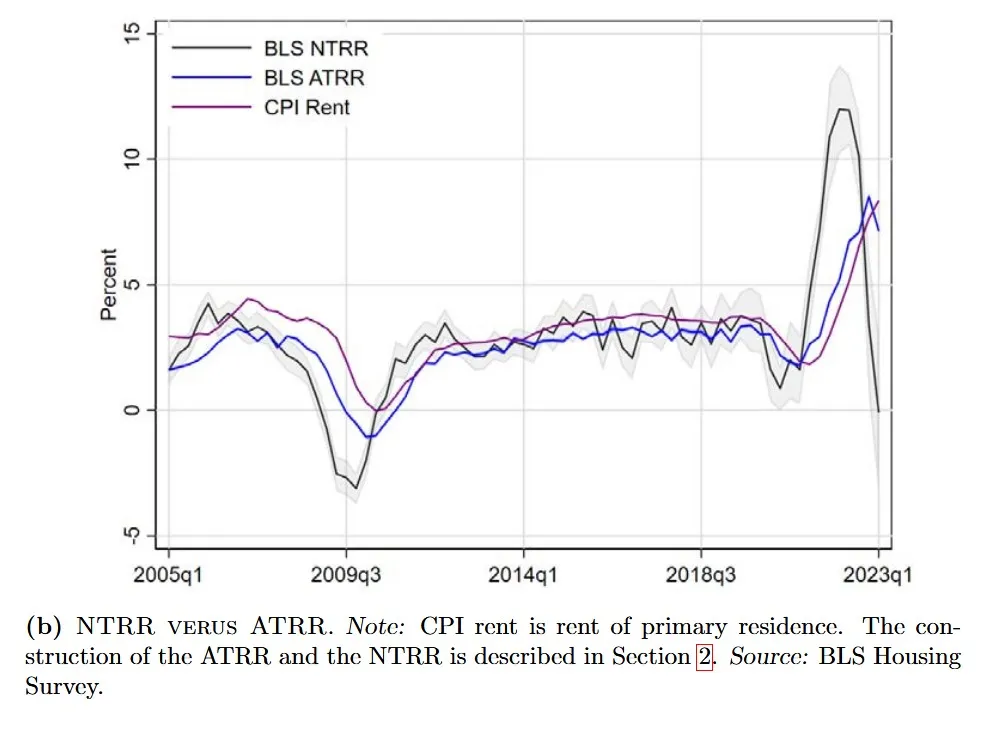

Before I go any further, here is a sufficient reason to ignore the NTRR, in addition to the other arguments I’ll make in a bit. Here is the chart of the NTRR from the 2023 paper.

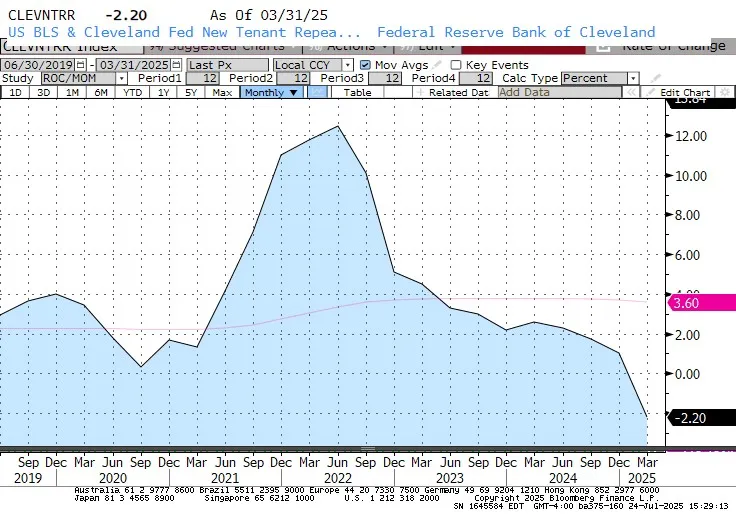

And here is the updated NTRR from Bloomberg today. You will note that the 0% print in 2023Q1 from the 2023 paper has been revised up to around 4.5%. That’s even higher than the upper edge of the error range in the prior chart.

So forgive me if I don’t panic at the -2.2% current reading of the NTRR. Here’s the problem: the conviction among economists in 2023 (not just the Fed economists, but it was a general consensus at the time that rents were about to collapse) that the “stock” of rent inflation would eventually respond to the “flow” of new rents is just not how rents work. The new rents are not indicative of new conditions, while the stock isn’t…those are two totally different populations.

There are people who turn over rents and move with some frequency, or who are moving now for one reason or another, and there is a stock of open units that landlords want to fill. But just because a landlord offers a low rent to fill his one open unit has nothing to do with his desire to cut rents on all of the units that aren’t turning over.

What is amazing is that the only reason this ever looked like it worked was because when both rates are very low, the noise outweighs the signal. So there’s no data for economists to really test the hypothesis on a period that matters because it’s similar to the current period of generally rising prices. But if economists just spoke to landlords, they would understand.

That’s what I did, and the reason that in 2023 I switched my model from a top-down to a bottom-up (which is the dotted line in the first chart above…and that was not revised significantly). If costs are growing for landlords, they aren’t going to be cutting rents for their tenants even if they want to cut them for new tenants to fill a unit.

It should not be a surprise that the ‘faster’ NTRR has large error bars and large revisions. Essentially, the idea behind those indices is that they take the same rent data the BLS generates and squeeze out several different indices, some of which are “faster.” But basic information theory says you can’t get 3 bits of data from a pile that holds 1 bit, for free.

What happens is that those new indices are faster…but they have huge error bars that are huger the shorter the forecast length. Duh. Which means you can’t reject any null hypothesis about the near-term path. In the original paper they mention this, and they show the data on the variance, but they didn’t really explain it well. The short way to describe the problem is that you can’t get three pounds of crap out of a one-pound bag. Period.

Now…having said all that, I do entertain the possibility that rents could slow meaningfully further than here, even more than the mild softening that my model has. But my reasons for that are different:

- Rents in NYC will likely decline sharply if Mamdani wins, partly because jobs will absolutely flee the city but mainly because of his not-very-veiled threat to seize property if they don’t. The smart landlords will dump their property at any price and get out, but some will try to ride out their term as Mayor. That’s unlikely to work, but they’ll try. And NYC is a big part of the rent indices (by the way, one hedge for this is to sell the Shiller NYC property index, which futures trade (thinly, but they trade) on the CME. Combined with naturally slowing rent growth from some of the really hot but now getting overbuilt areas – like Miami – and you could get the overall indices to look better than the median would.

- (Offsetting this, but probably nearer-term, LA rents will be buoyant for a while and maybe more sharply once the wildfires are further in the rear-view mirror, so the claims of “profiteering” can be ignored. They bounced right after the fires destroyed a huge number of units, but predictably, people screamed at the landlord, so that stopped. But supply and demand, you know. There are fewer rental units in Los Angeles, and rents are going to go up faster as a result.

- If mass deportations really do turn into mass deportations, then what we are already seeing with Lodging Away from Home could become broader pressure on rents. The hotels were where the newest and biggest wave of illegal migrants were housed in the big cities. Elsewhere, they live in apartments and sometimes own homes when they have been here for a while. I can’t imagine the government will be able to deport more than, say, 1mm over the next year or two. That would be 2000-4000 per work day, and while the illegal immigrants generally walked in, they generally have to be flown out. However, 1mm is still a big number, and if enough other illegal ‘self-deported’ so that you’re talking about a million households, then you’d have to consider a good chance of significant housing disinflation as the stock of rental units – currently just barely out of shortage – becomes a glut from the demand side.

But note that neither 1 nor 2 is currently something that you’d be able to detect with NTRR or Zillow (NASDAQ:ZG) or other rental indices. Maybe at the margin, we could see deportations affecting rents in some of the ‘sanctuary cities’ where a lot of the deportations are concentrated, but I doubt it. Too soon.

In any event, my forecast for rents is not super-aggressive, and I recognize there are mostly downside risks associated with those enumerated reasons. But right now? In the data? There is nothing that looks like it spells housing deflation.