Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly slide after Trump comments on weight loss drug pricing

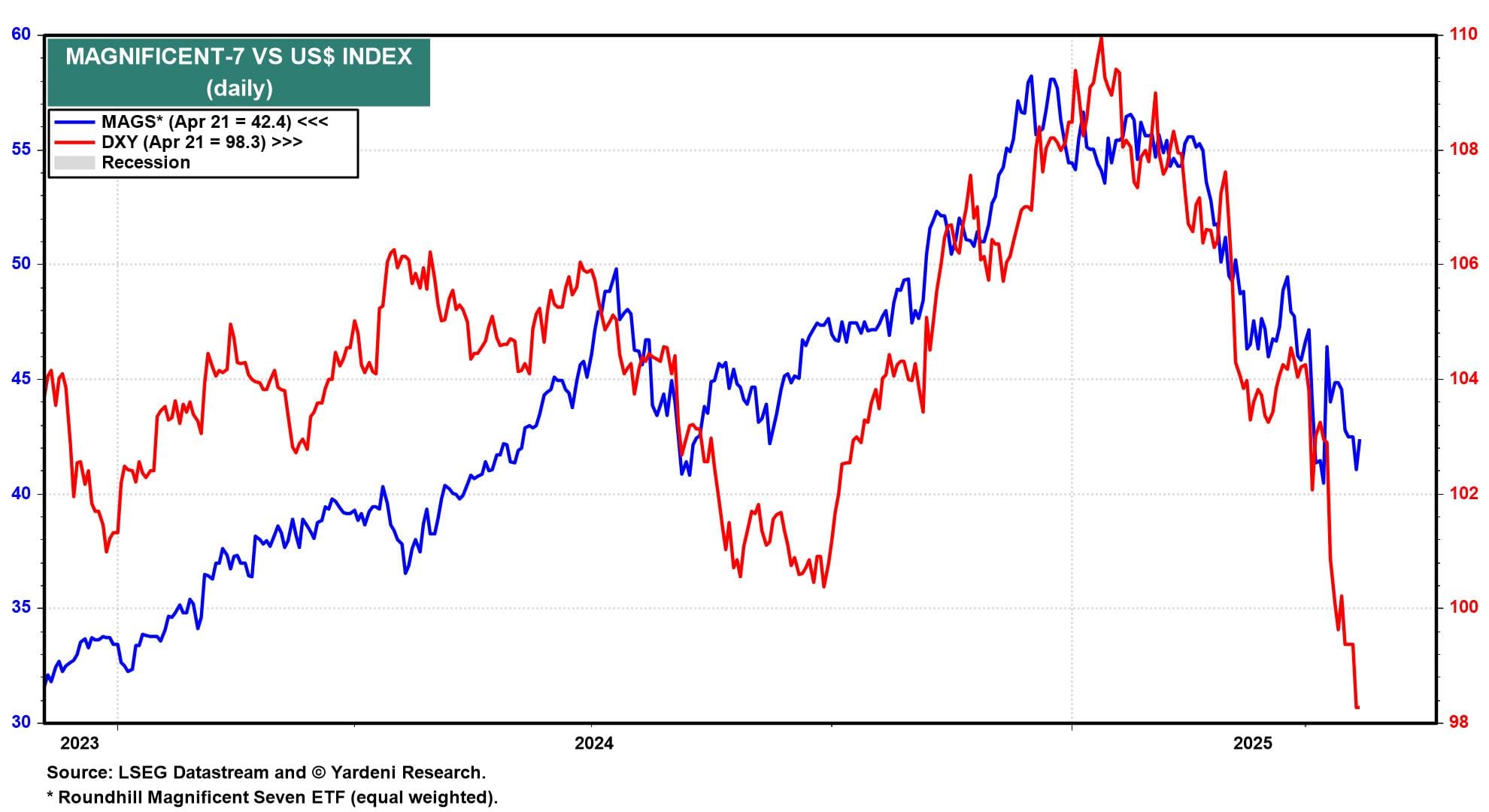

The US Dollar Index (DXY) is down 8.8% since the start of this year (chart). That has sparked lots of angst, the worry being that this might be just the beginning of a secular decline in the dollar because the US seems to be on course to decouple from the global trading system and become more self-sufficient.

If Washington’s policies reduce America’s trade deficit, there will be fewer dollars for foreigners to invest. That could cause bond yields to soar in the US, possibly triggering a debt crisis if nothing is done to narrow the federal government’s budget deficits. In this narrative, the US dollar will increasingly lose its reserve currency status.

The US is just the latest in a string of historic empires that have seen their currencies fall along with their global power.

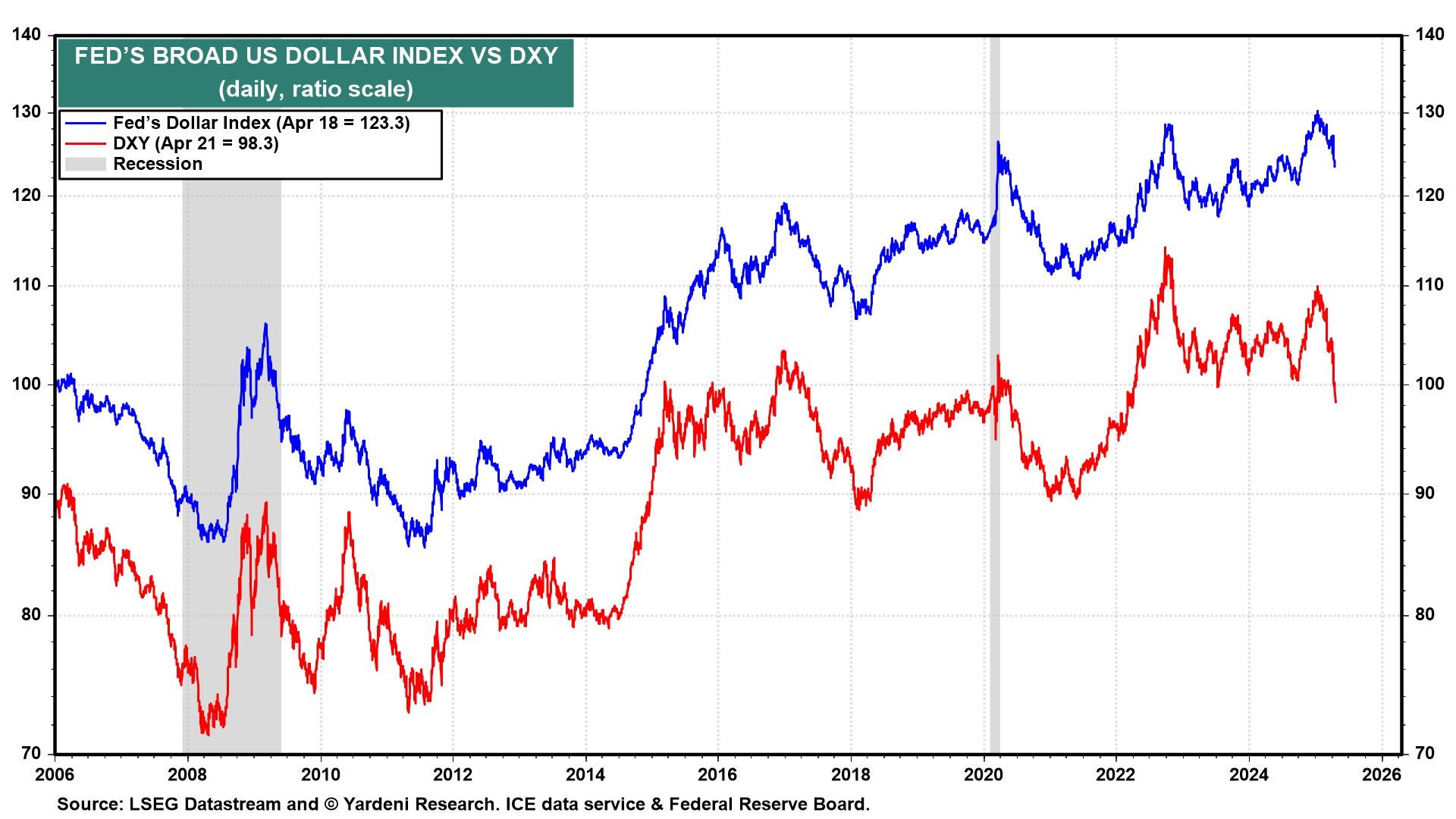

Sorry, we aren’t buying the latest eulogy for the United States and its currency. DXY remains on an upward trend that started around 2010, when it became increasingly obvious that the US recovered from the Great Financial Crisis better than the other major economies and financial systems (chart). The US capital markets remain the biggest and most liquid in the world. That’s not going to change anytime soon.

The recent weakness in the dollar is mostly attributable to the selloff in the Magnificent-7 stocks, in our opinion (chart).

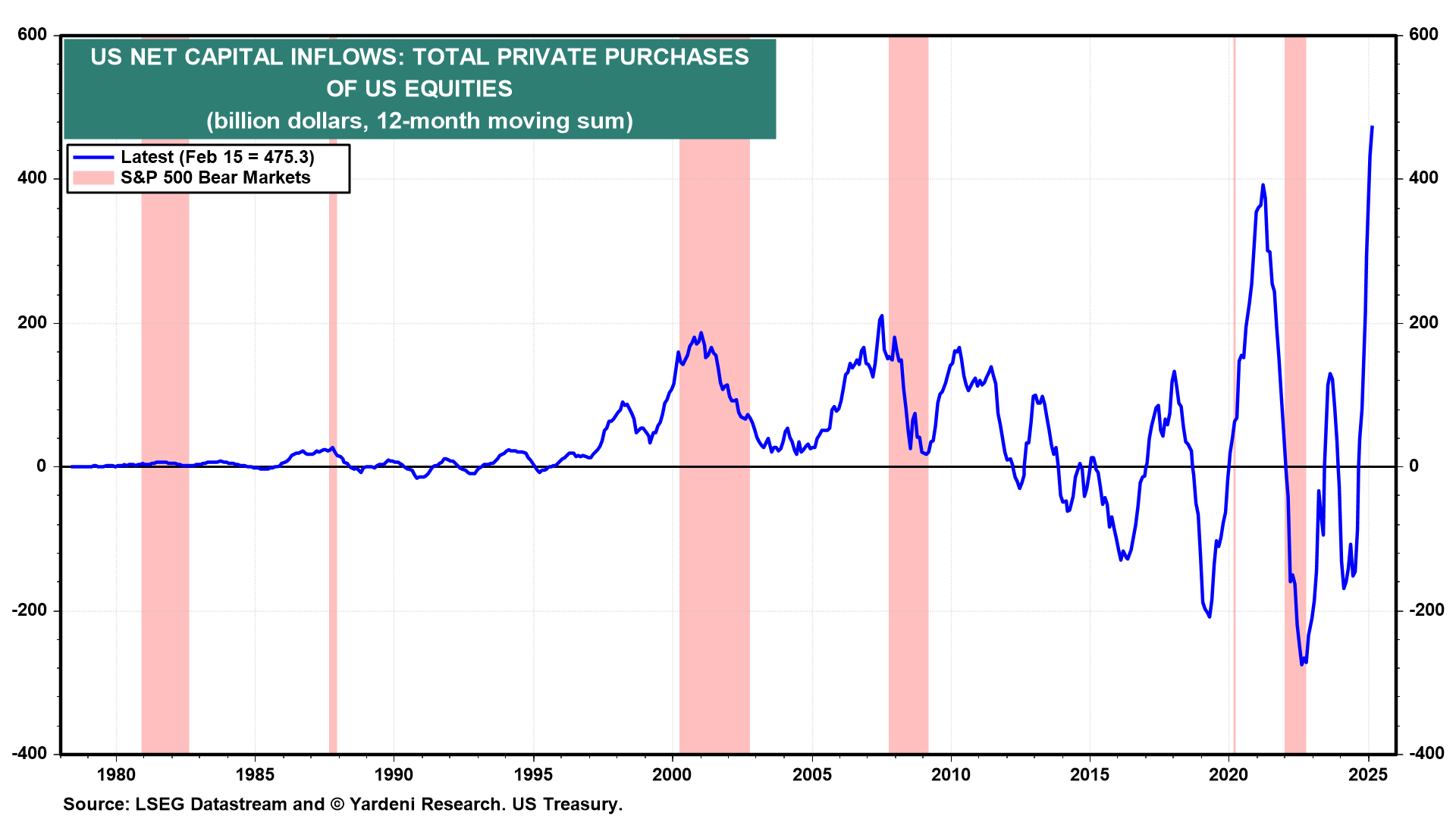

Foreign investors ploughed a record $475.3 billion into the US stock market over the 12 months through February (chart). Undoubtedly, lots of those funds were spent on the Magnificent-7 at their record valuation multiples at the start of this year. Trump’s Tariff Turmoil unnerved foreign investors (along with domestic investors). As a result, foreigners reversed course and bailed out of US stocks, especially the Magnificent-7.

European investors, along with other investors around the world, piled into European stocks because they were much cheaper than the Magnificent-7. So the euro rose sharply, which drove DXY lower (chart). The euro has a disproportionate influence on DXY.

The Fed compiles an alternative trade-weighted US dollar index that is broader than the DXY. It is down by about half as much as DXY since the start of this year (chart). It is showing a steeper upward trend than DXY since 2010.

The Fed disaggregates its broad dollar index to show the foreign exchange value of the dollar relative to the currencies of advanced economies and emerging market ones (chart). The dollar has been mostly moving sideways relative to the former for the past couple of years, while soaring to new highs relative to the latter.

We conclude that the recent weakness in DXY mostly reflects the strength in the euro, which we don’t think is sustainable. A strong euro could very well push the Eurozone into a recession, forcing the European Central Bank to continue lowering interest rates while the Fed remains slow to do the same.