FOMC minutes; Delta, PepsiCo to report; gold retreats - what’s moving markets

This article explores five of the most famous financial bubbles in history. As capital floods into the technology sector, one question lingers: Could AI be the next bubble?

The so-called "Magnificent 7" had a historically poor start to the year, all members posting double-digit losses. The S&P 500 recorded its weakest quarterly performance since the third quarter of 2022. Yet, the sell-off was concentrated: 7 out of the 11 S&P 500 sectors remained positive YTD, suggesting this was particularly an AI and technology correction.

It always starts the same way: a spark of excitement, a new opportunity, a promise of untold riches. Prices begin to climb. Sceptics are dismissed. Fortunes are made — until they’re lost. Because every bubble eventually bursts. And when it does, the fallout can ripple through entire economies. Also called an economic or asset bubble, a financial bubble occurs when the price of an asset, be it stocks, real estate, or even tulip bulbs, rises far above its intrinsic value.

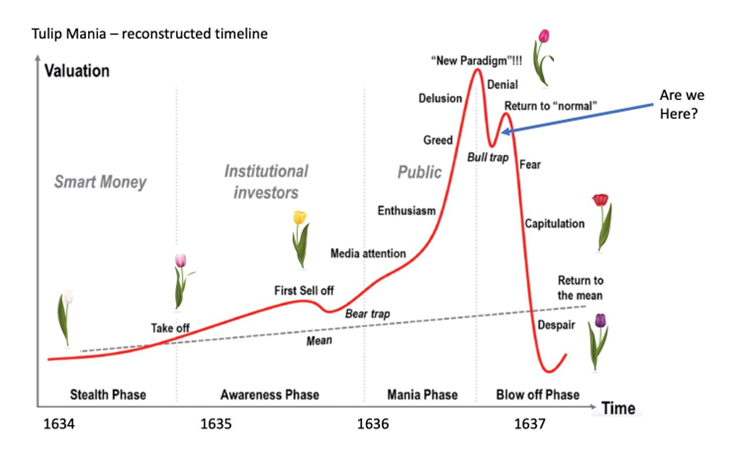

1. The Tulipmania Bubble (Netherlands, 1637)

Considered to be the first recorded financial bubble, Tulipmania hit the Dutch Republic in the early 17th century, during a period of extraordinary economic prosperity known as the Dutch Golden Age. Tulips, introduced to Europe from the Ottoman Empire, quickly became luxury items, especially rare varieties known as “broken tulips,” which displayed unique and vivid colours and patterns due to a mosaic virus.

By the 1630s, demand soared, and a futures market emerged where bulbs were bought and sold before they were even grown. Prices skyrocketed to absurd levels; some bulbs sold for more than a house in Amsterdam.

This mania was fuelled by several factors. First, during the early 17th century, the Dutch Republic experienced remarkable economic growth due to trade. By the 1630s, it ranked among the wealthiest nations, with a GDP per capita estimated at 1,200 guilders. This increased wealth during the Dutch Golden Age created liquidity, and many borrowed or diverted funds into tulip speculation.

People started buying bulbs not to plant, but to resell at a profit. Even the middle class entered the market in fear of missing out.

But in February 1637, the illusion shattered. An auction failed to attract buyers and triggered a collapse in confidence. Within days, prices nosedived. Many bulbs lost over 90% of their value.

Source: Barrie Wilkinson on LinkedIn

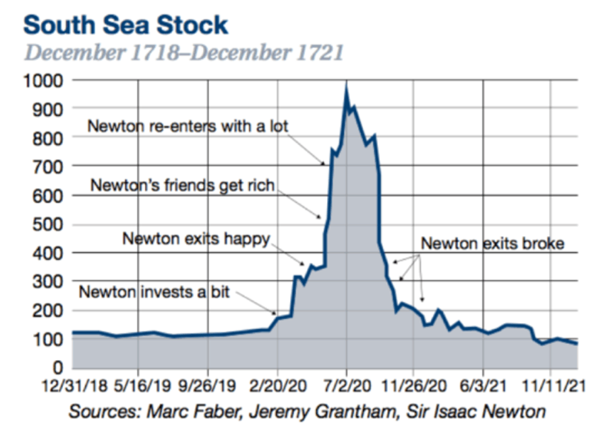

2. The South Sea Bubble (United Kingdom (TADAWUL:4280), 1720)

It is reported that Sir Isaac Newton, one of the greatest minds of the Enlightenment, lost £20,000 or the equivalent of $3 million today in the "South Sea bubble", also referred to as the world’s first Ponzi scheme. Founded in 1711, the South Sea Company was a joint public-private venture established through an Act of Parliament.

Its purpose was to develop lucrative trade with Spanish colonies in South America. The British government granted the company exclusive trading rights in the region, a monopoly that, in theory, would bring immense profits.

Inspired by the success of the East India Company, investors rushed to buy shares. The hype reached such heights that even King George I took on the role of company governor in 1718. In 1720, Parliament allowed the company to assume control of the soaring national debt, £32 million worth at a heavily discounted price.

The scheme was to fund the interest payments on the debt with capital raised from selling ever-more-expensive shares. As a result, that same year, the stock price soared from £125 in January to over £1,000 by August.

Sadly enough, the promised trade routes and riches from the South Seas, present-day South America, never materialised. The company’s success was built almost entirely on speculation, with no underlying revenues to support its skyrocketing valuation. By September 1720, confidence crumbled, and the bubble burst. Shares collapsed to £124 by year-end, triggering a financial panic across Britain.

Source: Seeking Alpha

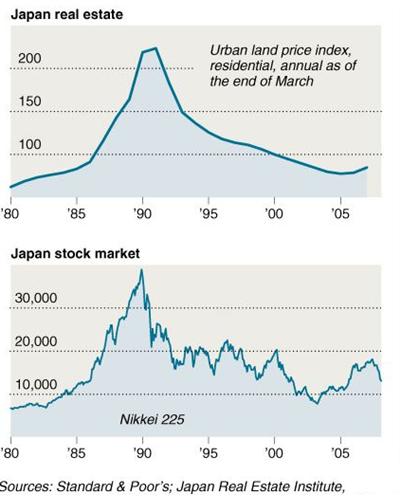

3. Japan’s Real Estate and Equity Market Bubble (Japan, 1991)

Japan’s asset bubble of the 1980s serves as a textbook example of how aggressive monetary easing can unintentionally create financial instability. In the early 1980s, a sharp appreciation of the yen, rising over 50%, plunged Japan into a recession by 1986. In response, the government implemented a mix of fiscal expansion and loose monetary policy to stimulate the economy.

These interventions proved too effective. Low interest rates and abundant liquidity ignited a speculative frenzy, particularly in equities and real estate. Between 1985 and 1989, the Nikkei stock index and urban land prices both more than tripled.

Unfortunately, the growth was unsustainable. In 1991, asset prices collapsed, banks were left with mountains of bad debt, and the country fell into a prolonged period of deflation, weak consumer demand, and sluggish growth. This period, which extended well beyond a decade, came to be known as Japan’s “Lost Decade”.

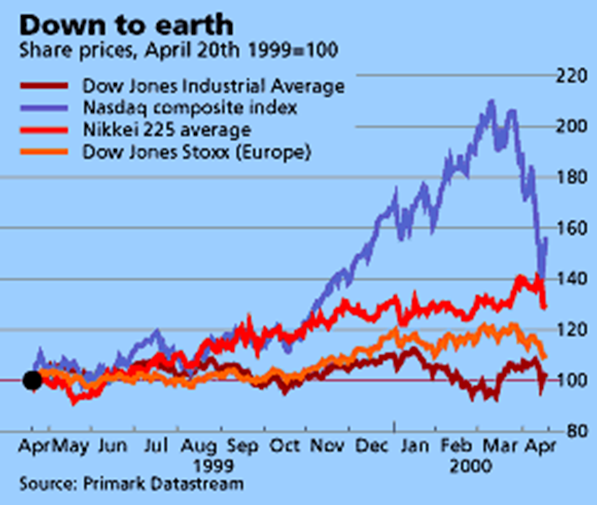

4. The Dot-com Bubble (US, 1997-2001)

Fuelled by the explosive growth of the Internet and the widespread belief in a “new economy,” investors in the late 1990s poured capital into technology and internet-based startups. The Dot-com bubble’s origins trace back to the invention of the World Wide Web in 1989 and the rapid proliferation of internet use throughout the 1990s.

Investors poured capital into technology and internet-based startups, thanks to the explosive growth of the internet and the widespread belief in a “new economy.”

The Nasdaq Composite Index skyrocketed by over 580% between 1990 and its peak in March 2000. However, many tech companies were wildly overvalued, and most startups struggled to demonstrate viable business models — particularly when it came to generating cash flow.

Confidence faltered in 2000, and the correction was brutal. The Nasdaq lost nearly 80% of its value by October 2002. Several technology and communications companies went bankrupt and into liquidation, notably Pets.co., Webvan, Boo.com, Worldcom, and NorthPoint Communications.

Yet, other internet-based companies survived including Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN), eBay (NASDAQ:EBAY), Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT), and Qualcomm (NASDAQ:QCOM), and shaped the internet age that followed.

Source: The Economist

5. The US Housing Bubble (US, 2007-2009)

In the aftermath of the dot-com bubble, capital began flowing from tech stocks towards what seemed like a more stable and tangible asset class: real estate. Simultaneously, the US Federal Reserve cut interest rates to prevent the economy from a mild recession and to mitigate uncertainty following the September 11 attacks. This low-rate environment, combined with government policies promoting homeownership, created fertile ground for one of the most consequential bubbles in modern history.

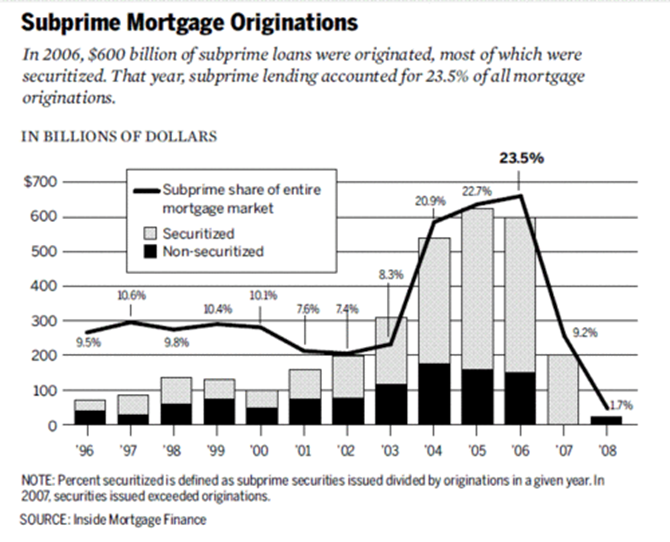

Housing demand surged as borrowing costs fell. Banks, eager to expand mortgage issuance, began relaxing lending requirements. Subprime loans, mortgages extended to borrowers with poor credit histories, became increasingly common. These high-risk mortgages were bundled into complex financial products like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) then sold to institutional investors worldwide.

As long as home prices kept rising, the risks seemed contained. Indeed, from 2000 to 2007, the median US home price rose by over 55%.

When borrowers began defaulting, especially on subprime loans, the entire system began to unravel. Banks holding toxic mortgage assets suffered catastrophic losses, credit markets froze, and the housing crash triggered the 2008 global financial crisis.

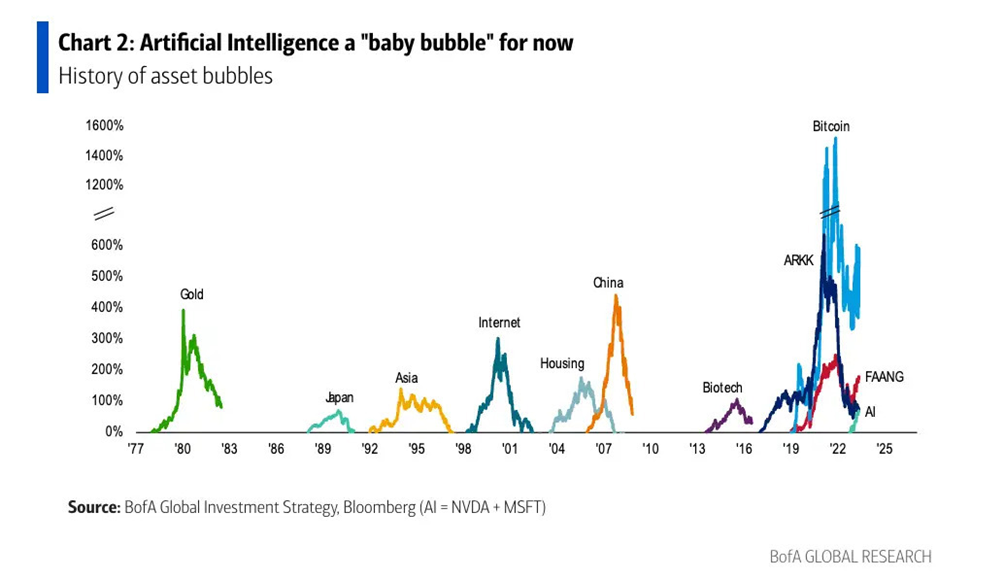

6. AI Bubble (World, 2025)?

In the first quarter of the year, tech stocks came under pressure, weighed down by macroeconomic uncertainty and tariff tensions. The Nasdaq-100 fell by -8.1%, while the S&P 500 dropped -4.3%, its weakest quarterly performance since Q3 2022. The so-called "Magnificent 7" had a historically poor start to the year as well, with all members posting double-digit losses.

However, the sell-off was largely concentrated. Seven out of the eleven sectors in the S&P 500 remained positive year-to-date, indicating that this was primarily a correction focused on technology and AI-related stocks.

Tech giants are spending billions to scale up their AI capabilities, investing in data centre infrastructure and research and development. For instance, the Stargate Project, launched under President Trump, aims to position the US as a global AI infrastructure leader, with approximately $500 billion investment over four years.

In Europe, the EU has introduced InvestAI, a €200 billion initiative for the AI sector, including €20 billion dedicated to AI gigafactories. The UAE has also partnered with France to invest between €30 and €50 billion in an AI campus and a 1-gigawatt data centre.

Still, recent events have shaken investor confidence. The DeepSeek controversy in January and the underwhelming IPO of CoreWeave, despite strong backing from Nvidia (NASDAQ:NVDA), have raised doubts about the sustainability of Big Tech’s valuations. Wall Street is increasingly questioning the narrative of “US tech exceptionalism.”

Even industry insiders are sounding alarms. Alibaba (NYSE:BABA) Chairman Joe Tsai recently warned that “the beginning of some kind of bubble” is forming around data centre construction. Microsoft, meanwhile, has reportedly cancelled several data centre projects.

Adding to the uncertainty, macroeconomic headwinds are mounting. A softening labour market, persistent inflation, and cautious consumer sentiment are eroding the post-2020 growth buffer. Economists are now warning of higher recession risks. JPMorgan recently raised its probability of a US recession from 40% to 60%.

The present hype for all things AI, particularly in today’s unstable macroeconomic and geopolitical context, certainly brings to mind some of the speculative euphoria of the past. Yet, it’s worth remembering that despite the excesses of the dot-com bubble, network technologies eventually reshaped the global economy.

The crash occurred partly because widespread adoption of the internet took longer than investors had anticipated. Similarly, progress in fields like artificial intelligence may unfold over a longer timeline, but uncertainty about timing shouldn’t be mistaken for doubt about its potential.

Source: BofA Global Research

Conclusion

The painful lessons of past financial bubbles have made one thing clear: bubbles are fuelled less by innovation and more by human emotion. The brightest minds, including figures like Isaac Newton, have fallen victim to the same cycle of greed and fear. Despite these risks, investing in equity markets has become almost necessary for those seeking inflation-beating returns. The challenge lies in not losing sight of fundamentals